It’s no great leap for a songwriter to pen a tune about being in love. Most of them probably have been.

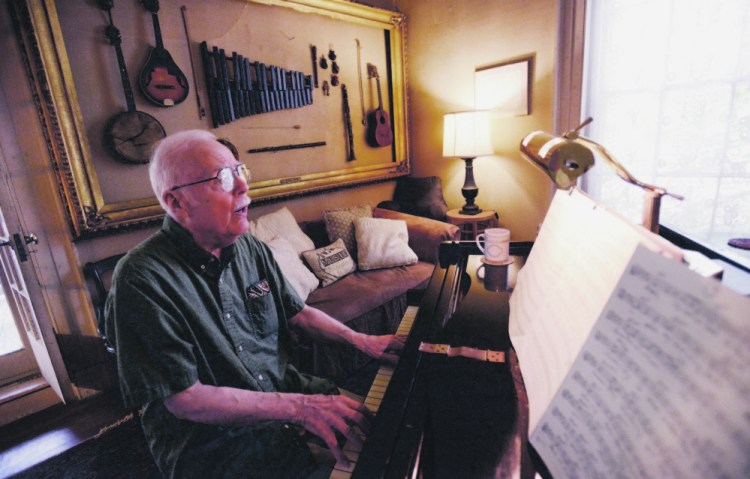

But Hank Beebe, who has written songs for musical theater for some 60 years, is extremely proud of a song he wrote from the perspective of a diesel engine.

“We Were There” is a snappy, breezy tune recounting all the wondrous technical achievements diesel engines have been part of, from building great canals or draining swamps to helping man settle uncharted parts of the world. Beebe wrote it with his longtime partner, lyricist Bill Heyer, for the 1966 musical “Diesel Dazzle,” starring Hal Linden and David Hartman.

Don’t know the show? You shouldn’t. “Diesel Dazzle” was an industrial musical, one of hundreds of shows created with Broadway-caliber talent but performed exclusively for salesmen and executives at giant corporations like General Motors, General Electric and American-Standard (makers of toilets). The general public didn’t see them, they weren’t made into films and no records of the music was sold. But companies spent millions on them, from the 1950s into the 1980s, convinced that the power of song was motivating their employees and making their company more profitable.

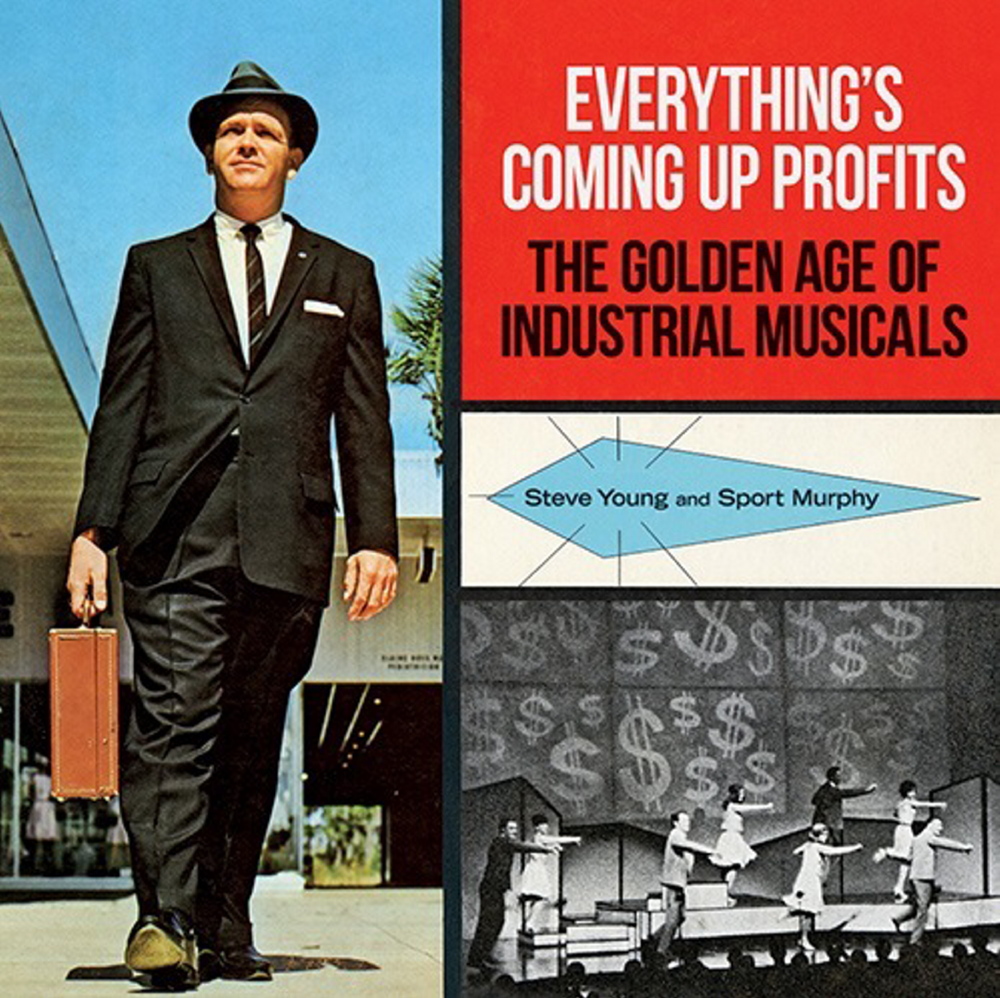

Beebe, 89, will be doing his part to explain the industrial musical phenomenon when he appears at Space Gallery in Portland on Saturday. The Portland resident will be part of a show called “Industrial Musicals” featuring films and oral history. The show will be hosted by Steve Young, co-author of the book “Everything’s Coming Up Profits: The Golden Age of Industrial Musicals,” with Sport Murphy.

Young will explain the history of the genre and show film clips of numbers written for shows put on by Citgo, Purina, Hamm’s beer and others. He’ll show a film version of American-Standard’s 1969 show “The Bathrooms Are Coming,” as well as a film used as part of the 1973 General Electric show “Got to Investigate Silicones,” written by Beebe and Heyer. That show features a bouncy song called “The Answer,” explaining all the problems silicones can be the answer to.

During his long career as a composer, Beebe’s resume includes a revival of the Broadway show “Hellzapoppin'” with Jerry Lewis and Lynn Redgrave in 1976, and an off-Broadway hit in 1975 called “Tuscaloosa’s Calling Me, But I’m Not Going.” The latter won the Outer Critics Award for Best Off-Broadway Musical.

Though he didn’t get his name in lights for his industrial musicals, he made a living and worked at something he loved for a long time. And he loved the challenges the jobs presented.

“That song (‘We Were There’) was one of the most difficult songs we had to write, because (the diesel engine) has no glamour. A car has glamour and style. Even a bathroom has some style,” said Beebe, a New Jersey native. “It’s easier to write about love.”

Young, a long-time writer for “Late Show with David Letterman,” began making the world aware of industrial musicals as a joke. He was in charge of a recurring skit called “Dave’s Record Collection.” His job was to find silly, weird recordings for Letterman to talk about.

Albums from industrial musicals were made and given to employees or the people involved in the shows. So they do exist but are rare. Young found one from a 1960s show for General Electric called “Go Fly a Kite,” all about Ben Franklin and electricity. The show was written by John Kander and Fred Ebb, who went on to write such Broadway hits as “Cabaret” and “Chicago.”

Finding that record made Young, a Massachusetts native, curious about the genre. He scoured used record stores and found more, including several written by Beebe and Heyer.

The songs Young found were about weird topics – bathrooms or silicones – but were well-crafted, smart and catchy. After years of research, Young has concluded that Beebe and Heyer were among the best composer-lyricist teams to work on industrial musicals.

“I consider them to be the (John) Lennon and (Paul) McCartney of the genre. They did great work under nearly impossible parameters,” said Young, 49, from his home in New York City.

Young started calling people who worked on industrial musicals, including Beebe. He also talked to Hal Linden, who was in several and later became famous on TV for playing a funny New York detective on “Barney Miller” in the 1970s. Young worked on research for years before publishing his book about two years ago.

Though industrials had their heyday in the 1950s through the ’80s, Young says he found more recent examples, including a show Walmart put on about 10 years ago.

In the years of research for his book, Young turned up tidbits like this: “My Fair Lady” opened on Broadway in the mid-’50s with a budget of about $500,000, around the same time that Chevrolet put on a touring show about its new cars with a budget of about $3 million.

The money spent on industrial musicals is a testament to the economic might of American companies in the baby boom era, Young said.

But companies weren’t throwing away money, Beebe said. They were spending money to harness the power of music. They made musicals to motivate workers, especially salespeople, and found that the musicals directly improved sales.

“If they hadn’t been effective, they wouldn’t have lasted three decades,” said Beebe. “Seeing the new products revealed to them with singing and dancing and fireworks made (the salespeople) more enthusiastic, and enthusiasm is what you need to sell.”

Beebe applied a workman-like ethic to writing songs for salesmen. He and Heyer would get a job to write a show, say for McDonald’s, then travel the country talking to workers at all levels.

Then they’d try to write music those people could relate to.

A MUSIC MAN FROM THE START

Beebe grew up in Pitman, New Jersey, near Philadelphia. He remembers being about 4 years old when an uncle sat him at a piano and taught him to play a 1930s hit called “Penthouse Serenade” with two fingers. That moment triggered a life’s passion for music, fueled by a family of singers and music teachers.

When he came back from service in World War II, near the end of the war and in this country, he earned a master’s degree in musical composition from the University of North Carolina.

He moved to New York City. In the early ’50s, he was doing a nightclub act there with his brother-in-law when his agent called and told him he had booked an audition for “the Chevy show.”

At the time, singer Dinah Shore had a TV show sponsored by Chevrolet, and Beebe thought that was the gig. It wasn’t. The gig was writing a musical about the new Chevy cars coming out for 1957.

That show opened at a 5,000-seat theater in Detroit, he said. There was no marquee with the show’s name, or Beebe’s name, for that matter. Just a sign that said “Welcome Dealers.”

Beebe quickly established a reputation for being able to write catchy tunes about anything companies wanted to sell, and he worked steadily in the genre into the 1980s. He and his wife moved to Maine after living for many years in New York. They came to live in Portland after visiting a friend who had a home in Freeport and falling in love with the area.

Beebe said he and Heyer would research a product and talk to employees, and also talk to the company “brass” to find out about their goals for the musical. Then they’d write half a show, including maybe three songs and a couple comedy sketches. Then they’d wheel a piano into some corporate board room, and play what they had for the executives.

Beebe said he always thought of his industrial musicals as “disposable work,” so he’s happy that Young has discovered the genre and is sharing it with others. Young is also creating a documentary film about industrial musicals, and he filmed an interview with Beebe at Beebe’s Portland home in April.

“Hank has a wonderful attitude about what he did, writing those musicals. He never looked at it as crass,” said Young. “He looked it at as something he could do to help someone, the guy selling cars. And his work was great.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.