Susie Kiehn-Geary, head server at the Miss Portland Diner, dropped off a check at the table where Mary Keaney and Bev McGillicuddy were enjoying their regular afternoon repast of toast, an English muffin and coffee.

McGillicuddy’s check came to $7.83, and she left a $4 tip. That’s about 50 percent, well above the standard 15 or 20 percent tip left by most diners. And, she says, that’s not likely to change, even if Kiehn-Geary’s base wage goes up to $6.35 or $11.25 – figures that are part of separate proposals for a minimum wage increase in the city.

McGillicuddy eats out several times a week and has gotten friendly with her servers. Her tipping habits, and those of other diners in Portland who said they wouldn’t be dissuaded by higher waitstaff wages, are in line with research that has found that people’s behavior in tipping has as much to do with their own interest in being – or appearing – generous as it does with the quality of service or servers’ financial need.

“I tip probably more than people think I should,” said McGillicuddy, who lives in Gorham and works as a lunch aide at Dyer Elementary School in South Portland. “But I have a relationship with all these people. Most of them are going to school or just starting out, and they have bills like we do.”

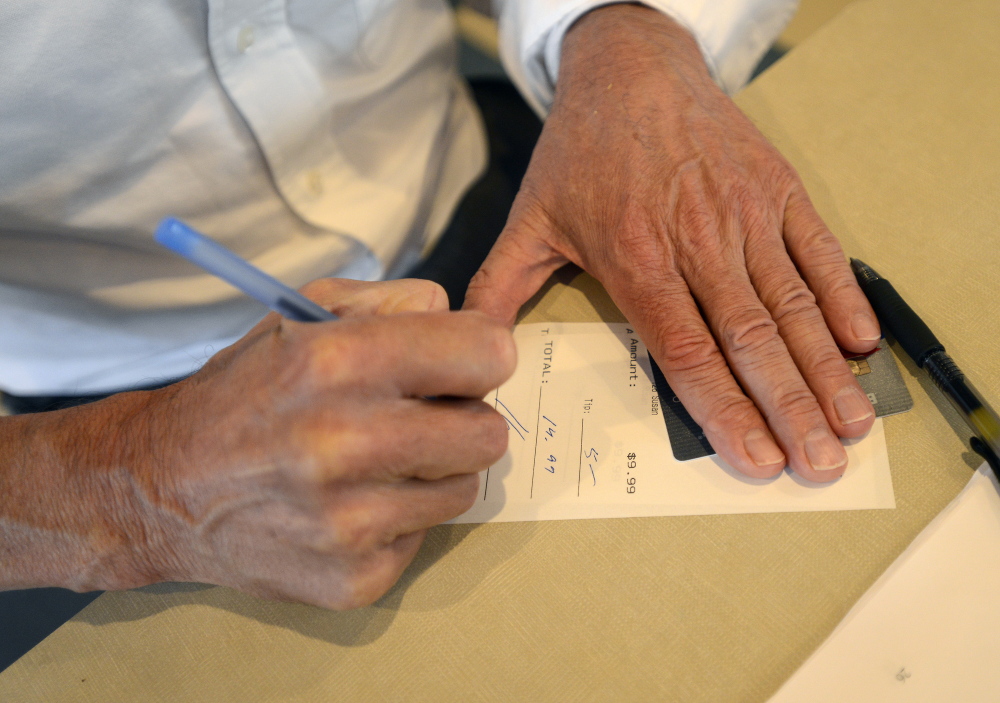

Servers also get a healthy serving of empathy from customers like Kaighn Smith, an attorney who works at a law firm down the street from the diner. Smith once waited tables himself, and his daughter has worked in a restaurant, so he knows how tough the job can be. (He left a $5 tip on his $9.99 bill.)

“I think these restaurant workers work very hard and they deserve every penny that they earn,” Smith said. “The minimum wage is still the minimum wage.”

While people tend to think that they tip to reward good service, research shows that tipping is actually a psychological game heavily influenced by social pressures and personal interactions between the diner and the server. If diners are told their servers are suddenly going to be making twice their base pay, then yes, some people will tip less. But many others will not, says Michael Lynn, a professor of consumer behavior and marketing at the Cornell University School of Hotel Administration who has researched the psychology of tipping and put himself through school waiting tables.

Not much research has been done on how changes in the minimum wage affect tipping, Lynn said. States that have a higher tipped minimum wage do seem to see “slightly lower” tip percentages in the months that follow. But even when people tip less, he added, “it’s not a huge difference, and everybody is tipping above 15 percent.”

“Certainly if you talk to consumers and tell them your server is soon going to be making 15 bucks an hour, you’re going to have consumers who say, ‘Well, under those circumstances I’m going to tip less,’ ” he said. “Not everybody says that, but people do say that. Will they actually tip less? Yes, some of them. But many of them who think they’ll tip less, won’t.”

Ofer Azar, a researcher who has studied the economics of tipping, says some customers may well stop tipping if restaurants impose a service charge similar to the gratuities added to a bill for large groups, leaving some servers worse off than before. People tend to view a service charge as a substitute for a tip.

But, Azar said, “I think tipping is a strong social norm, and it won’t shift significantly so quickly, even if the minimum wage is changed. But maybe a little bit.”

‘IT’S MORE ABOUT THE SERVICE’

About 40 percent of workers earning minimum wage in Portland are tipped workers, according to the Maine Department of Labor.

Shannon Tallman, a Portland resident who dines out at least once a week with her wife, says she almost always tips 20 percent to 25 percent and will continue to do so if the tipped minimum wage changes. “For me, it’s more about the service than what they’re making an hour,” she said.

Lynn has closely followed the story of Ivar’s, a Seattle restaurant that last spring raised its employees’ base pay to $15 in advance of the city’s phased-in minimum wage increase. The restaurant raised menu prices and told customers they could stop tipping. Lynn predicted that, over the long term, diners would start tipping anyway.

“In subsequent conversations I’ve had with (the owner), he indicated that the biggest complaint they got from customers was that they removed the tip spot from charge slips,” Lynn said. “He didn’t want to put any pressure on people to tip. He wanted it to be a no-tipping place. But people wanted that opportunity to tip. When he finally relented and put it back, he said about half of his customers are already tipping.”

The tips aren’t back to the 15 percent to 20 percent range yet, but Lynn predicts they will be, eventually. Why? Once some people start tipping, it creates social pressure on everyone else to do the same.

‘THERE ARE THINGS SERVERS CAN DO’

There’s also a lot of social interactions between diner and server that determine whether or not someone will leave a tip, and how much they will leave. These factors won’t change even if Portland servers’ base wage increases.

“There are things servers can do, like squatting down next to the table, smiling at customers, touching them briefly on the arm or shoulder, writing thank you on the back of the check – those all increase tips,” Lynn said.

Lynn has gathered a list of 20 such techniques that have been found to increase the tip a diner will leave on the table. Using even a few of the techniques can lead to a 10 percent to 30 percent increase in tips, he says. Using a tip tray with a credit card insignia on it, for example, means a possible increase of at least 20 percent. No one has definitively nailed down why, Lynn said, but it’s probably a bit of “classical conditioning” that lights up the areas of the brain associated with spending money. That means it’s easier for customers to leave a larger tip.

Ever had a server say “good choice” when you order? He isn’t just being nice. He’s trying to get more money out of you by complimenting your choices.

Without knowing it, Susie Kiehn-Geary already uses many of Lynn’s techniques at the Miss Portland Diner, including one of the biggest tips for women: Put on makeup, and wear attractive clothing. The 56-year-old waitress, who has been working in the industry on and off for 40 years, keeps her blond hair pulled back and wears a spiffy blue shirt sporting the Miss Portland Diner logo.

Kiehn-Geary looks customers straight in the eye. She smiles. (“You can’t smile enough,” she said, “even if you don’t want to.”) She treats guests as her friends, peppering them with questions about where they’re from and what they’re doing in Portland, to make them feel more comfortable and let them know she cares about who they are. Research says drawing a picture on a check (such as the ubiquitous smiley face) can increase tips, and Kiehn-Geary does that, too. Around the Fourth of July, she drew little bursts of fireworks on all her customers’ checks.

“Anybody can take an order and put a plate down, fill a coffee cup,” she said. “But engaging in a relationship with that table is what works.”

Her biggest tip in her career? A plane ticket from a flirty airline pilot, she said.

Kiehn-Geary excused herself from a conversation with a reporter to go welcome a family of four who had just walked into the diner.

“Hi, folks! Have you been here before?” she said. “I have a special place for you, if you’ll follow me.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.