Falmouth painter David Driskell’s accomplishments, from the American South to South Africa, are already the stuff of history. But sometimes we confuse talking about art with talking about artists. It’s tempting in Driskell’s case: How many Americans, after all, have a dozen honorary doctoral degrees?

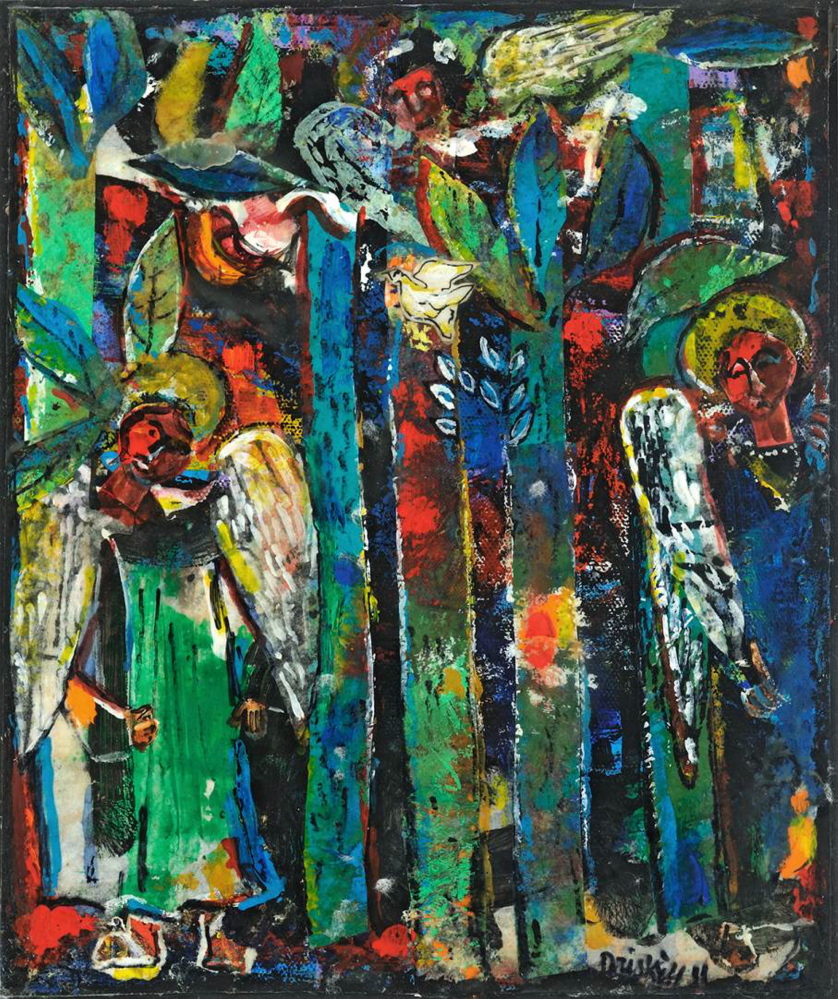

But beneath his accomplishments as an author, scholar, educator and cultural ambassador, let’s not forget the resident of Falmouth is a great painter. The new works on view in “Visual Encounters: Recent Work” are vigorous, rich and bold. While they largely follow their swirling gestural rhythms towards abstraction, the paintings tend to float like falling autumn leaves toward dense landscapes under forest (and sometimes jungle) canopies generally so full that they barely hint of sky. Driskell’s other common mode is the portrait, another type of fully frontal image – as opposed to landscapes that recede into depth via fore, mid and backgrounds. Consequently, it is easy to see Driskell’s paintings as rooted in the frontal pictorial logic of painterly modernism.

Driskell’s use of color and forms reinforces his modernist roots. They echo the lessons of Matisse, van Gogh, Derain, Braque, Klee and others who reached for the bold visual and emotional presence of painting through intense color, raw forms, dynamic composition and uncamouflaged brushwork.

Modernism can be seen as a historical movement or as a strategy for toppling current assumptions. Echoing the historical aspects of modernism is indirect and requires the viewer to think in terms of historical context, but Driskell primarily employs modernism without irony, as a direct approach for making his own paintings. For example, whereas Picasso’s cubist references to African sculpture sought to blaze trails for the possibilities of painting, Driskell’s references are far more direct and open. His encaustic and collage “Mask Lady” features an acorn-shaped African face in a dense jungle setting replete with plant forms unabashedly borrowed from Matisse. Driskell’s mask, however, is not caught in Picasso’s representational traps or exoticism. Instead, we feel free to reflect on the spiritual power of the facial form. It could channel our ancestry, our ghosts, diasporic culture, the fundamental circuitry of being human or many other things. We can see self or other in the face, but we are invited to find our own path and meaning in the work.

Driskell’s clearest artistic inspirations in “Visual Encounters,” however, are Matisse and van Gogh. Matisse is apparent in Driskell’s palette and shapes, and Matisse’s seminal portrait of his wife, “The Green Stripe,” is undoubtedly the inspiration for a color proof of Driskell’s forthcoming woodblock edition titled “Straw Hat.” What seems so simple at first comes into focus as a masterpiece of color logic as it intersects with open form: The color shifts move us left to right (red to green) while the forms – in particular, the subject’s eyes – shift from clear to open forms that then flow up toward an unusual bit of punctuation in a stoplight-like black rectangular form with three green dots, which delivers us back through the yellow of the hat only to start again on the left of the rebounding red.

The strongest images in “Visual Encounters” include the large “Night Light Pines.” The Maine pine is Driskell’s totemic anchor. This particular work looks back to Driskell’s paintings of the 1950s (or his 1971 “Pine and Moon” on display now at the Portland Museum of Art), but with an overwhelmingly fresh spirit. Moreover, it recalls van Gogh, who, despite his fame, is a rare model simply because it is too difficult for most painters to employ his bold wet stroke style without devolving into mud.

“Pines with Moon” (2014) also follows the swirling van Gogh-esque brushwork, but in a deliciously rich and limited blue and green nocturnal palette that flows seamlessly between forest and starry night sky. It is sumptuous and lively, but it is quietly indulgent. This work raises the idea of modal thinking behind the jazz trumpeter Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool.” (Driskell isn’t musically trained, but he became familiar with this way of thinking when spending time with another jazz horn player, Wynton Marsalis — major and minor are just two of the modes.) The connection is reinforced by “Night Embers,” a canvas that echoes the allover nocturnal blue palette but with a band of hot red and yellow strokes that appears like a key change in the bridge of a jazz tune.

The similarly musical notions of rhythmic density and time are brought into relief by Driskell’s smaller works on paper. While the larger works reveal arm-sized gestures of a man standing at his easel, the smaller works like “Magic Tree” exude the wrist gestures of drawing or writing flat at a table. This makes for a different mode defined by quicker rhythms (like the heartbeat of a bird) and surprising calligraphic complexity. The smaller works are both more intimate and – because of their detailed complexity – vaster than the large ones.

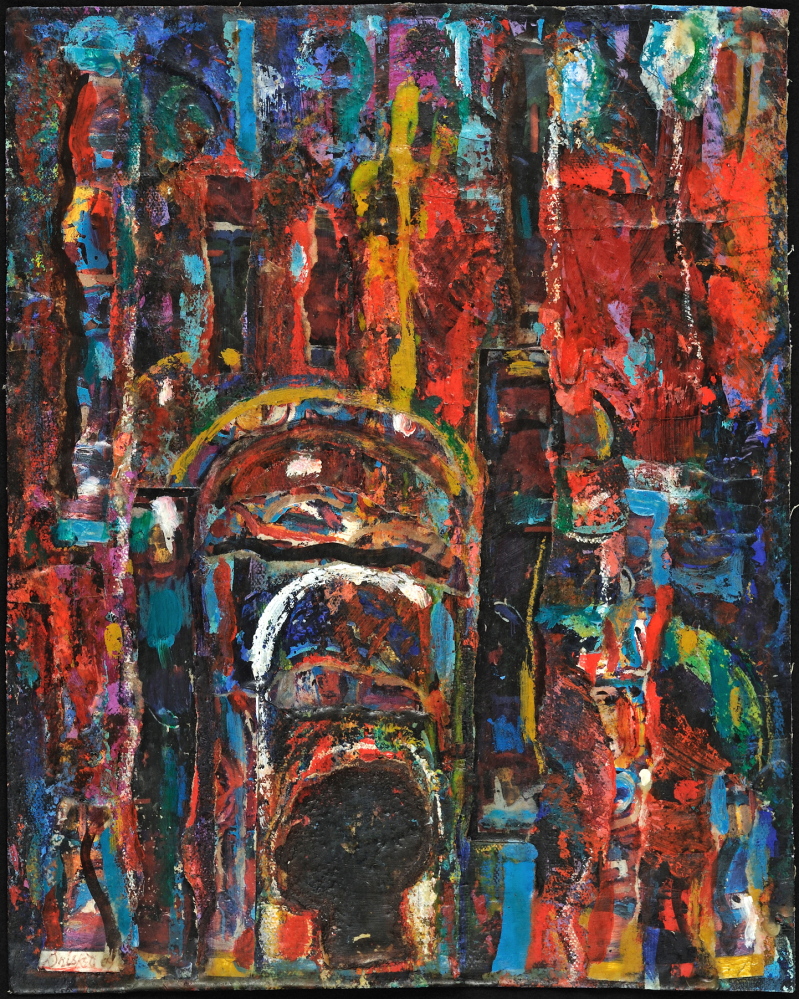

A pair of older large works serves as testament to Driskells’ gathering vigor. “Two Figures” from 1989 uses a similar stained-glass palette, but one that glows with hot reds (as opposed to the nocturnal blues). The work’s warm modal intensity is strong, but the spiritual orientation of both paintings operates more distantly than the newer works.

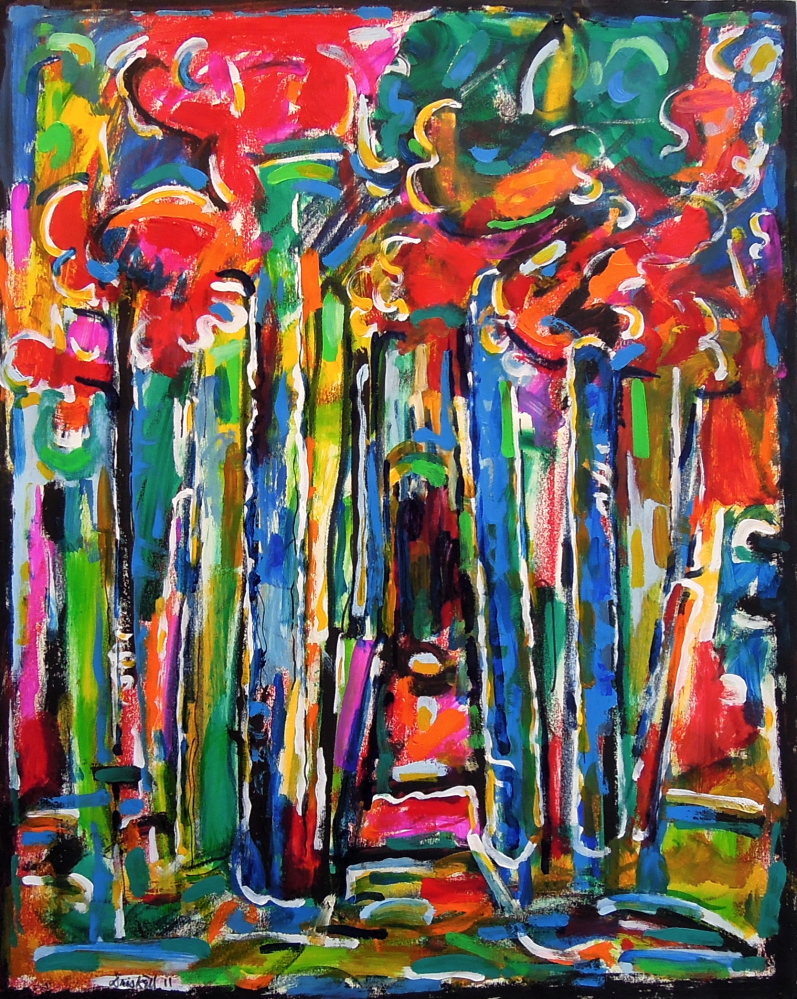

A particularly interesting formal approach to Driskell’s new paintings is best illustrated by “Movement in the Trees,” in which the pines appear as two parts: mast-like verticals that soar up the top half of the image, and curved forms that corkscrew like the outside edge of oak leaves shimmying throughout the denser bottom. This somehow both deconstructs the essential forms of a tree while creating a formalist map of a forest in compositional terms: up, down and then around and around. Driskell takes this to a wild, alternate conclusion with deciduous trees in “Autumn Forest” with a fauvist (think late Matisse or even Peter Max) palette of pinks, reds, oranges, whites, blues and chartreuse. This piece begins with the horizontal-stroked ground before riding skyrocketing trunk verticals up to the rapturously swirling forms of the canopy.

Because of their visual strength, Driskell’s paintings are accessible to anyone. While they offer paths for long looks and deep thoughts, they don’t require explanation or background.

You don’t need to know his biography to understand Driskell’s paintings. In fact, the reverse path is more helpful: The strength of his paintings helps explain Driskell’s history of great accomplishments.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.