DEBLOIS — It’s barely 7 a.m. and a sleepy 3-year-old, Madeline Ramirez, is clutching her dinosaur stuffie and waiting in line to board the yellow school bus with about a dozen kids.

Across the road stretch acres of blueberry fields, the reason these children are here and going to school on a midsummer day.

As her parents, Aurelio and Juana Ramirez from Oaxaca, Mexico, head out for a long day raking blueberries by hand, Madeline and her three siblings are boarding the bus for Blueberry Harvest School, a special three-week school in Harrington for migrant workers’ children ages 3 to 13. Before bringing their family to Maine, the Ramirezes had raked blueberries in New Jersey and Florida this year.

“I like it very much, each year my children can go and learn,” Aurelio Ramirez says. “We know our children are safe and secure while we’re working,” his wife adds.

The school is part of the state’s year-round Migrant Education Program, administered by the Maine Department of Education and fully funded with $1.1 million annually in federal funds. It serves students from other Maine counties and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and those traveling from up the “migrant eastern stream” from Texas, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi.

Although it’s a year-round program, almost 90 percent of the 1,352 migrant students served over the last 10 years were in Maine because of the blueberry harvest Down East, according to David Fisk, the state director of the program. The next biggest group of students – 83 – was in Maine during broccoli season. From there, the number of students associated with a particular crop drops off sharply. Other major crops, such as potatoes, are largely mechanized and demand for migrant labor is low, Fisk said.

Although some workers come from Mexico, Texas and Florida, most migrant workers in the blueberry barrens of Washington County are Micmac Indians from New Brunswick, some traveling with large extended families for the season – just as their parents and grandparents did.

“It’s a tradition. I came here as a child, and I brought my kids when we used to work in the blueberry fields,” said Peggy Clement, who started teaching at the school about 15 years ago and is a teacher and Head Start director in Elsipogtog, New Brunswick. “A lot of families in our community come and they depend on the school.”

Donna Augustine, a Micmac who is a community liaison for the school, said the Micmacs have always traveled to follow the hunting and fishing seasons.

“I was raking when I was 8 years old,” said Augustine, now 63. “It’s become traditional for our people.”

The school has become an important part of the experience, said Augustine, whose Micmac spirit name is Thunderbird Turtle Woman.

“It’s incredible. It’s educational and fun for the kids,” she said. “And the parents need it.”

Back on the bus, Madeline settles in a seat while her 6-year-old sister, Selena, curls up on a seat to nap, draping herself with a pink-striped fleece with just her silver glitter sneakers peeking out. Nearby two sisters play a hand-clapping game before breaking out into a rousing chorus of “Let it Go,” then dissolving into giggles.

The bus bounces down rutted, winding dirt roads through small enclaves of mobile homes tucked close together in the woods before arriving at Harrington Elementary School. Teachers line the curb, calling out, “Good morning! Buenos dias!” as they gather the students in their classrooms and take them inside for breakfast before class begins.

‘A BIG LOGISTICAL FEAT’

Putting together a school for so many students, from so many places, of all different ages and cultures, is a challenge, organizers say. The funding for the program has been steady at $1.1 million since 2002 even though the number of students served has increased over time, Fisk said. In 2009, there were 159 students served during blueberry season; in 2014, there were 329 students.

Organizers say the increase in student enrollment is likely because they are getting better at identifying eligible children and getting them involved in the school. In recent years, the blueberry industry has used fewer migrant workers as growers switch to mechanized harvest on barrens that are flat and even.

Teaching migrant students of different ages, cultures, languages and experiences in such a short period “is a big logistical feat,” said Ian Yaffe, executive director of Mano en Mano, the Milbridge-based nonprofit contracted to run the Blueberry Harvest School.

A team of more than 32 people – including cafeteria workers, a nurse, 19 teachers and community liaisons – works with the children. There are three yellow school bus routes, traveling more than 260 miles every day to pick up and drop off kids at sometimes remote camps. About 80 students a day attend the school, where they are grouped by age and taught by a mostly bilingual staff, some of whom raked blueberries themselves or attended the school as children.

In addition to identifying the eligible students and telling their families about the school, the school workers must be flexible since they don’t know how many students will show up on any given day, or what those students may need.

The school provides breakfast, lunch and snacks and weekly field trips tied to the curriculum, which is organized around weekly themes of personal identity, conservation and coastal Maine.

This past Thursday, students were going on a hike but many didn’t have proper shoes. In the cafeteria, more than a dozen children headed to the stage to sift through the piles of donated sneakers to find the right size, leaving behind their sandals and flip-flops.

Later, at Pigeon Hill in Steuben, the students hiked over a mile through the forest, stopping to read “The Lorax” in English and Spanish and discussing conservation before arriving at a clearing on top of the hill, overlooking a classic Down East vista of forest and coastline.

“We’re trying to keep the kids engaged over the summer. A lot of the kids have gaps in their education because of their moves,” said teacher Emma McCumber.

‘WE EXIST FOR THEM’

Yaffe and teachers emphasize the need to teach students wherever they are academically, in order to build on those skills, and to incorporate their diversity and experiences into the coursework.

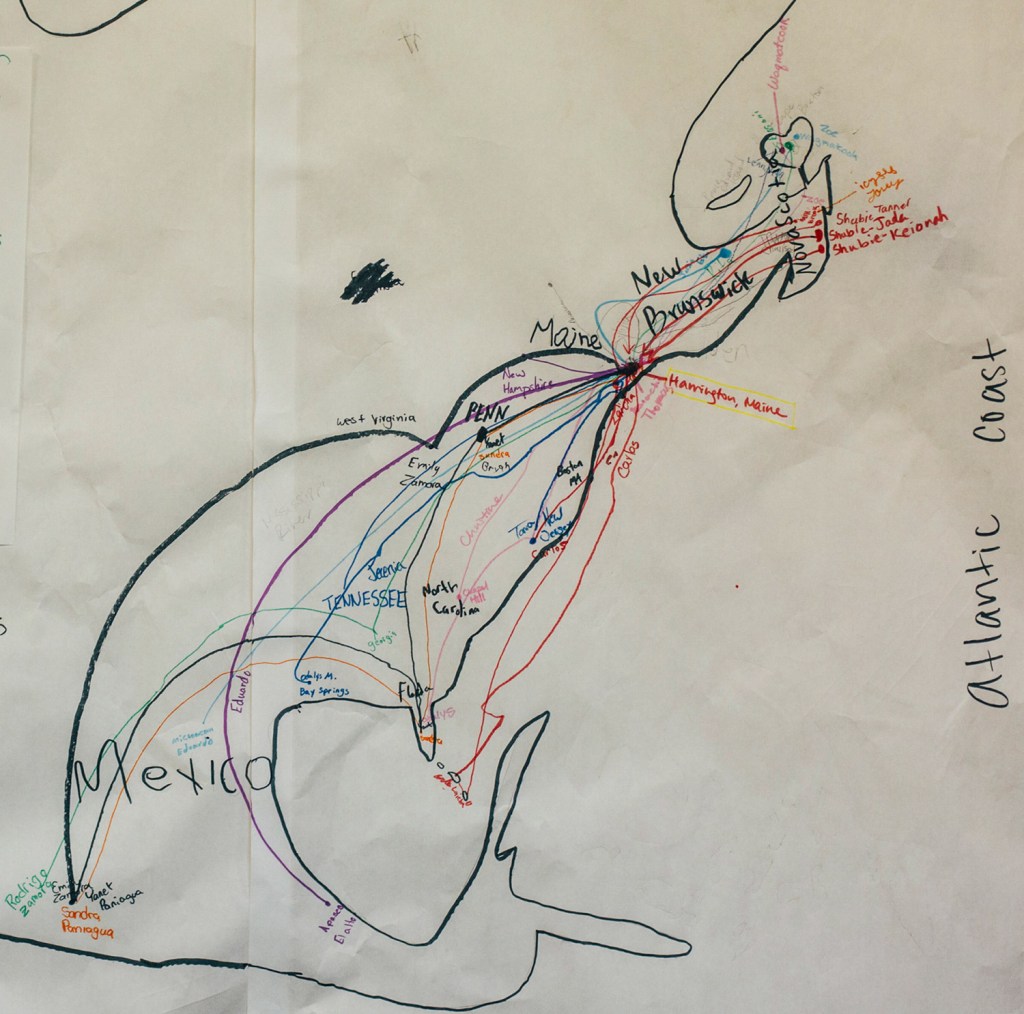

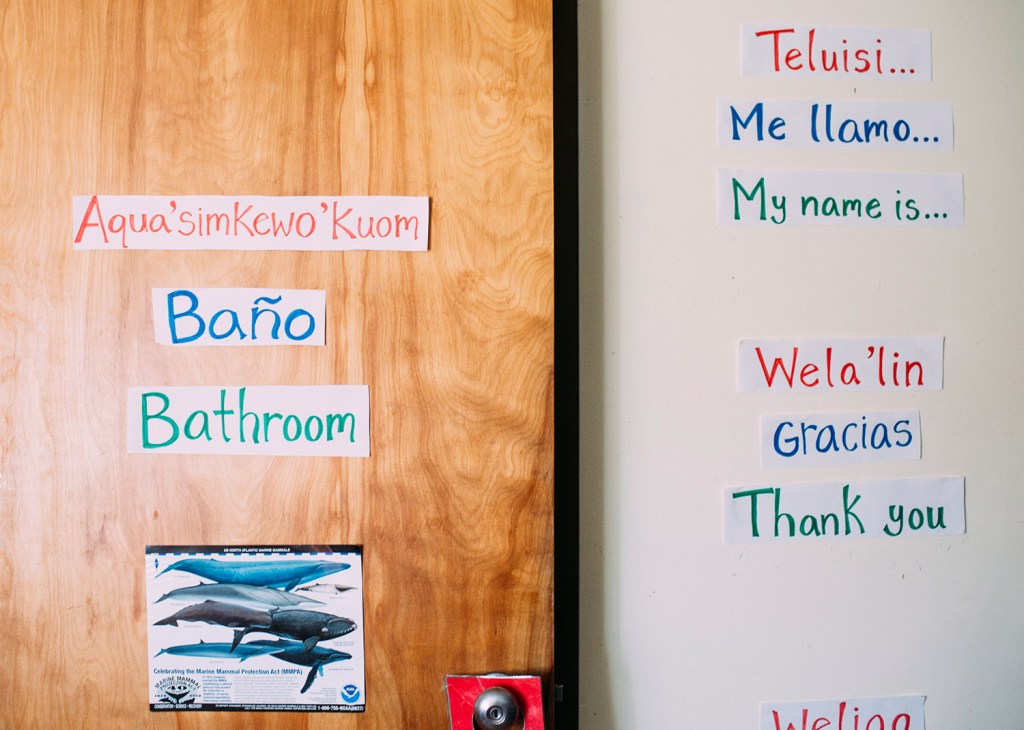

In the classrooms, signs hang with words and phrases in English, Spanish and Micmac, along with brightly colored drawings and self-portraits. On one wall is a map where students have drawn lines from their hometowns to other stops during their migration before coming to Maine.

Older students, who start raking at 14, are offered tutoring services at their camps after they come in from the fields, and on weekends are invited to tour the University of Maine in Orono and given tips on finding a job or writing a resume.

“They are in a school where they are the number one priority,” Yaffe said. “We exist for them. It’s their school and their parents’ school – not the other way around.”

The school is constantly in flux, with a mix of new and familiar students. Many are returning in the annual migration from their home, while others are arriving for the first time. Last year, the average number of days attended by each student was eight – students come and go depending on their parents’ situation, and some older students work some days and come to school on others. Some students are Passamaquoddy from Maine, but qualify for migrant education services because their families crossed a school district boundary to work. Other students come from away but have settled in the area and qualify for migrant education for three years.

The federal Migrant Education Program, created in 1966, provides funds nationwide so students can continue their education, including testing and grade-specific programming, even as they move around the country. A centralized reporting system allows the states to record how many days students attended school and share educational and health information as students move from state to state. The program had nationwide funding of $374.7 million in fiscal year 2014.

Yaffe said Blueberry Harvest School staff members work to establish strong ties to the students and their native cultures.

“It’s really about celebrating their identity,” Yaffe said.

Teachers use books in the students’ native languages, and 70 percent of the school staff is bilingual, he said.

‘A PASSION FOR LEARNING’

In past years, the school has operated out of various locations, including space at University of Maine at Machias. Being able to use Harrington Elementary School – with its cafeteria, small scale furniture, playground, age-appropriate books and traditional setting – makes it easier to run the program, Yaffe said.

Five-year-old Ryleigh Googoo is a third-generation Micmac at the school. Her mother, Alexsanderine Stevens, is raking this season, but in the past she attended the school and worked as a teacher’s aide. Her mother, Mary Marshall, has been working with the school for over 20 years as a community liaison. They have more than 20 people in their extended family here for the season, Stevens said.

“It was fun,” Stevens said of her time at the school. “(Ryleigh) talks about it. She didn’t need any convincing to go. She loves it.”

At a parents’ night, the staff served dinner and showed parents a video of their children playing at the school and out at a weekly swimming session in Machias. Augustine led the room in a call-and-response drum song, then an alligator dance borrowed from the Seminole tribe in Florida.

“Aqui! Aqui!” 6-year-old Selena Ramirez called to her parents, leading them to her classroom after the dance. She proudly showed them her artwork on the walls, including a paper cutout of a blueberry and a house with bits of her family’s story: “We moved then we moved again. We stay there until we go back to Florida and then I was happy because I miss my brother.”

Yaffe said the school fills an important education gap for some students, particularly those who are based in states where the school year starts in August and they are considered absent. School days attended in Maine will count toward their overall attendance.

“It’s really rewarding to be able to see the look on kids’ faces as they discover things in the classroom and they develop a passion for learning,” Yaffe said.

“Whether a student is here for only one week or they come every summer, we can help them be prepared to succeed in school this fall.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.