FRENCHBORO — The promise the day before seemed bold and improbable.

“Tomorrow you will see the most beautiful place in Maine,” said Terry Towne, a Maine Coast Heritage Trust land steward, when speaking of the Frenchboro Preserve on Long Island.

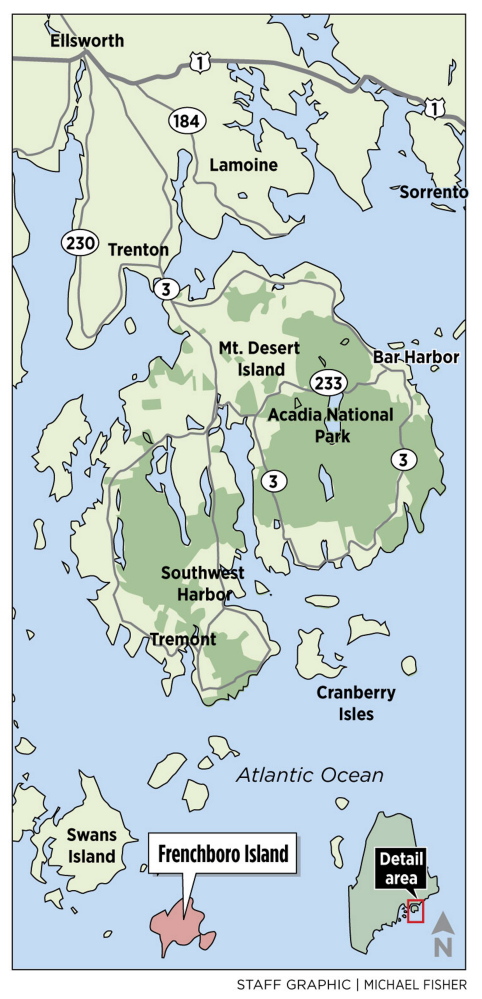

To be sure, Towne, a resident of Mount Desert Island since 1974, is biased. But he’s got a pretty good case. Located eight miles off the coast of Acadia National Park, the island features unusual rock formations and an intimate, often solitary experience with wildlife.

Starting next summer, Frenchboro Preserve will be open to camping for the first time, with two wilderness sites available at opposite ends of the preserve that makes up 80 percent of the island.

Of the 24 island preserves Towne manages for the trust, 14 offer camping. But Frenchboro is the only one with public transportation through the ferry service out of Bass Harbor, making it the most accessible, even if it is the most wild.

Frenchboro has a small, year-round population that relies on the ferry service. But the village in Lunt Harbor makes up a tiny part of the island, of which the trust owns all but 300 acres.

After years of forbidding camping due to the fragile ecosytem and threat of fires, the trust decided to allow limited camping starting next summer to encourage greater use of the island, Towne said. Fires will be permitted at the two campsites, but only near the ocean and below the high water mark at one.

“To be this close to Acadia National Park and come here and see only three to four people is special,” said Towne, the trust’s regional steward since 2002. “And it belongs to the people of Maine. People should see this.”

The trust has owned Frenchboro since 2000 when it purchased nearly 1,000 acres on Long Island. In 2011 Rich’s Head, the 192-acre peninsula that juts out into the open ocean, was donated, and a few other parcels were acquired to bring the preserve’s total size to 1,170 acres.

Across much of the island, the land is made up of rocks and boulders, very little top soil, and plants and trees rugged enough to endure it all. Dead trees overturned by microbursts reveal roots threaded through boulders.

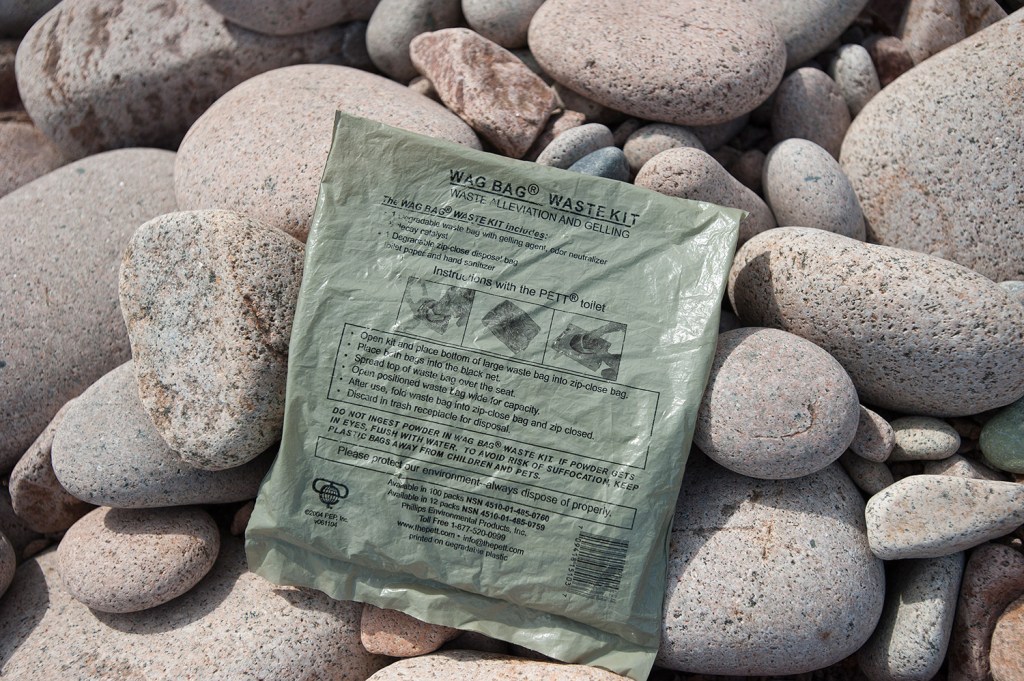

As a result, “leave no trace” camping principals will require packing everything in and out, including human waste, because the soil is too thin to repeatedly dig holes.

It’s a hard way to camp, but the reward is a rare, undisturbed, pristine outer-island experience.

With 10 miles of protected rocky shoreline showcased by a perimeter path, the main trail rivals the coastal path along Acadia National Park, except there are no cars and no crowds.

On Frenchboro you can hike for four hours without seeing another person.

And based on the wilderness camping demand on nearby Isle Au Haut, the one island where Acadia allows camping, Frenchboro’s new camping policy should be a welcome opportunity.

“The absolute peak is July and August. Then all five lean-tos are reserved every night,” said Acadia ranger Kristin Dillon. “The people who come to camp here want to be somewhere more remote. It’s a pretty private experience.”

At its busiest, Dillon said the island can accomodate 30 campers, and they need to reserve sites well in advance.

On Frenchboro, one campsite will be accessed by car on a dirt road that leads to a rocky beach. Here picnic tables offer views of Mount Desert Island’s set of mountains that include Cadillac, Champlain and Sargent. The horizon to the east is made up of other protected islands: Acadia’s Baker Island and Great Duck Island, owned by The Nature Conservancy and College of the Atlantic.

The other campsite, which is more remote, requires a 2-mile hike to Rich’s Head, which looks across open ocean. Campers will have to traverse two natural seawalls built using oval-shaped, backpack-sized boulders.

Most of Frenchboro’s jagged, pink-granite coastline is made up of unique rock formations.

The basalt dikes – well-defined dark sections of rock that indicate where magma moved up through fractured granite – were forged 400 million years ago, said Maine state geologist Bob Marvinney.

“Those dikes extend quite a ways down,” Marvinney said. “And they were perhaps feeders to volcanoes. They could have been flows of lava on the surface, and some of it solidified.”

The conical-shaped rocks on Long Island can be found in other parts of the world, Marvinney said. Still, they represent strange-looking examples of how granite cooled in fantastic shapes million of years ago. It’s not your everyday coastal scene.

“Frenchboro is in our top five,” trust communication director Rich Knox said of its more than 100 coastal preserves.

Frenchboro’s population has declined from 197 at its peak in 1910 to about 65 year-round residents, many who make their living by fishing. Its small village has a museum, church and a store that doubles as a seafood restaurant.

Three simple cemeteries tell a story of islanders who once called this quiet world home. But now mostly terns and gulls dominate the island.

As Towne points out cotton grass, the purple harebell flower typically found in Alpine zones, and the sundew, a carnivorous plant, he repeatedly shakes his head. He looks at ferns and junipers growing off rocks and calls these the “hanging gardens of Frenchboro.”

“You can buy a round-trip ferry ticket to get here for $11.25,” he said. “It’s the best deal in Maine. There is a feeling here that just fills you.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.