ORONO — A socialist candidate (Bernie Sanders) for president? Such would not have been a foreign idea to many Maine workers in the opening years of the 20th century, when the Maine Socialist Party was organized, calling for the public ownership of railways, telegraphs and all other public utilities, and all industries controlled by monopolies, trusts and combines.

Forged on the anvil of discontent over an economic system gone awry, they could be found holding official positions within the established Maine labor movement, marching in Labor Day parades and fending off a litany of negative charges about their nature and purpose.

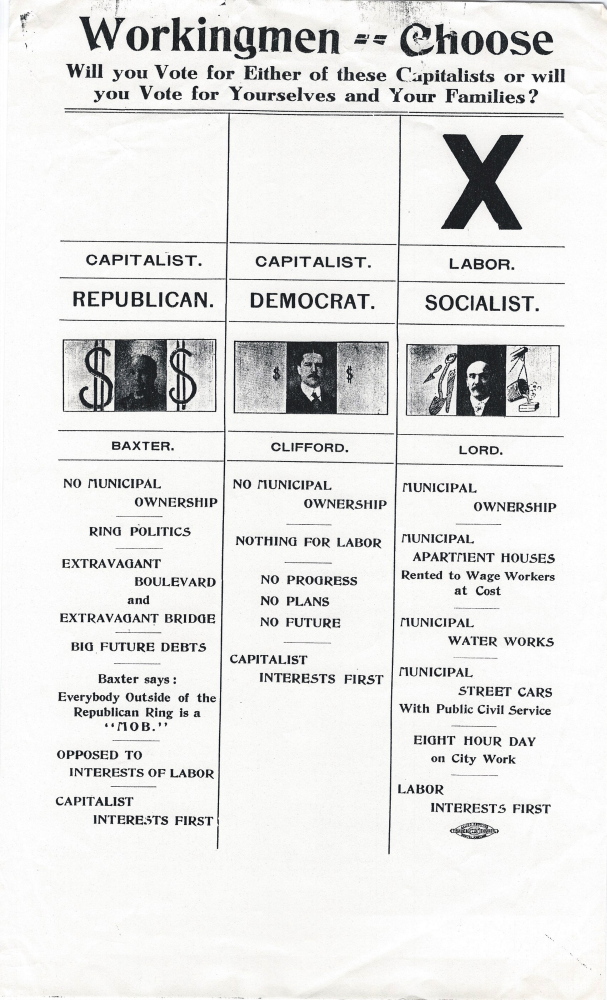

A profile of the Socialist blueprint for escaping “wage slavery” and securing “to the workers the full product of their toil” was evident in the platform of the local iconoclasts in Portland in 1901.

They called for the acquisition, by purchase or through new construction, of utilities such as waterworks, gas and electric light plants and street railways. The profit from operating such public works, they insisted, should be used to raise wages and shorten the length of the working day for workmen, and to improve the service and reduce the cost of such service to the public.

They opposed the sale of public lands and called for the construction of apartment houses with good air and sanitary arrangements, to be rented to workingmen at the cost of maintaining them.

To create jobs for unemployed citizens, the political mavericks demanded that the city create a system of public works and that such work be done by the city and not by contractors. Eight hours was to constitute a day’s work until fewer hours per day were possible. The Portland Socialists also called for a minimum wage of $2 a day, and they insisted that union labor and union wages be paid when unions existed.

The local architects of radical reform further demanded that the city provide “free” employment bureaus (in an age when private employment agencies fleeced workers), and that under the supervision of the Portland Central Labor Union, city work was to be given to those firms that used the union label.

Old-age pensions, the Socialists insisted, were to be paid to city employees who did not have $1,000 worth of property. Their mosaic of demands also called for:

• Disconnecting police and fire protection from politics, since access to public services at that time was linked to the wealth of the neighborhood.

• Employing only the capable and faithful in city positions.

• Not allowing the expression of political opinion to be used as grounds for dismissal from municipal service.

To close the gap in income distribution, the Portland Socialists required that wage increases for teachers and city officials should begin with the smallest salaries, with the tendency toward equalization with the larger salaries. Taking a stand against sexual discrimination and inequality, they insisted that equal wages be paid for equal work, irrespective of sex.

The local disciples of socialism further demanded that the city should establish street sanitary stations and ensure strict supervision of child labor. Schoolchildren whose parents could not support them were to be supplied by the city with food and clothing during their schooling and taken on summer outings – such was considered justice, not charity.

To circumvent the baneful link between wealth and the democratic process and return power to the people, they called for the initiative and referendum. Finally, they called for the establishment of a free public art museum.

The social reconstruction of Portland was to be financed by developing a just taxation system so that the rich and corporations would bear their proper share.

The liquor question – which was inseparable from Maine politics – was viewed as a national question; hence, the Portland Socialists called for the public ownership and control of the manufacture of liquor and the creation of public agencies selling such liquor at cost.

Portland’s leading Socialist was Charles L. Fox, an artist and member and secretary of the Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers of America, Local 237, and several-time Socialist choice for governor of Maine.

He founded an art school that was organized on a cooperative basis, with its students sharing the nominal costs of its operation. The school motto was “to work and to paint for the brotherhood of mankind,” which thematically expressed the socialist vision and quest for the “Cooperative Commonwealth.”

Bernie Sanders appeals to those who still harbor that vision and quest and who hope the socialist ember is about to billow once again.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.