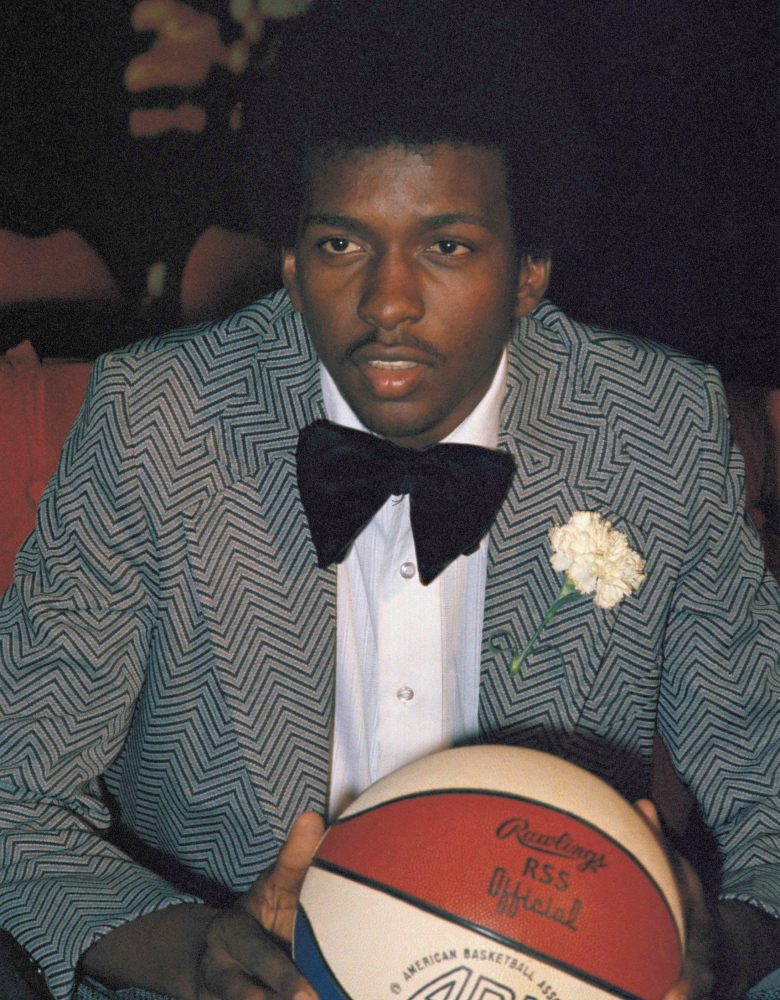

It was the dog days of summer 1974, and University of Maryland Coach Lefty Driesell was very, very angry. He had spent the better part of a year scouting a star high-school basketball player from Petersburg, Virginia, named Moses Malone – 6 feet 10 inches, 220 pounds, 19 years old and, according to one scout, a “pro talent – now.” After a heated recruiting battle, Malone signed a letter of intent with the Terrapins.

But, before his first game, the huge center defected to the Utah Stars, dealing the Maryland basketball program a huge blow. But this wasn’t just about the Terps, Driesell said. This was about a young man – the first young man in history – to forego college and jump from high school onto a pro court. It just wasn’t appropriate.

“I think they’re taking advantage of Moses,” Driesell said.

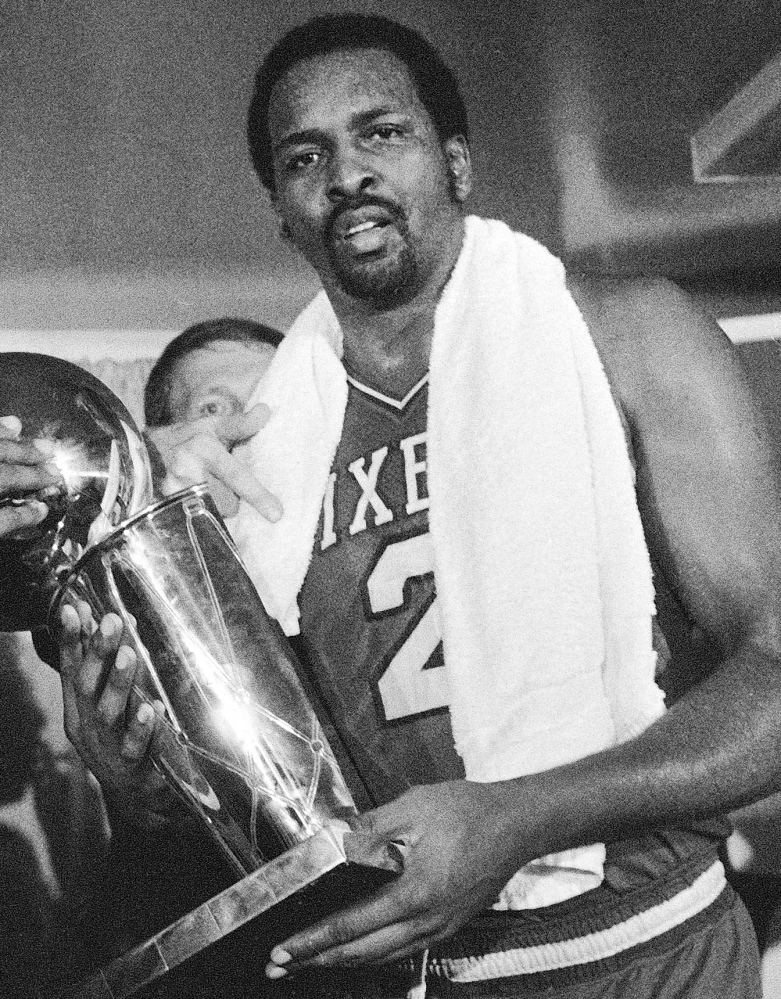

Forty years later, Malone – who died of an apparent heart attack over the weekend at 60 – has left a legacy many an NBA pro would kill for. With 7,382 offensive rebounds, the man who helped take the Philadelphia 76ers to an NBA title was inducted to the Hall of Fame in 2001, the first year he was eligible. But a generation ago, this silent and, some said, not very smart giant was at the center of a controversy about sports and education – and race – that rages to this day.

If the American Basketball Association – which merged with the NBA two years after Malone was recruited – needed the perfect player to justify scooping right out of high school, Malone certainly fit the bill. First of all, he was incredibly poor.

“It was obvious that they were broke,” Larry Creger, who scouted Malone for Utah, told Terry Pluto for the 2007 book “Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association.”

“The house had no paint. There wasn’t any grass where the lawn was supposed to be. The whole neighborhood was like that, extremely poor.”

Malone was an only child of a woman who worked as a Safeway checker for $100 per week. Mary Malone had left school after the fifth grade to keep her family afloat, and kicked Malone’s father out of the house for drinking.

“I didn’t like him to do no work at all,” she told sportswriter Frank Deford of her son in 1979. “I know how hard I come up, so I didn’t want him to.”

The Malone homestead Deford described was little more than a shack – one that was condemned after Malone’s mother moved out once her son got his payday.

“The plumbing often didn’t work, and for a long time there was a big hole in a wall where a window was supposed to be,” Deford wrote. “When the house would become overrun with recruiters, Moses would climb out a window, get onto the roof and take off.”

The recruiters weren’t just supposed to be selling Malone on their college teams. They were supposed to be selling him on college. Malone’s family, however, wasn’t just in dire circumstances. He was also a middling student – at best.

Of the “C” average Malone would need to get into a worthy school: “He doesn’t quite have it now,” Bob Kilbourne, athletic director at Malone’s high school, told The Washington Post in 1974, “but we’re pretty sure he’s going to get it.”

Kilbourne, however, had been working with his star player.

“We’ve had Moses in public speaking class to get him over his shyness,” Kilbourne said. “Before he came to high school, I don’t think he’d ever talked to a white person.”

For Stars scout Creger, Malone’s poverty and lack of academic prospects made the case: He should play pro ball immediately.

“What a joke it was for some of these coaches to be talking to Moses about the value and sanctity of a college degree,” Creger said. “At that stage of his life, Moses couldn’t even put a sentence together. … It was ludicrous for Lefty Driesell and all these guys to talk to Moses about how a college education was what he needed.”

After Malone signed with the Stars, the center’s silence, which some writers linked to his alleged lack of intelligence, became legend. The New York Times referred to him as a “manchild.” Before he was “Chairman of the Boards,” a Utah DJ deemed him “Mumbles” Malone.

Whenever reporters did score what passed for a Malone quote, they often rendered it in dialect accompanied by unflattering descriptions. Even his famous line about the outcome of the 1983 postseason – “Fo’, Fo’, Fo,'” a prediction of three series sweeps in four games could be read as mocking.

“Malone is not particularly articulate,” Deford wrote. “… Indeed, in his heavy bass voice, speaking in the argot of his impoverished Southern subculture, he sometimes seems obtuse.”

Even Malone’s teammates could offer backhanded advice.

“Sometimes the guys’ll get on him about his speech problems; that’s one reason he’s so shy,” Gerald Goven of the Stars told The Post in 1974. “College would have been good for him only if he’d have gone to class. I’ve told him he should go back to school, though, because he’s going to have to speak in public now and then.”

After Malone left the NBA behind, the “Mumbles” reputation stuck. Apropos of nothing, a political reporter ribbed Malone in 1999 in a column about a Bill Bradley campaign event the former player attended.

“If the unintelligible Moses Malone speaks, will there be a translator?” the Weekly Standard wrote.

Even Julius Erving – arguably the greatest 76er ever – got in on the act.

“He’s not a man of a lot of words,” Erving said, inducting Malone into the Hall of Fame in 2001. “But behind those eyes you know there’s a brilliant mind. And it stays ahead of most people most of the time.”

In 2005, the NBA decreed that players must be 19 to enter the draft. A decade later, there are “one-and-done” players who do a year at a college before turning pro. This outcome doesn’t seem to serve anyone.

“College is not for everybody,” Louisville Coach Rick Pitino said earlier this year. “So if a kid doesn’t want to go to college, let him go to the pros.”

Decades ago, another player who skipped out on a degree said Malone – inarticulate or not, uneducated or not – had a similar argument.

“The colleges are just there to use you,” Spencer Haywood of the Jazz, Malone’s teenage idol and the first basketball player ever to leave college for the pros, told Deford in 1979. “If you’re black and haven’t a nice, rich mommy and daddy … then you have no choice. You take advantage of what you have as soon as you can.”

Utah Stars scout Creger put it even more starkly.

“When we drafted Moses, all of these people were trying to lay a guilt trip on us, as if we were robbing the cradle,” he said. “I said that I believed in college for 99 percent of the players in the country, but not for Moses.”

He added: “Think about it. What was Moses Malone better prepared to do, sit in a classroom or play basketball? Also, what did his family need more, Moses at school or some immediate financial help?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.