Another winter’s coming. Another season of tight natural gas supplies in New England, of above-average electricity and gas rates that cost residents and businesses billions of extra dollars every year.

Also coming: Continued debate among politicians and interest groups over the need for and cost of increasing the flow of gas from plentiful new supplies on the region’s doorstep, and who should pay for it.

But with little public awareness, something besides talk and study is actually happening.

Construction started this summer on the first major natural gas pipeline expansion designed to ease a bottleneck that’s keeping more gas from the Marcellus Shale deposits in Pennsylvania and New York from coming into New England. When it goes into service in November 2016, the $1 billion Algonquin Incremental Market project, or AIM, will pump enough extra gas to heat 350,000 homes a day in southern New England.

Wholesale energy markets are starting to reflect this reality. Commodity prices for wholesale gas delivery late in 2016 indicate that the premium New Englanders pay, compared to customers in the New York City area, will begin shrinking. That would be a big deal. New England has been burdened for years with much higher winter gas rates than our next-door neighbors, who have better connections to gas supplies.

Beyond AIM, a $500 million project called Atlantic Bridge is on track to break ground in the spring of 2017. Atlantic Bridge would bring gas from the south into Maine for customers of Summit Natural Gas and Maine Natural Gas. It also has contracts with manufacturers including Woodland Pulp in Baileyville, on the New Brunswick border.

These developments are early signs that the private sector is stepping up to ease the costly natural gas-supply crunch in Maine and New England.

“I don’t want to give the impression that things have been solved, but it is a dramatically different energy situation than the summer of 2014,” said Patrick Woodcock, director of Gov. Paul LePage’s energy office.

For this winter, Woodcock is encouraged by the falling price of oil, which is used by back-up power plants if natural gas is expensive or scarce on the coldest days. It will give Maine some breathing room while new pipelines are being built.

These factors also offer hope that homes and small businesses in Maine will see another year of stable or falling electricity rates. The global collapse of oil prices last fall led to a 13 percent rate drop for Central Maine Power customers who buy their power through the state’s default service, called the standard offer. The Maine Public Utilities Commission sent out bid requests this month for one-year service beginning in January for customers served by CMP and Emera-Maine.

But Woodcock and others warn that relief may be short-lived.

Neither of these pipelines has firm contracts with power plants, which generate more than half the electricity in New England. Those projects would depend in part on state regulators approving agreements in which electricity customers would help pay for pipeline capacity. A regional attempt to orchestrate that failed last year.

In Maine, the PUC is investigating whether added capacity could lower costs for consumers. After 19 months of complex legal proceedings, the case shows no signs of concluding.

There’s so much focus now on natural gas in New England because it has become the default fuel for much of the new power generation, as pollution-prone plants that burn coal and oil are retired. Renewable energy advocates are unhappy about this emphasis. They say the push for gas crowds out cleaner alternatives, namely wind and solar.

At the same time, some residents worry about the safety of gas lines buried near their homes. Others oppose the way natural gas is gathered by injecting chemicals into underground rock deposits, a process called hydraulic fracturing. Still others are against fossil fuel development because it contributes to climate change.

Against this backdrop, energy companies are jockeying to overcome resistance and get strategic projects built.

AIM had plenty of local opposition from residents in southern New England. But it easily won regulatory approvals in part because 93 percent of the project is within the existing right of way of the Algonquin Gas Transmission line, one of two major pipelines already running under southern New England.

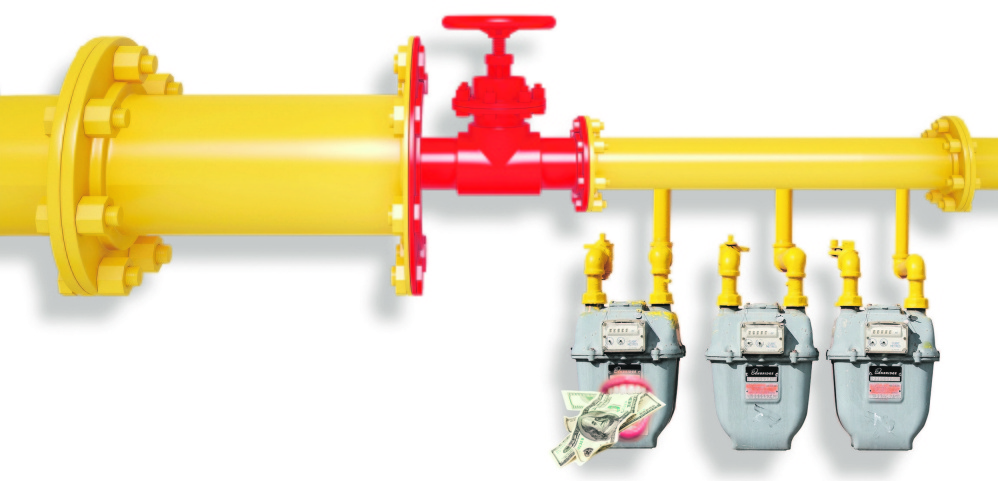

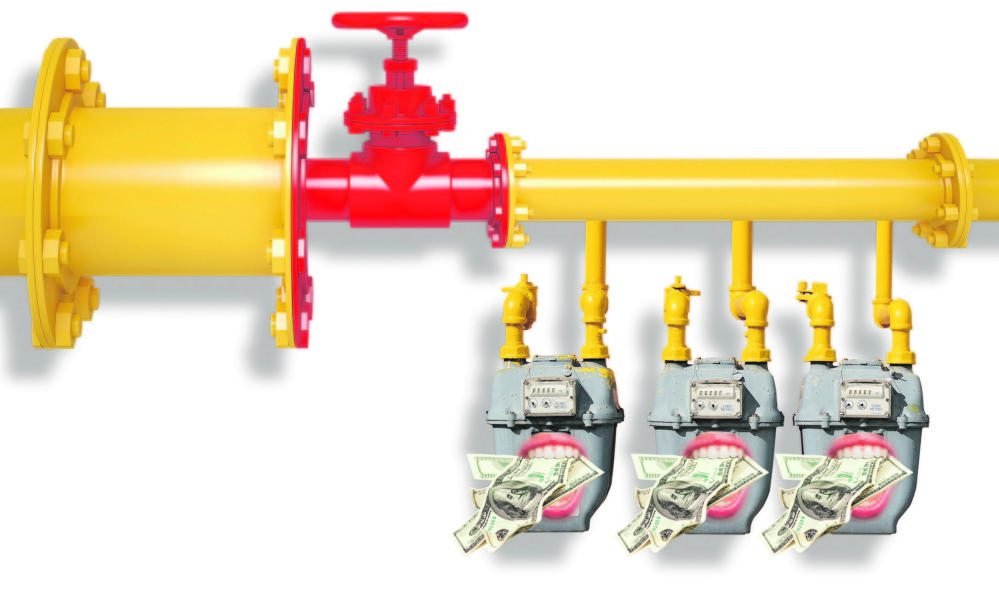

A key part of the work is around a compressor station in Cromwell, Connecticut, south of Hartford. Cromwell is a choke point in the winter. There’s not enough capacity there to handle additional volumes of gas into New England. This summer, crews are building a two-mile loop with 36-inch diameter steel pipe to open that bottleneck. They also will add roughly 35 miles of new pipe between New York and Massachusetts and add six new compressor units at existing stations.

AIM and Atlantic Bridge are being developed by Houston-based Spectra Energy.

“There’s definitely going to be some impact on the price of gas in New England versus New York,” said Greg Crisp, general manager for business development at Spectra. “The (price difference) is going to go down because of those two projects. That will translate into energy cost savings for all users in New England.”

But the extra gas will be largely used by local distribution companies, not power plants. Spectra has proposed an additional project called Access Northeast. It could connect 70 percent of the region’s power plants, including the Westbrook Energy Center in Maine. But that pipeline would require electric utilities to contract for gas capacity and charge ratepayers.

Beyond that, power plants aren’t anxious to sign firm contracts for gas supply.

Dan Dolan, president of the New England Power Generators Association, said his members favor a competitive, open-market approach over regulation. He noted several major power plants being developed or proposed in southern New England this year as evidence that the industry is responding to market conditions. Most will run on natural gas.

“What all these projects have in common is a reliance on market fundamentals and putting their own capital at risk,” Dolan said, “without the promise of a long-term contract or ratepayer guarantees.”

But Tony Buxton, a Portland lawyer, said the reason generators don’t want long-term contracts with pipelines is because they earn larger profits when power prices spike.

“The generators don’t want anything built because they are making money hand over fist,” he said.

Buxton is representing North America’s largest energy infrastructure company, Kinder Morgan. The company wants to build a new spur from its Tennessee Gas Pipeline across Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire. Called Northeast Energy Direct, the project would be several times larger than AIM and bring added gas supply to southern New England and Maine late in 2018.

Kinder Morgan cites dozens of studies that show the pipeline would save New England electric customers more than $2 billion a year and avert anticipated gas shortages. But the project faces pushback from residents in western Massachusetts.

For Buxton and large energy users in Maine, new pipeline capacity must temper the steep spikes in wholesale electric prices on the coldest winter days, when natural gas demand is high. On those days, hourly rates in New England can soar many times higher than those in the New York City area.

Futures prices for electricity supply in 2017 and 2018 indicate that the gap between New England New York prices will start shrinking. But John Rosenkranz, a gas-supply consultant in Acton, Massachusetts, said that while the market is responding, it’s not clear how much the spread will narrow.

Rosenkranz, who has advised the Maine Office of Public Advocate, said Maine is at greater risk for price spikes because gas supplies from Atlantic Canada through the Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline are diminishing and being rationed to obtain higher winter rates. Atlantic Bridge and Northeast Energy Direct could help compensate for that, by bringing a new supply from the south.

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Twitter: TuxTurkel

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.