HINCKLEY — The sun wasn’t shining Wednesday afternoon, but the lights were still on at the Maine Academy of Natural Sciences, where the school recently installed more than 200 electricity-generating solar panels.

The panels are part of a $7 million renovation and expansion at the Charles E. Moody School, a former grammar school on the Good Will-Hinckley campus that is now home to the charter high school.

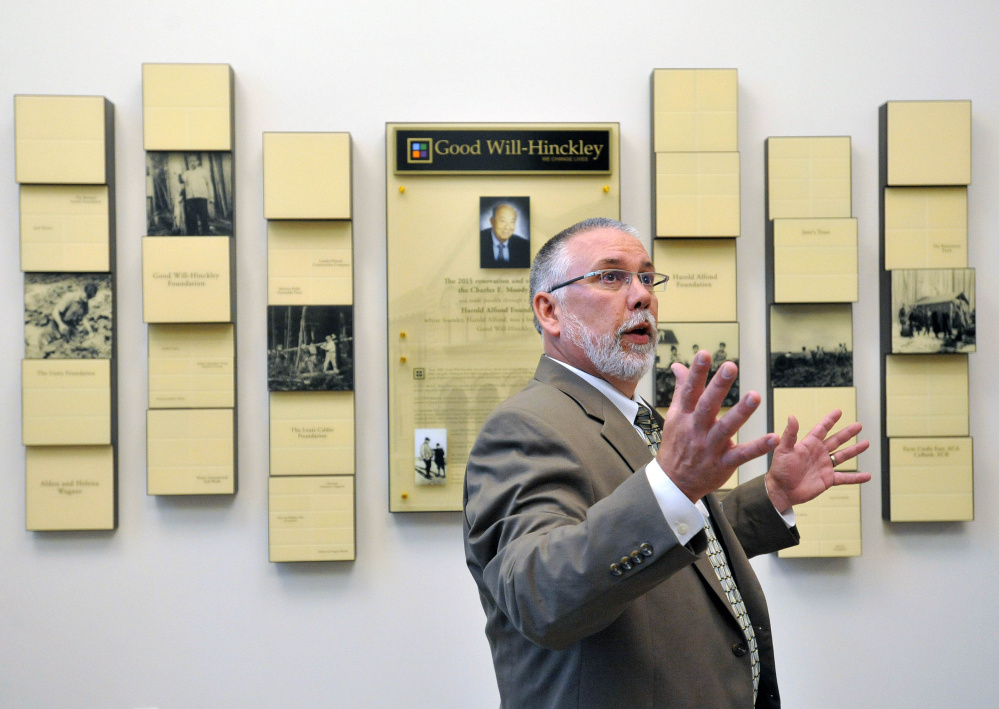

“The reason we had to expand was the demand,” said Rob Moody, interim president of Good Will-Hinckley and the Maine Academy of Natural Sciences, during a tour of the building Wednesday. “There are a lot of kids that want to come here, so we had to find a place to fit 200-plus kids.”

The school’s current enrollment is about 125 students, according to Moody, and the school hopes to expand to a student population of about 200 in the next three years. It is on the Good Will-Hinckley campus, which is also home to the L.C. Bates Museum, the Glenn Stratton Learning Center and the College Step Up Program.

‘A REAL FEELING OF COMMUNITY’

Students and parents at a ribbon-cutting Wednesday said they were pleased with the renovated building, although some had reservations about growing the student population.

“I know it’s good for a school to grow, but right now we have a real feeling of community because we’re small,” said junior Hannes Moll of Windsor. “I feel like that could decline a little with more kids.”

Moll’s mother, Leanne Moll, who was also at the ceremony, said the school has helped her son’s self-confidence and also helped her as a single parent.

“It’s hard as a single mom to raise a son, but the male teachers here are really role models and have really been a good connection,” she said.

“I was like, ‘Wow,’ ” Moll said, describing her reaction when she walked into the updated building for the first time. “Before they had really tiny classrooms, but they made it work. The building is only as good as the people in it, and I think (the staff members here) are already doing a really good job.”

The renovation of the Moody School into a home for the charter school has been in the works since the school opened in 2012 as the state’s first charter high school, Moody said.

‘FOCUS ON SUSTAINABILITY’

The building was built around 1905 as part of the Good Will-Hinckley Home for Boys and Girls, a home and farm where orphaned and needy children could get an education. The residential school closed in 2009, citing financial reasons, and the charter school opened in its place in 2012. The school is open to students from around the state and offers a curriculum based in agriculture, forestry and hands-on learning.

“The focus on sustainability is part of our mission,” Moody said. “We’re teaching that in the classroom, and this is one way of carrying out what we are teaching.”

He said the century-old Moody School, which was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986, was in good condition when renovations began in 2012. The exposed brick of the old building can still be seen within the walls of the new structure, which includes a 7,000-square-foot addition. The building is 23,350 square feet total and includes 17 classrooms and 267 photovoltaic panels – solar panels that use the sun’s energy to generate electricity.

Members of the Good Will-Hinckley board of directors and contributors to a $10 million capital campaign funding the renovation and an endowment said they were excited about the building.

BUILDING IS ‘NET POSITIVE’

The Maine Academy of Natural Sciences “has had to turn students interested in attending the school away each of the past two years,” said Good Will-Hinckley board of directors Chairman Jack Moore. “Today we are on our way to achieving the vision of serving over 200 students from across Maine each year.”

“We are delighted to see Good Will-Hinckley take this exciting next step toward serving more Maine youth at the state’s first charter school,” said Greg Powell, chairman of the Harold Alfond Foundation, a contributor to the capital campaign.

The solar panels are expected to produce 91,000 kilowatt hours of electricity per year. The building is also “net-positive,” which means it generates more electricity than it will use. The remaining electricity can be used to run other buildings on the campus or can be sold back to the electrical grid.

The installation is one of several large solar projects to be built at academic facilities around the state in recent years. In 2012, Thomas College in Waterville erected what was at the time the largest solar panel system in the state with the installation of 700 solar panels on the roof of the Alfond Athletic Center. The panels continue to generate about 11 percent of the school’s electrical needs.

Unity College also has made strides in solar energy on its campus with solar panels on the Unity House, where the school’s president lives, and in residential facilities such as TerraHaus, a dormitory building that covers most of its heating costs with thermal solar panels.

Jennifer deHart, sustainability director at Unity College, said there are significant challenges to generating enough solar electricity to run an entire building.

“To put up enough panels to run a conventional building is way more than most buildings can accommodate,” she said. “So it requires you to first shrink the energy requirements of the building and then your solar array can be sized.”

Rachel Ohm can be contacted at 612-2368, or at:

rohm@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.