“A Tale of Three Cities” at the Portland gallery of the University of New England turns a lens to Portland, New York and Paris. Curated by UNE Professor Emeritus Stephen K. Halpert, it is a large exhibition featuring about 100 photographs by Maine artists both active and late.

If your purpose is to see a great deal of excellent photography, “Three Cities” will not disappoint. Like most viewers, I self-select when I go through shows: I linger on the works that hold my interest and I pass by the ones that don’t. In that mode, “Three Cities” was rich and deep.

As an organized exhibition, “Three Cities” is less coherent. How the three cities relate to the included photographers is not particularly clear. Is Portland being proffered as a colleague to the two art centers that have led the art world since photography was invented? Is Portland being placed in their shadows? Or, more likely, is “Three Cities” a show that looks to the connections between Maine photographers and these leading centers for photography? In fairness, Halpert’s exhibition comfortably lets viewers draw their own conclusions from their own associations. But the more I thought about the subject, the less it made sense to me.

My guess is that Berenice Abbott is the subconscious cornerstone to “Three Cities.” She famously worked in Paris with Man Ray and – more quietly – ultimately settled in Maine. One of Abbott’s images of New York was the first work acquired via purchase for the UNE collection: an architecturally sober photograph of a block of row houses on Manhattan’s lower Fifth Avenue.

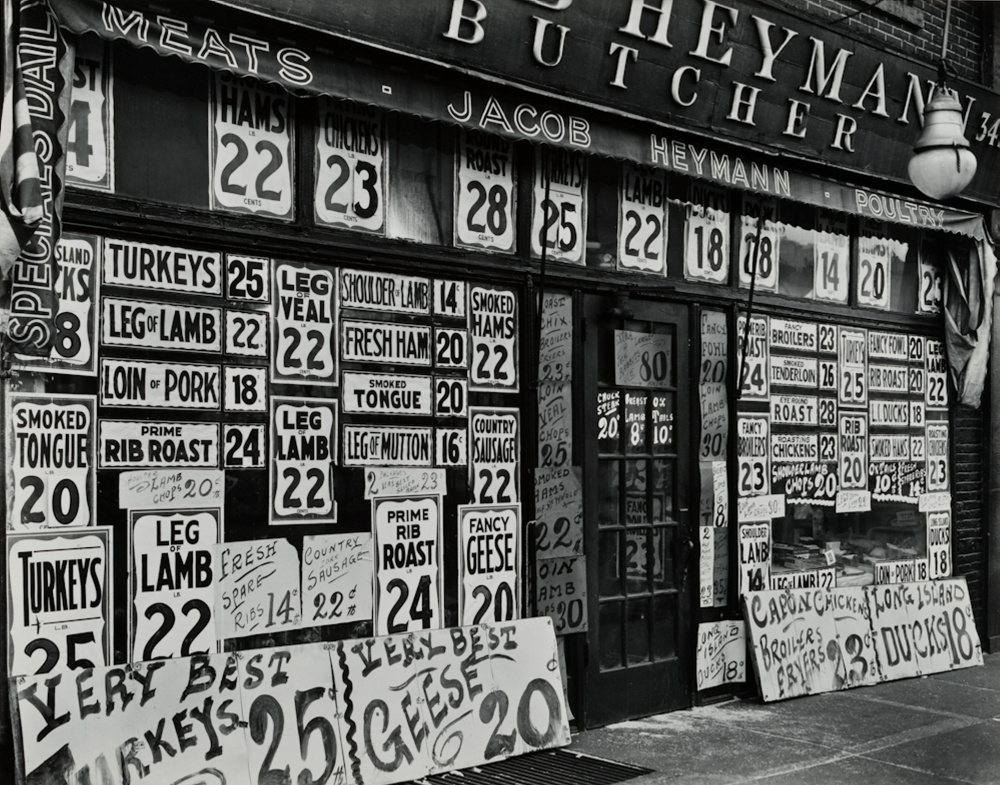

A more exciting image by Abbott features the front of a New York butcher shop plastered with signs advertising that geese ($.20), duck ($.18), leg of lamb ($.22) and rib roast ($.24) were all less expensive than turkey ($.25). (Even if you do get caught up in the content, it’s still a great photograph.)

In fact, all five of Abbott’s works in the show are images of New York, begging the question: “What about Paris and Maine?”

One image that seems to answer the connection question rather directly is the first work viewers will pass: Heath Paley’s “Afternoon Break” features a leather-jacketed young woman taking a smoke break in front of Portland’s “Joe’s NYC” pizza joint. As a color photograph, it’s impressive and exciting. The bright red storefront pops from the brick building, underscored by primary companions of a yellow poster and blue lettering in the window. As a document of Portland, it’s even more fascinating: Two red hearts left by the anonymous Portland “Valentine’s Day Bandit” let us know the time of year and thereby explain the melting ice and the plight of the cold weather smoker in an urban setting.

Paley is typical insofar as his best works soar but he would have been better served by having a couple of his works edited out. A view down into a park is rhythmically exciting and wittily pretends to be an architect’s rendering with passersby unselfconsciously photoshopped in. But in the context of this show, an interior shot and a scene of a cruise ship towering over the Portland waterfront feel more technical than artistic, so they don’t add to the conversation.

Dave Wade suffers similarly. His images of the pilings under a Portland wharf and a gorgeously green and pink Old Port night scene are exquisite. But his image of a sailboat, for example, feels like a snapshot in the context of so many excellent images.

Because “Three Cities” has far too many works, there is more urgency to the sense that the lesser images should have been culled. It’s distracting, for example, to see six of Ruth Sylmor’s fine shots of Paris – dissimilarly sized and framed – jammed into a grid of six on a tiny wall, or Diane Hudson’s five large color images hung so close their frames appear to be touching. It’s uncomfortable, and it was avoidable. Hudson would have been better served if her wall featured only her fine image of Zeitman’s Corner with playful tensions between the 3D flow of the streets and the 2D structure of the image.

In fairness, some visitors may rather see 100 photographs jammed together than 50 hung with space. If that’s you, there is little to disappoint. Even a work I didn’t particularly care for, Darrell Taylor’s “Metropolis Redux,” a cartoonish digital collage caricature of the Big Apple, offers a chuckle by putting Donald Trump out front and center of the city.

I have primarily spent my visits to “Three Cities” lingering on my favorites. Ernst Haas’s Times Square, dizzying with nighttime reflections on a rainy night, calls out 1957 with “West Side Story” on a Broadway marquis. Todd Webb’s “St. Luke’s Place” is a deliriously beautiful snow scene in a residential neighborhood in New York that lilts down from an upper window of what we expect to be a cozy apartment. Melonie Bennett’s Portland “Bartender Trick” looks fun at first and then rewards a longer look with unexpected forensic depth about when and where. Jan Pieter van Voorst van Beest’s covert subway shot of an absorbed tough guy in a white shirt is simply gorgeous, but with an odd punctuation about questionable permission: The subject is unaware of the camera and he doesn’t necessarily look like the sort who would brook such a secret snapshot. Judy Glickman Lauder’s Paris is a place of people and fleeting scenes of things we want to see, but for the moment, can’t reach; her “On the Seine II” passes by a hampered glimpse of the Eiffel Tower. It’s an insightful image of place, but place as the product of individual perception, psychology and cultural priorities.

In terms of broader themes such as subject, craftsmanship, the breadth of included artists and content, “Three Cities” certainly has some flaws. Nonetheless, it is one of the most enjoyable facets of this year’s largely excellent crop of photography exhibitions associated with the Maine Photo Project.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.