When author and critic Sven Birkerts began teaching at Bennington College in Vermont, the place was a world apart. It was quiet, green, idyllic. That was 20 years ago, before the advent of tablets and smartphones. Today, as director of the Bennington Writing Seminars, Birkerts sees digital distraction everywhere.

“The infiltration has happened,” he says, of technology on campus. “It has changed the feeling of things. I don’t feel like we’re leaving one world and going into another. We’re in the same world; it’s just a prettier background.”

Birkerts, who’s best known for “The Gutenberg Elegies,” his 1994 lament about the future of reading in an electronic age, has spent the last two decades thinking and writing about how technology affects us. Though he’s no Luddite, he worries about what we gain, and lose, as technology increasingly dominates modern life.

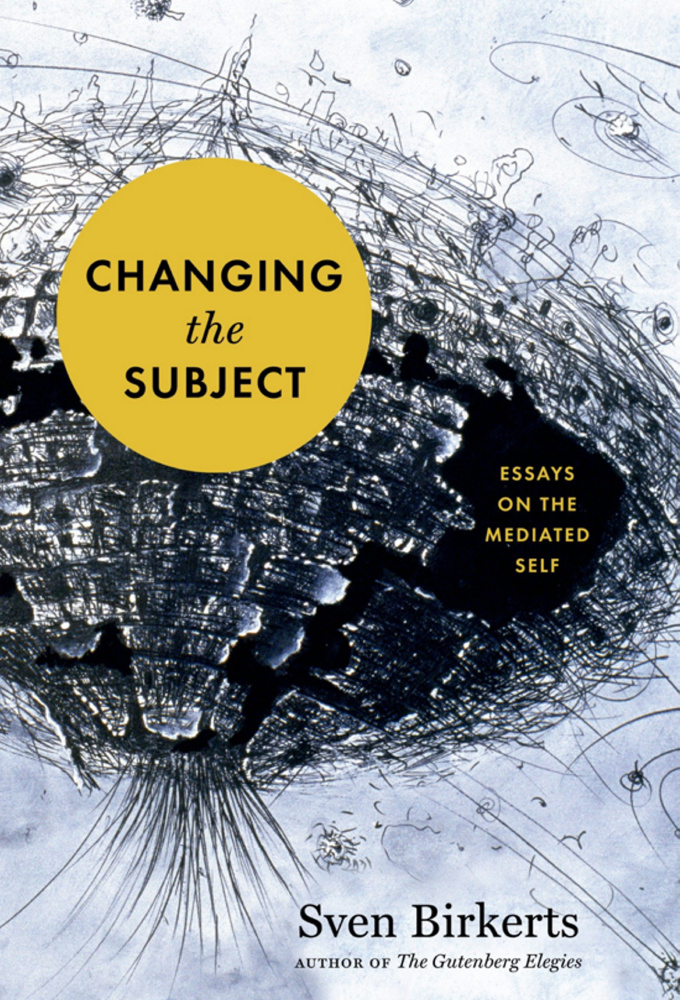

His new book, “Changing The Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age” is a collection of essays continuing his exploration of these themes. We spoke recently about addiction, Harry Potter, the Kindle and clickbait. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do you regulate your online life?

A: Well, I have to be online in my various work capacities. I don’t do Facebook or Spotify, but I have succumbed to Twitter. I see it as a kind of billboard for stray observations. It almost doesn’t count as reading.

Q: You say that “modern living finds us enmeshed in systems that we think we require.” How did we go from developing these new tools to suddenly they’ve become requirements?

A: That’s such a complicated question. I think two things have combined. One is the extraordinary level of engineering sophistication that we’ve arrived at. Also, there’s the insidious and relentless logic of capitalism, which will look to find a way to monetize anything and everything. You know, you step in an elevator, there’s a television. You get in a cab, there’s a television. All of it’s there to try to sell you something; it’s not a public service.

A: We get habituated to it, and once that happens, the sensation meters have to be turned up for anything to reach us. It’s exhausting because we use such a large part of our available awareness just processing the environment. It creates this spiraling escalation that things at every moment have to be a little more vivid, more interesting, more catchy.

Q: It sounds like you’re describing cocaine! Even the language of habituating and increasing the stimulus – that’s a drug, an addiction.

A: The interesting question is what we’re addicted to. It’s not to the information itself. I think it’s an addiction to that feeling of “if something happens, we’ll be there.”

There were so many extraordinary impacts of the World Trade Center collapse. One that doesn’t get talked about much is the idea that the most extraordinary thing could happen at any second. We’re talking about a psychological process that pulls us all into the same amniotic bag, which is an information culture. We’re linked by the simultaneousness.

Q: You talk about “our persistent sense of deferred expectancy” – some unnamed thing being just a click away.

A: There’s such an interesting term that they have now – clickbait. I remember that sensation even as a kid when I went fishing. You stood there, the lake was completely calm and uninteresting, but you were riveted by the sense that, at any moment, something’s going to take the bait. And sometimes it did. I suppose that’s true when we poke around online: Nothing, nothing, and then “Oh my God, look at this!”

Q: Is there a way to have an online life that isn’t addictive?

A: No, I actually don’t think so. You know, I quit smoking, but it took forever and there was a huge amount of delusion. Part of it was “if I just smoked two cigarettes a day, that wouldn’t be a problem.” I guess everyone would have to have an ideal notion of what Internet health is. It is so woven into almost everyone’s work life in a thousand ways. And once you’re online, the real trick is how disciplined you’re going to be. You’d have to be a saint just to use the Internet for business, and not be drifting off into idle whatever.

Q: You talk about works of art being feats of concentration, and feeling envious watching someone reading a book, being absorbed in that world. Are there other ways to find refuge from so much information?

A: Art is a specific example that allows us to have the experience of complete immersed duration. We can get that when we’re having a great conversation that’s not being interrupted at every second. We can get that on a really good walk, where finally we get into the rhythm of it and all the peripherals fall away. Or you can be gardening, or cooking, when you’re fully engaged, and not doing other things. What distinguishes these situations is that they’re uncontaminated by electricity.

Q: You’ve referred to reading as a form of communion when it’s not just a path to information.

A: When Harry Potter swept the world, all these kids had the experience of spending time with a book and being completely absorbed. The implication was that they’d want that experience over and over, and it would open wide the field of literature once again. But I don’t know that that necessarily happened. For many people, it was a kind of one-off. They had their Harry Potter, and now they’re back to watching “Game of Thrones.” It didn’t create a sort of lifetime quest for the reading experience.

Q: Do you believe there’s a fundamental difference between reading hard copy versus reading the identical material on a Kindle?

A: I do. We know when we’re reading the actual physical book that we’re in a different environment. We know that the words stop at the end of the page – they dead-end there. It’s us and the book, two physical entities. When we’re looking at anything that’s powered by a screen, there is an implicit sense that we are in the world of screen mentality. It’s almost like a reflex. One big thing that’s already happened is how rarely the Kindle is just a different reading surface. More and more, it’s becoming so many other things. It’s inevitable that once the isolated, confined thing that is the book is mainly a screen activity, it’s going to be completely open to music, sidebars, videos, voiceovers, whatever. If you want to see what Madame Bovary’s clothing looked like, you’ll hit the button and find out.

Q: Except that there will always be readers who will want the option of the plain book, text on a page, no bells and whistles.

Exactly. I even resented having little line drawings in my Hardy Boys books!

Q: In the book, you describe a pervasive sense of people finding their attention wandering while they read. Is that a result of fractured attention online?

A: That’s part of it. I think we’re getting to the point that there’s little distinction between off-line and online. Rather it is this environmental thing that we’ve been talking about. It’s a new set of reflexes that we’re gradually incorporating. It’s not just multitasking, but a peripheral scanning and screening as we’re doing the thing that we set out to do. One of the fallouts is that it’s much harder to get and hold people’s attention on any one thing.

B: Are you working on any new projects?

A: I’m working on various essays. As we speak, I’m trying to write about why, at this stage in my life, I should have become so addicted to taking pictures with my cellphone. I’ve just totally succumbed to the little camera. I’ll be going along and, all of a sudden, I’ll say, “That’s a fantastic tree, cloud, whatever,” and I’ll stop and take a picture. Then I’ll study the picture, edit a little bit. This is giving me a great new pleasure. I’ve also been writing about my devotion to the novel “To the Lighthouse” by Virginia Woolf. I’ve been writing these meditations – just taking a particular scene, or even a sentence, and looking at it.

Q: Which is exactly what you describe in the book about reading as a conduit to oneself and one’s thoughts.

A: I may not have seen that connection. But, yes, I’m probably doing it for those reasons: to locate something that you really think is good and then just try to figure out all the layers, how it relates to your own memories, your own life.

Q: Isn’t that a big part of why we read in general?

A: I think so. It’s a big part of why I read. There’s so much to think about, isn’t there?

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.