GORHAM — Jim Hughes, 87, sits at the table in his sunny kitchen, a cup of coffee in one hand and a scrapbook in the other. He’s wearing an olive green sweatshirt with the U.S. Marine Corps insignia on front.

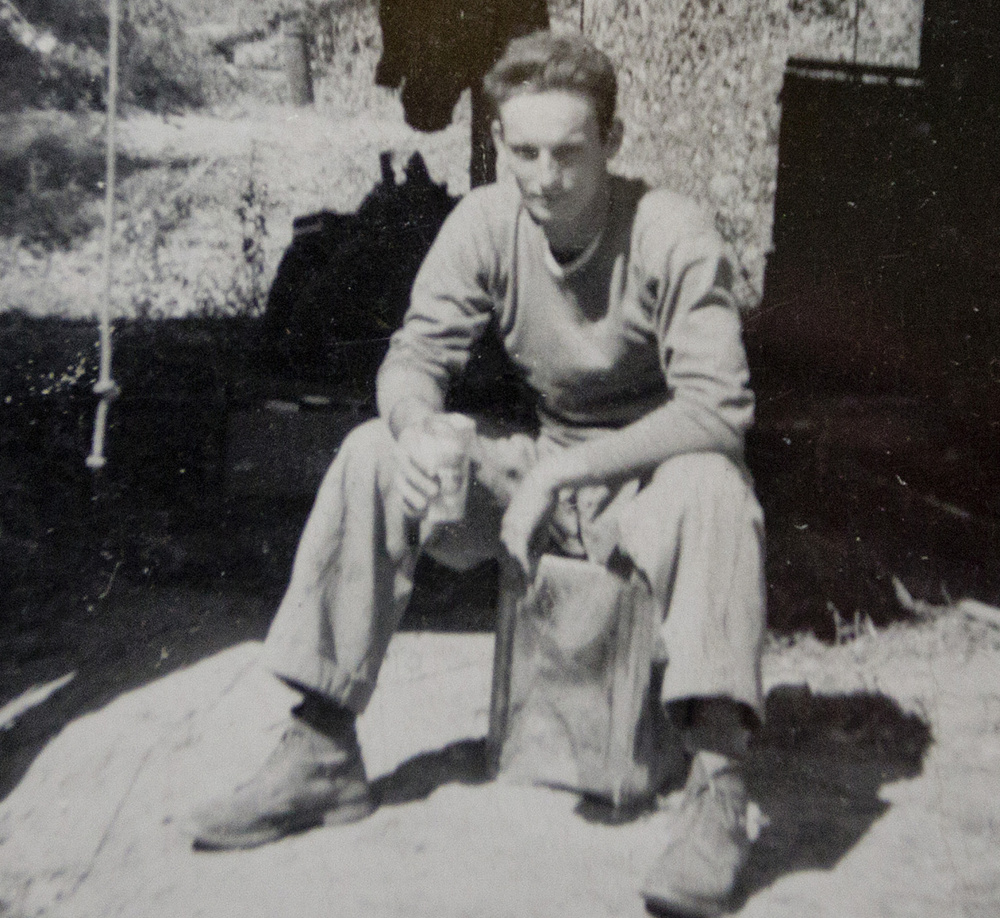

“Right there, that’s me,” he says, pointing to the face of a handsome 22-year-old in an old black and white photo of his Marine platoon. “I was one of the lucky ones.”

“Lucky” is not a word most people would use to describe what Hughes experienced 65 years ago this month.

In November 1950, Hughes, a private first class with Weapons Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment, found himself smack in the middle of one of the most brutal – and pivotal – battles of the Korean War.

In a surprise attack by Chinese forces, 15,000 U.S. troops were surrounded and vastly outnumbered at Chosin Reservoir, a man-made lake in the mountains of northeastern Korea. For 17 days they fought off the relentless strikes that came in the dead of night.

“(The Chinese troops) would blow bugles and beat drums, and they’d come up the mountain right at you by the thousands,” Hughes says.

U.S. troops were fighting more than one enemy at Chosin Reservoir: A frigid air mass had swept in from Siberia, settling over them like a blanket of ice. The battle was quickly dubbed “Frozen Chosin.”

“Not only did they have the bitter cold,” says Beth Crumley, unit historian with the U.S. Marine Corps, “but it was snowing and it was windy.”

Temperatures plummeted to 30 below zero. Food froze. Weapons froze.

“There were almost 9,000 nonbattle casualties, most of them from frostbite and pneumonia,” Crumley says, referring to both deaths and injuries.

Many of the troops didn’t have proper winter gear. Hughes was outfitted with rubber boots that made his feet sweat. When he stopped walking the sweat would freeze.

“I took off my boots and my socks, and (my feet were) kind of red, yellow, black. You could wipe the slime right off of ’em.”

He saw horror everywhere he looked.

“You’d see hundreds of Chinese and North Koreans – they looked like statues. Frozen. Just frozen. Because the Chinese, all they had was their quilted uniforms on. And sneakers.”

He was cold, scared, lonely and hungry.

“It was hell,” he says. “That’s what it was.”

With air support from the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps, the Marines on the ground began to fight their way out of the reservoir and back down the only viable escape route: the treacherously steep Toktong Pass.

“It was an old, rough trail,” Hughes says. “There weren’t any roads up there. Sometimes we only went a hundred yards in a day because of the fighting. The Chinese were on either side of us.”

Fox Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, held the high ground over the Toktong Pass and, despite being outnumbered themselves and suffering immense casualties, managed to keep it open. The company’s commanding officer, Capt. William Barber, was later awarded a Medal of Honor for his courage and leadership.

It took 15 days for the troops – and the 91,000 Korean refugees they brought with them – to reach the safety of the coast.

Hughes, who had been promoted to the rank of sergeant by the time he left active duty, arrived home in Maine in 1952. He went to work as a dispatcher for the Portland Fire Department. He and his wife, Glenyce, raised four children.

He spent the next six decades fighting demons in his sleep.

“He had such horrible nightmares,” says Glenyce, “but I guess you do when you go through (what he did).”

Some people might choose to close the door on those memories and lock it tight. Not Hughes. He made it his life’s work to share the story of Chosin Reservoir.

“I still meet people who don’t know anything about the Korean War,” he says, shaking his head, “never heard of Chosin Reservoir.”

He proudly wears a cap with “Chosin Few” – the nickname given to those who fought there – emblazoned on the front. His pickup truck is a moving billboard, festooned with bumper stickers and decals commemorating the battle. It often prompts people to ask him about his service.

“I still get emotional when I talk about it,” he says.

But talk about it he does. It’s the only way he knows to honor those who didn’t come home.

“The ones that didn’t (make it) are the ones that made it possible for me to get home,” he says. “I’ll remember all my buddies till the day I die.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.