SOUTH PORTLAND — Norma Spurling was only a year-and-a-half old when a plane piloted by her brother, 2nd Lt. George Hout, disappeared during World War II in the eastern Himalayas on a cargo mission between India and China.

Seventy-one years later, Spurling has not given up hope that the remains of the brother she grew up hearing stories about may be recovered. But for now, she said, she clings to the stories and a box full of love letters he wrote to his girlfriend.

“He is right here,” said Spurling, tapping her chest.

Spurling, who still lives in the family home in Bar Harbor, was one of about 230 people from across the Northeast who showed up at a forum Saturday to hear the latest news about the ongoing efforts by the Department of Defense’s POW/MIA Accounting Agency to retrieve their loved ones who disappeared during military conflicts dating back to World War II.

About 83,000 U.S. serice members were missing in action during those conflicts, including 73,000 from World War II. About 6,560 of those have been accounted for. A total of 480 service members from Maine are missing in action from World War II and the Vietnam and Korean wars. Twenty-one have been accounted for and returned to their families.

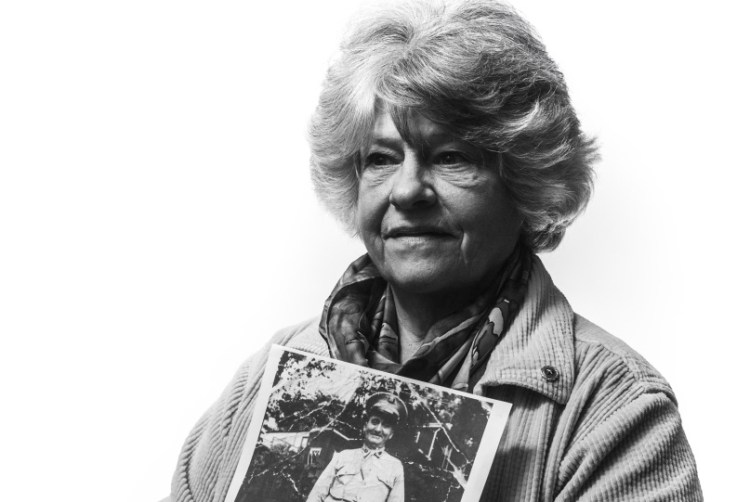

Norma Spurling of Bar Harbor at the Department of Defense’s event for MIA military members at the DoubleTree hotel in South Portland Saturday, November 14, 2015. Spurling ame to the event for her brother, Army Air Core Second Lieutenant George Hout, (cq) who went missing as he was flying supplies to China from India during World War II. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

The effort to locate and retrieve remains is a race against time as the 600-person agency works to locate and then retrieve remains from crash sites in remote locations or negotiate with hostile governments for access to burial grounds. The agency relies heavily on DNA from family members to match the DNA from bone fragments and other remains. There is little hope for recovering the 40,000 missing military members who disappeared over deep water.

“Time is not on our side,” said Michael Linnington, the agency’s director.

At Saturday’s update for families at the DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel in South Portland, government specialists explained the process of identifying and recovering remains. They also met one-on-one with families to review their case files. The agency holds seven or eight updates around the country annually for families who cannot make the trip to its offices in Washington, D.C., and Hawaii.

Even though the chances of the agency’s success decrease with every passing year, the hopes of family members of missing soldiers remain strong. During a remembrance ceremony Saturday when family members recounted the stories behind their missing soldiers, Carol Start of Georgetown urged families to stay optimistic.

Brent Granberg of New Sharon,at the Department of Defense’s event for MIA military members. Granberg’s uncle, Air Force Captain Kenneth Granberg, went missing during the Korean War. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

Clutching a photograph of Sgt. Christopher Vars, her uncle, Start told the group said she received a long-awaited sense of closure after her uncle’s bone fragments were returned to the family earlier this year.

Vars disappeared in 1950 at age 40 during the Battle at Chosin Reservoir in North Korea. Her father died without ever knowing what happened to his brother. Then in 2009, Start received a call from the Defense Department, which had received more than 200 boxes of skeletal remains from North Korea. DNA testing of family members finally led to the discovery of her uncle’s remains.

It also uncovered a missing branch of her family and a slew of cousins and other relatives she never knew existed. Start received word that her uncle’s remains had been confirmed on what would have been her father’s 107th birthday.

Last month, she and her family buried her uncle’s remains in Longwood Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

Paul Loring of Portland remembered his older brother, Maj. Charles Loring, a Maine war hero who died at age 34 leading a flight of F-80 Shooting Stars over North Korea when he deliberately dove his plane into the attacking artillery.

He received the Medal of Honor posthumously. The former Loring Air Force Base in Limestone was named after him, as was Loring Memorial Park on Munjoy Hill in Portland.

An Army Air Corps pilot in World War II, Loring spent five months as a prisoner of war after his plane was shot down over Belgium during World War II. Loring had to talk his way into the Air Force to fight in Korea, said his brother.

The U.S. military knows exactly where Loring went down. Paul Loring said he has seen the site on maps. But North Korean won’t let a search team in to look for remains.

Loring, who was scheduled to receive the latest news on the efforts to retrieve his brother on Saturday, said he didn’t expect much new information.

“Things are getting worse” with North Korea, Loring said.

Not all of those who showed up at Saturday’s forum had relatives who died in action.

James Ball of Ashland hoped to find out information about his parents, who died on a military cargo plane that disappeared en route from Chile to Argentina in August 1969. Ball said his father, Air Force Sgt. Ronnie Ball, and mother, Norma, his brother and he were living on a U.S. military base in Chile when the plane went down in some mountains. The plane has never been found.

Although the accounting agency is not be able to send out any teams to search for remains – since the agency’s mission is focused on prisoners of war and soldiers missing in action – specialists said they would share any information they come across with Ball.

Richard Wheeler of Concord, Mass., attended for his brother, a naval aviation lieutenant whose plane was likely shot down in 1953 in Korea. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

Ball, who was 9 months old when his parents died, said he doesn’t remember them. He and his brother were raised by his grandparents in Ashland. But he said he was moved by the stories he heard at Saturday’s forum.

“It is surprising, emotional,” he said.

For Spurling, the family update was a way to remember her brother, who died Sept. 24, 1944, so far away. She said at one point in her search she sent the envelopes from her brother’s letters to government specialists in hopes that his DNA could be recovered from the flaps that he licked.

No such luck, she said. But she remembers the story her mother always told her.

“The last time he was home on leave, he wanted to show me off and took me uptown. He was pretty proud of me, his little sister,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.