Norwegian energy giant Statoil has received approval to explore for oil in an area next to the Georges Bank and the entrance to the Gulf of Maine, raising environmental concerns on both sides of the border.

In a move opposed by fishermen, Canadian authorities have granted the company an exploratory lease for the area 225 miles southeast of Bar Harbor and bordering on the eastern flank of Georges Bank. Environmentalists fear drilling could leave the ecologically sensitive Gulf of Maine susceptible to a catastrophic oil spill.

It would be the closest that exploratory drilling has come to Maine since the early 1980s. Five wells were drilled on the U.S. side of Georges Bank in 1981 and 1982, before U.S. and Canadian moratoriums were put in place to protect the fishing grounds.

Final approval was granted Monday afternoon as a deadline passed for federal and provincial authorities to veto a Nov. 12 recommendation by the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board, an intergovernmental entity responsible for regulating petroleum activities near the province.

“We’re aware of concerns that exist, particularly from fisheries, about the effects of oil and gas activity,” said Kathleen Funke, the board’s spokeswoman. “Bidding on a license is a first step but doesn’t guarantee any work will take place in this underexplored area.”

Statoil has pledged to spend at least $82 million exploring the parcels under its six-year exclusive lease. The relatively small financial commitment suggests the company has no immediate plans to begin drilling, which is a much more expensive process that requires further approval. The company did not respond to interview requests.

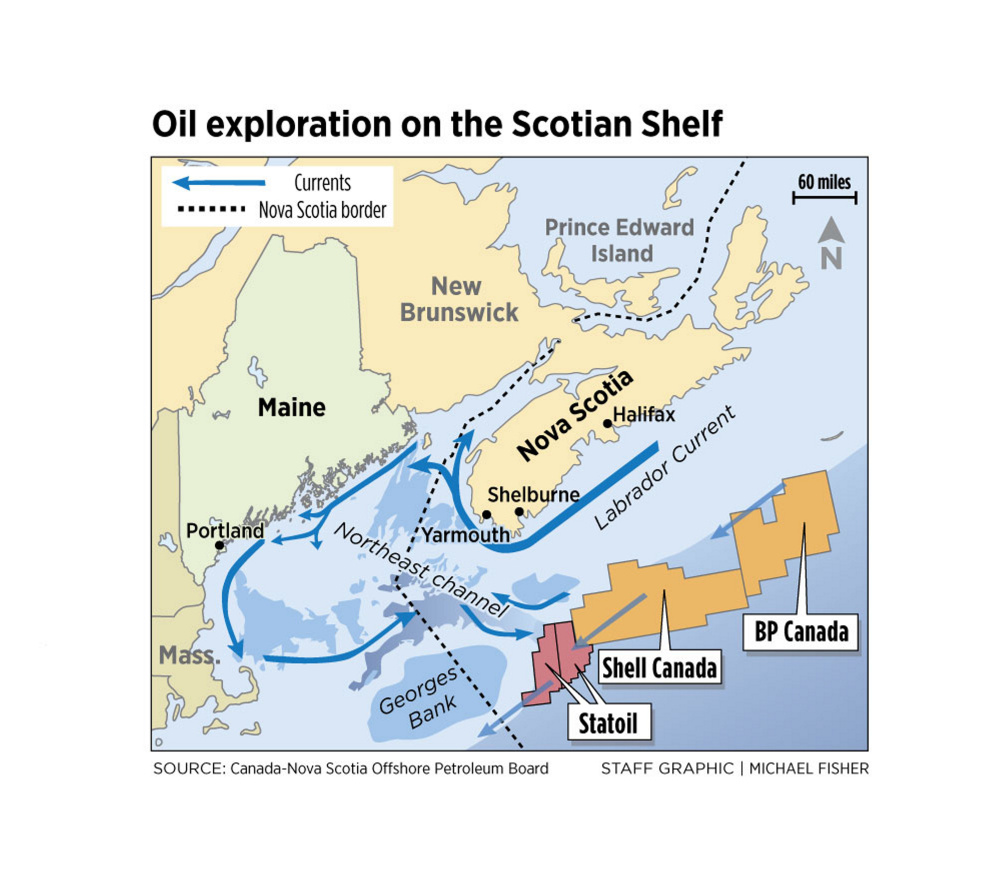

Last month, Shell Canada began drilling two wells in an area east of Statoil’s lease and has approval for five others, part of a $1.3 billion commitment. BP Canada has its own $1 billion commitment to explore another section northeast of Shell’s location and is awaiting permission to drill seven of its own wells.

Observers believe Statoil will likely confine itself to seismic testing while waiting to see whether Shell’s wells strike oil or gas deposits.

“That $82 million is just a loss leader for Statoil,” said John Davis, director of the Clean Ocean Action Committee, a Nova Scotia coalition of inshore fish harvesters opposed to the project. “They basically anted up to see what the cards will be when Shell finishes its two wells.”

Inshore fishermen in the province are unhappy with what Davis says is inadequate spill response planning. “A wellhead blowout out there would be devastating, and with the currents it could be coming your way,” he said. “The inshore fishery is distressed completely.”

Drilling in the Shell and BP parcels – which are in deeper water farther from the Gulf of Maine – likely presents less of an environmental risk to Maine because prevailing currents there likely would carry any spill away from the gulf, said Nick Record, an oceanographer at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Boothbay. (Disclosure: This reporter is a Bigelow trustee.)

The northern sections of the Statoil parcels, however, should be a subject of concern for the Gulf of Maine, Record said, because they are located at the entrance to the Northeast Channel, a 22-mile-wide deep-water channel that is the primary conduit through which ocean water enters and exits the gulf.

“Sometimes the surface water is going in one direction and the bottom water in another through the channel, and other times they’re both going in the same direction,” Record said. The variation likely results from both the seasons and the relative strength of the two main ocean currents in the area, the cold Labrador Current flowing down from the Canadian Arctic and the warm Gulf Stream flowing up from the Florida Strait.

“All of these things drive the fronts that decide if water is going in or out of the channel,” Record said. “If the spill occurred during an inflow, the water would be carried in.” If such an event occurred in summer, the damage might be contained in deep basins, but in winter – when the water is more mixed – it might be widely distributed via the gulf’s powerful circular currents.

Neal Pettigrew, professor of physical oceanography at the University of Maine in Orono, said the depth of an incident would likely be a key element. A near-surface blowout – even at Shell’s sites farther east – that resulted in oil or gas spilling in the upper 200 meters would have a fairly good chance of being pulled or blown into the Gulf of Maine system, whereas a bottom spill at 2,000 meters probably would not.

“It depends on where it comes out,” Pettigrew said. “But, yeah, you could definitely even get some of it going into the gulf.”

The ocean depth varies widely in the Statoil parcel, ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 meters.

Elizabeth MacDonald, a member of the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board’s environmental team, said a spill trajectory analysis can’t be done for the Statoil parcels until the company applies to drill at a specific site. “Without a starting point, it’s difficult to do any modeling,” she noted.

Since the first offshore well was drilled in Nova Scotian waters in 1968, 209 wells have been drilled, with two well blowout incidents: a 1984 surface blowout at a Shell exploratory gas well near Sable Island that released 70 million cubic feet of gas, and a 1985 event at a Mobil well that was contained underground, according to an April environmental assessment report on the area prepared for the petroleum board.

In order to actually drill, Statoil would have to apply for permission for each proposed well site, triggering a detailed environmental review process, said Funke, the petroleum board spokeswoman. Shell was granted permission Oct. 18 to proceed at seven wells in its lease area, while BP’s request to drill seven wells is under review. “It’s very much a possibility that the offshore petroleum board could review the (environmental assessment) and come to the determination that the proposed project could not be done without significant environmental effects,” Funke said.

Timothy Gillespie, a vocal opponent who is publisher of South Coast Today, an online news service in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, said the Statoil parcels should never have been put out to bid in the first place.

“Georges Bank is one of the most productive fisheries and fish nurseries in the entire world,” he said. “That anybody would think it was sensible to drill anywhere near Georges Bank is beyond the pale.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.