If there is one type of art I am predisposed to dislike, it is the artist’s portrait. In a nutshell, I think focusing on the individual artist as the wellspring of cultural content leads people away from understanding or enjoying art. Artists control the production and, to a certain extent, the distribution of art objects. They have much to say about their inspirations, their intentions and the craft of their objects, but it is rare that the stated intentions of an artist comprise a satisfactory summary of the content of a work of art.

What artists do not control is how we understand their work and the role it comes to play in our culture. Culture evolves in shared public space. If you see an image of a pistol in a picture of Van Gogh or in a picture of track star Jesse Owens, for example, you are likely to make very different associations, depending on how much you know about the Post-Impressionist painter’s method of suicide or starter pistols (and the African-American’s four Hitler-annoying Olympic gold medals).

I think individual artist portraits are generally misleading because they present cultural achievement in some pre-ordained Hegelian path like science: Newton leads to Faraday who leads to Edison, et cetera. Unlike science, however, culture’s steps take place out in public.

In other words, what matters about Picasso is less what he thought about his work than what others thought (and think) about it. To wit: Picasso never went abstract, but his cubist work opened the door for folks around the word to make the first abstract paintings in Western artistic culture. A century later, abstraction is generally considered “half” the story of art.

To be clear, what I think matters most about art is what the audience thinks. Artists undoubtedly play a huge role in that, as do, among others, the curators, gallerists, collectors, historians and critics, but none of those players matters more than society. Moreover, society gets to change its mind over time, long after the makers have left the conversation.

Van Gogh sold one painting during his lifetime: His work is more important to us than it was to his contemporaries.

Hanging in what is now the University of New England Art Gallery (where Van Gogh’s famed “Irises” used to hang before it became the priciest work of art ever sold) is an exhibition of artist portraits. I went out of obligation, slowed by my sea anchor of bias for art over hagiography, and was I ever I glad I went.

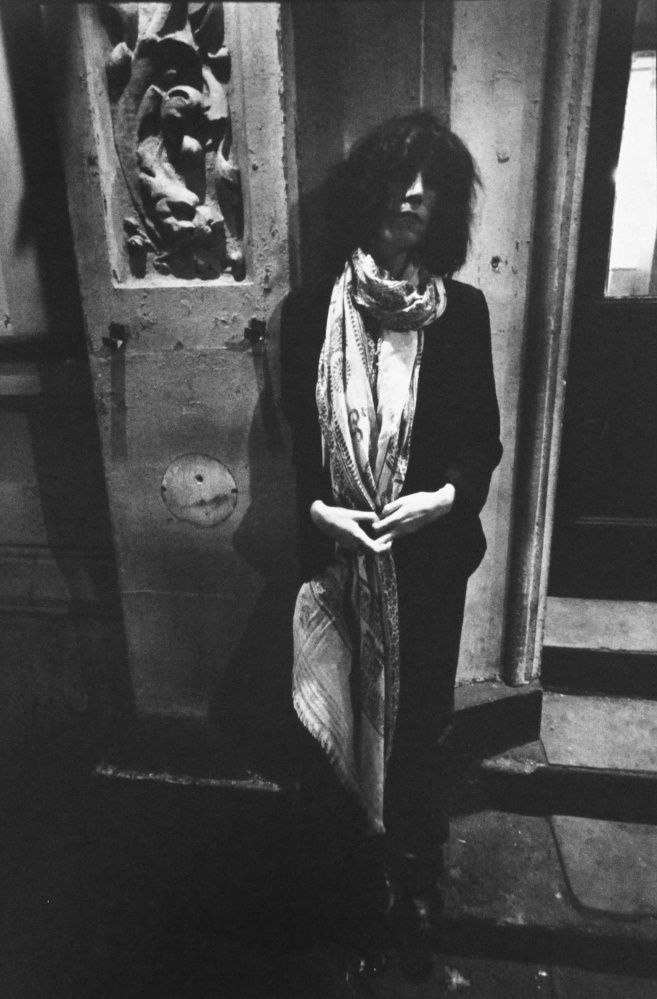

No, the exhibition did not change my mind about art celebrity and the hyper-fetishized cult of personality, but with enough excellent images of and by important artists, the show is less about personal stories than about communities and culture. The 100-plus images fill out broader ideas about Maine art and its relation to American and Western culture.

To my surprise, there are many well-known images, such as Berenice Abbott’s impressively vampiresque Max Ernst and her ubiquitous James Joyce, Peter Ralston’s gorgeously gritty Andrew Wyeth with his dog and a well-known image on the easel, George Daniell’s elfin-eared Audrey Hepburn and, among many others, Todd Webb’s suite of amazing images of Georgia O’Keeffe.

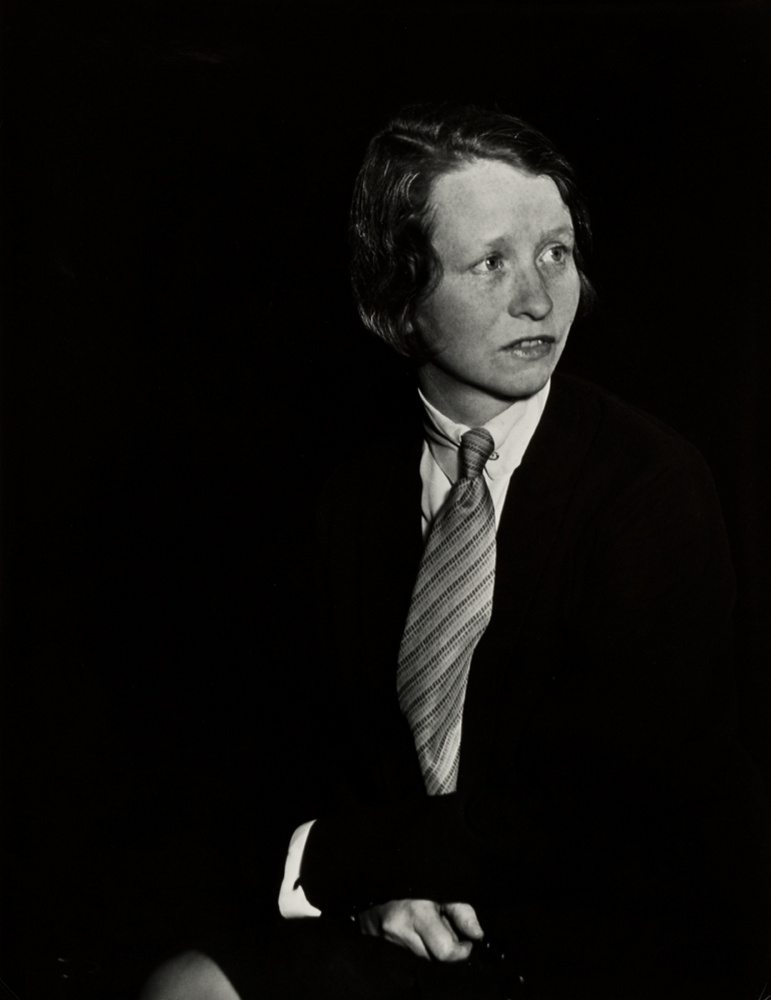

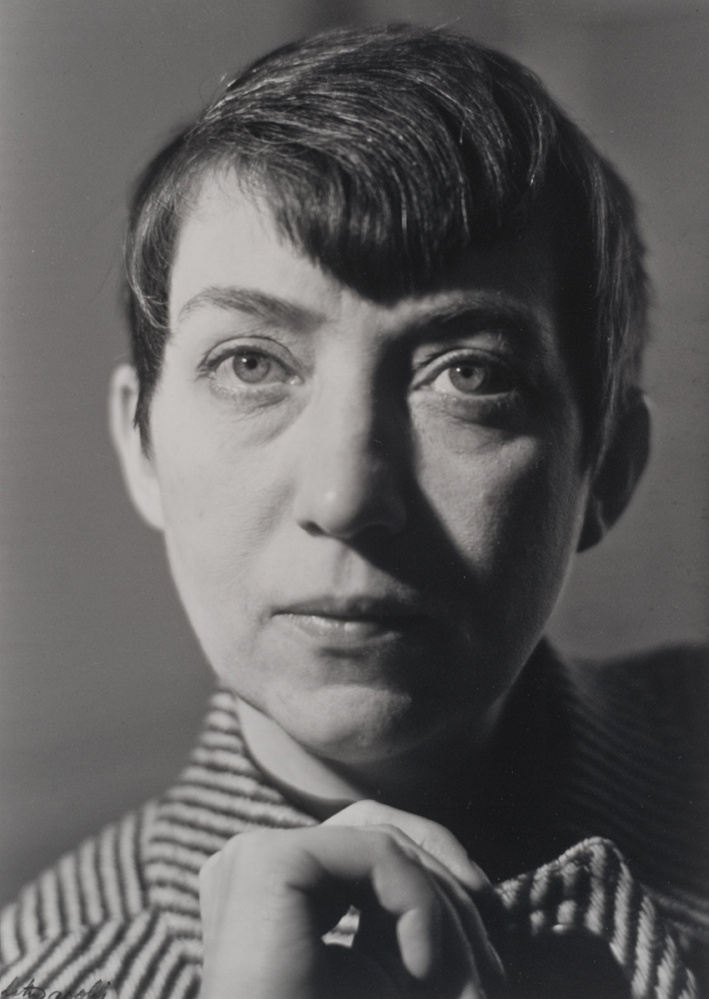

Certain artists bubble up to the fore, an idea pleasantly set into motion by a pair of contrasting portraits of Joyce that greet the entering audience. It’s also a pleasant surprise to get to see eyes that are usually behind the lens, like those of Ansel Adams and Elliot Porter, but among scores of powerful images, you come out with the idea that Berenice Abbott, oval and imperious-eyed, wasn’t just a world-renowned figure, but the doyenne of Maine’s photographic culture.

Abbott’s appearing again-and-again also gives an outward shape to Maine’s pictorial culture, a powerful and important idea that rarely takes such clear form. It is a reminder that we Mainers often underestimate our major players as they take their seats on the international stage. Abbott, for us, is too often a woman of Paris, Man Ray and Atget rather than the lady of Monson, Maine. And, conversely, we get to sense our own provincial perspectives about cultural players who, by dint of a broader audience, are bigger than we have been able to see from our ringside seats in the vernacular theater.

Arnold Newman was unquestionably one of the great photographers of artists, and his 1941 image of Yasuo Kuniyoshi alone is worth the visit. The Maine-connected Kuniyoshi was one of America’s best known artists at the time, but his name was essentially erased by our societal response to the events that followed Dec. 7 of that year. Reading that date hit me like a tsunami. Because of his heritage, Kuniyoshi was imprisoned in a concentration camp and we, likewise, razed his reputation.

Most of the conjured stories, however, are more comfortably closer to home. Jack Montgomery is an active local artist, and his 2010 image of then 99-year-old Will Barnet is inspiring and powerful. David Etnier’s portrait of Tom Crotty, who died this year, impressively captures the crisp and curt textures of the artist and art dealer’s personal presence. And Etnier’s 1993 image of Brett Bigee preternaturally captures the painter’s perfect posture – the very thing, as well, of his art. And within this impressive context, it becomes easy to enjoy, for example, the theatrically fussbudget repose of the pouting Robert Indiana splayed dramatically on his Vinalhaven couch in 1984.

It is, after all, not the personalities of the artists that ultimately matter to our culture, but, rather, how they personally feed the flow of the river-broad currents of culture. While this topic of context is rightly given lip service in practically every monograph and retrospective, the society-oriented view of culture is a very hard thing to see during an exhibition precisely because post-war Americans too often default (wrongly) to the perspective of the individual artist rather than respecting our own privileged position as the pan-perspective audience. (And, again, culture doesn’t happen in the lone artist’s studio but, rather, in the minds of the broader public.) By successfully delivering this rare experience, “Portraits of the Artist” accomplishes something impressive.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.