Tanya Fletcher’s “Coming of Age” at Ocean House in Cape Elizabeth is a small show in numbers only, with four paintings and eight drawings.

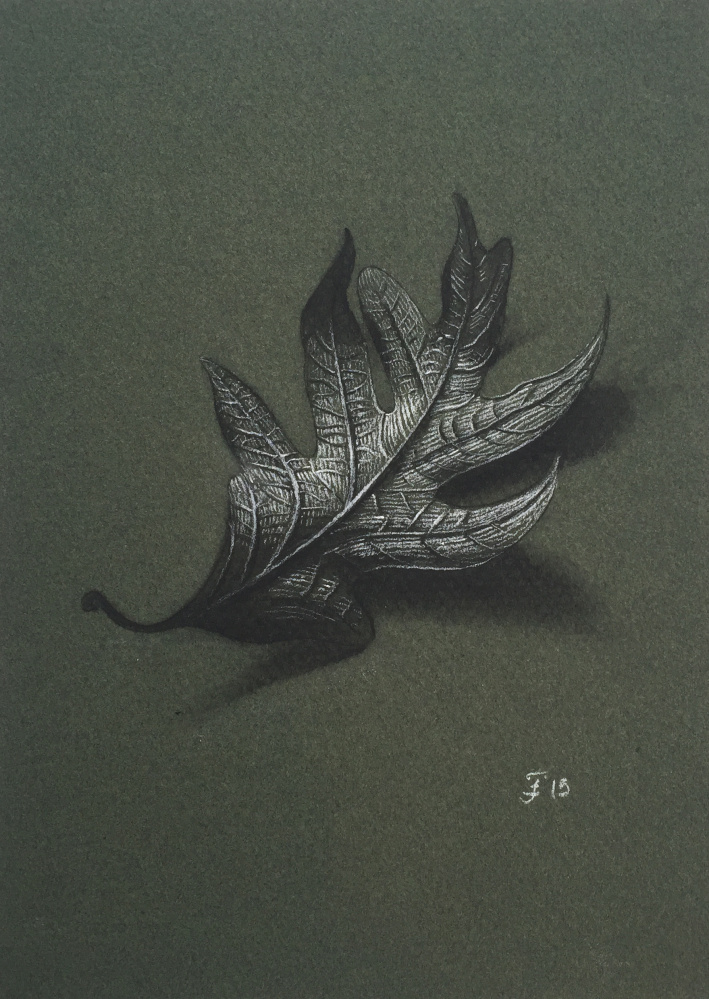

Each drawing features a single oak leaf in white and black charcoal on moss green or burnt orange paper. Quite simply, these are old-master-style drawings, bold and clear and rendered with a startlingly crisp efficiency.

“The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face” is typical of the titles, song references that take you from Foreigner to Chicago and back. At first I found these a little distracting, because they seemed nostalgic and unrelated to the content of the work, but after spending a few minutes trying to place the sense of era, it became clear that time passages comprise a serious topic for Fletcher and that the songs marked seasons (or episodes) of her life. This is how I personally experienced them, and by reaching out to broadly shared public experiences – like popular (but good) songs – Fletcher rather elegantly ties the personal to the societal. Instead of limiting the effect to individual nostalgia, Fletcher opens the door to something broader.

The metaphors might seem simple (fallen leaves, autumn, old-master style, classic songs and so on) but together they weave themselves into a rich and rigorous fabric. The old-master technique even works alone: Fletcher’s old-school approach of white and dark charcoal on mid-toned paper makes it easy for us to consider her chops critically. This makes it clear that she respects her audience and helps us tie her formidable technical abilities to the conceptual content of her decorative aesthetic. With her nod to the northern Renaissance feel of Albrecht Durer or Hendrick Goltzius, it’s hard to ignore the “memento mori” reading of the images – the reminder of one’s own mortality that was such a common (and meaningful) theme in Western visual art.

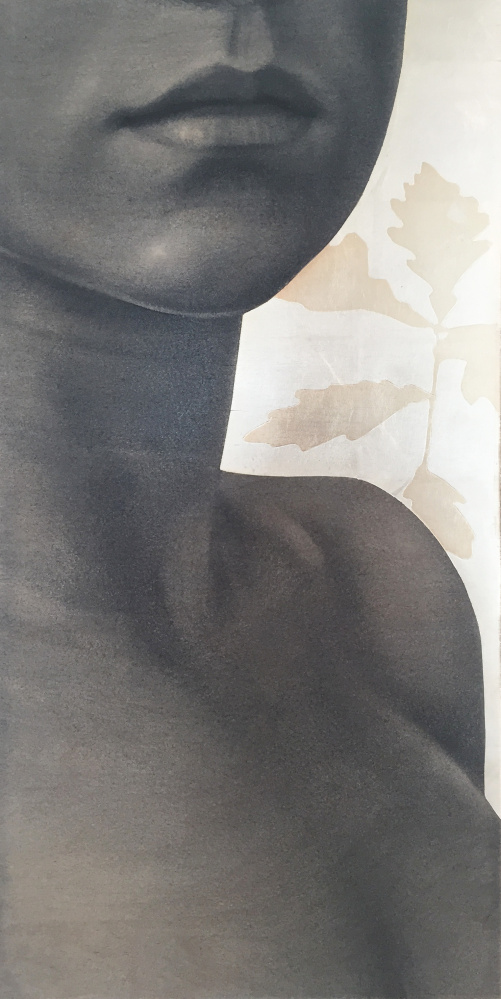

But the most potent force of “Coming of Age” arrives with the four paintings. Each shows the upper torsos of a female figure to just above her lips. The unclothed figures are painted by a monochrome, subtractive technique in which a great deal of wet, dark paint is put on the panel and then removed to reveal the lighter passages. (It’s the painterly equivalent of carving a sculpture from a block of stone.)

To the right and left of the figures on the horizontal panels are flat areas on which a floral element in untreated silver leaf has been laid out and incised. This reinforces Fletcher’s age and aging content: The floral forms will darken over time as the exposed silver naturally tarnishes.

The figures depict young, trim and healthy women. There are just a few salient indicators of age, but without individual identifiers or facial features, these become important. All have full lips, but the slightly less wide mouth of one gives her the youngest appearance. Another’s chest swells subtly at the very top of a relatively larger breast. Another has the vaguest hint of a wrinkle on her neck.

As it turns out, the models are Fletcher’s nieces. This might not resonate to the casual viewer only encountering these images, but in the context of Fletcher’s work over the past few years, this adds depth and insight to her developing content. Previously, Fletcher had used her sister and herself as models, and the eminently physical and deeply personal but very light touch of her figures is, to say the least, an uncommon sensibility for paintings of nudes.

The history of nudes in Western art is essentially a seesaw that has academic training on one side and sexuality on the other – even if camouflaged as metaphor or myth. Fletcher’s observant approach to the nude is intelligent and fresh. She doesn’t turn away from female beauty or attractiveness, but she also doesn’t use it as sexualized bait or a bull’s-eye target for the objectifying male gaze. While she doesn’t rely on personal narratives (like what I am conveying about her and her family) for the viewer experience she creates, knowing the story in this case helps reveal a sophisticated and nuanced drive behind Fletcher’s ever-developing conceptualism.

Female beauty in Fletcher’s hands takes on a nurturing and honest (though surprisingly impersonal) cast. And its elements feel pleasantly organic and spare, most notably when she incorporates the wood grain of the panel. With the subtractive technique, the lightest parts of the painting occur when the artist removes the most paint – which gets her down to the grain of the birch panel that then doubles its natural textures both as the painting support and the touch-textured skin of the figures.

Fletcher unapologetically equates the decorative with the beautiful, the organically natural (the element silver, smooth-finished wood grain, plant shapes, human form, etc.) and femaleness. This is a very quiet and subtle set of qualities that, to me, feels like the gaze more concerned with caring and accurate observation than, say the cold painterliness of Philip Pearlstein or the uncomfortably penetrating gaze of Lucien Freud.

Instead, Fletcher equates bodies with people. This, too, is how her sense of time comes into view. Those classic song titles elicit seasons past, but seasons in which seeds were planted to begin their development into the vibrant communities growing around us.

It is through these textures that Fletcher avoids (possibly unintentionally) nostalgia and replaces the space of memory with something thriving, organic and very much alive in the present. You could take the idea of the silver leaf’s tarnishing process and imagine something’s aging, but a more satisfying reading is that Fletcher has considered the future and set up expectations with the understanding that the painting is intended to change – and that all she could do is set it in motion and let it follow its own course from there (which rather matches a parental touch).

Fletcher’s leaves are seeds of a sort. They look like hands. They have passed their age of being useful and yet we easily see they have been part of that (family) tree. And while their style reaches back, they remind us of experience and the idea that to have something old or dated, you must be able to distinguish the present from the past in what must be described as an analytical moment. And that analytical moment of awareness, Fletcher hints, is a useful model for understanding not only history but humanity as well.

“Coming of Age” may be a little show, but it does enormously well with some very big ideas.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.