Managers of the Maine Public Employees Retirement System have been keeping a close eye on the flagging stock market in recent weeks, but they say the system that provides pensions to thousands of former teachers, judges, lawmakers and other state and municipal workers remains strong.

The most recent data available for the $12.7 billion retirement system, known as MainePERS, back up that assertion. As of June 30, its funding ratio had reached an all-time high of 83.6 percent, making it one of the best-funded public retirement systems in the nation.

Still, challenges lie ahead for MainePERS. As Maine’s workforce ages, its financial obligations are bound to increase. In the 2015 fiscal year – a lackluster year for investors – the retirement system paid out $300 million more in benefits than it took in through contributions. Contributions totaled $545 million, and benefit payments totaled $851 million.

And there is always the possibility of another recession like the one in 2008 that knocked the funding level down to roughly 70 percent. Jittery stock markets – the Dow was down 8.33 percent year to date on Friday – are adding to investor anxiety.

Still, MainePERS administrators say they have a powerful weapon in their arsenal to fight against unfunded liability creep: a constitutional amendment passed in 1995 that requires the system to be 100 percent funded by 2028. It also prohibits the creation of new unfunded liabilities.

With that amendment in place, the retirement system has rebounded heartily from an all-time-low funding ratio of 28 percent in the 1980s, MainePERS Executive Director Sandy Matheson said.

“There clearly were years when the state didn’t pay into the fund,” she said. “You can’t get to 28 percent any other way.”

Established in the 1940s, the pension fund had been neglected for decades, eventually becoming the subject of two blue ribbon commissions and drawing plenty of political controversy through the years. In the early 1990s, then-Gov. John McKernan and the Legislature reduced benefits to retirees and then borrowed from the fund to fill a budget hole. In 2005, then-Gov. John Baldacci suggested borrowing $250 million from it to balance the budget and then pay it back through future lottery revenue.

The fund benefited from a 2011 overhaul and has been on solid footing since, say its managers.

Several other state retirement systems have reached a crisis point in recent years, according to a report issued in July by the Pew Charitable Trusts. The worst-funded plan is in Kentucky, where unfunded liabilities climbed to more than $10 billion in 2015. The Kentucky system has a funding ratio of about 19 percent, meaning it only has 19 percent of the assets it needs to meet all of its obligations to pension recipients over the next 30 years.

Pew ranked Maine’s retirement system 15th-best in the U.S. in terms of its funding ratio, and said it was one of only 19 state systems paying at least 100 percent of recommended contributions annually as of 2014.

As Maine’s workforce continues to age, more baby boomers will be drawing pensions, which will inevitably increase the system’s costs. Almost 17 percent of the state’s 11,568 executive branch employees are 60 or older, according to state data. However, Matheson said it’s impossible to predict how many members will retire in the next five years, because many are choosing to continue their careers later in life.

“An increasing number of people are working beyond their normal retirement age,” she said.

As long as employers in the MainePERS system continue to make the required contributions, a downturn in the stock market will not prevent anyone from receiving his or her pension, Matheson said.

“We consider our biggest risk to be contribution volatility,” she said. “Markets today, they are what they are. We have found that our greatest return happens when we don’t react to the market.”

Not a free plan

The pension funds administered by MainePERS cover more than 100,000 current, former and retired government employees, including teachers, judges, legislators and state and municipal workers. More than 80,000 belong to the largest fund, for state employees and teachers. About half are active employees, and the other half have either retired or moved on to other jobs.

As with a 401(k), every employee pays into the fund each pay period, and the employer matches a certain percentage. The matching amount, funded by taxes, varies from year to year, depending on the system’s funding needs. Currently, employees cover roughly two-thirds of their total contribution, which is about 12 percent of payroll, Matheson said.

However, unlike a 401(k), the amount a retired employee receives is fixed, and is not based on market performance. Another difference is that for MainePERS members, the retirement system replaces Social Security – they don’t pay or receive both.

Because the benefits are fixed, and the employers are mandated to cover all liabilities, poorly performing investments raise the taxpayer cost of the retirement system.

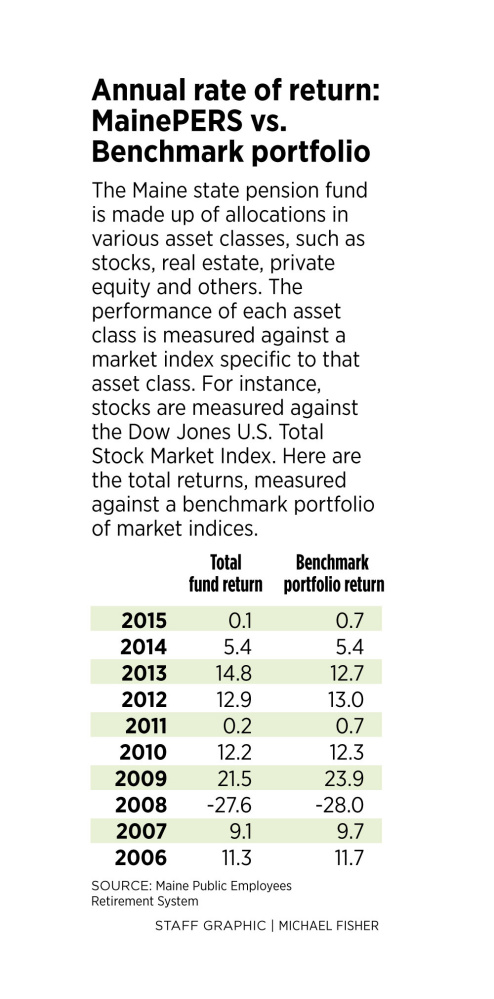

However, annual gains and losses are not applied to the formula immediately. MainePERS spreads them out over a three-year period using a process called “smoothing.” A bad year followed by an equally good year requires little overall change to the contribution requirements. The worst investment year for MainePERS in the past decade was 2009, when the funds lost nearly 19 percent of their value. However, it was followed by an 11 percent gain in 2010, and a 22 percent gain in 2011.

Also in 2011, Maine lawmakers passed a bill that reduced the overall cost of the retirement system by raising the retirement age from 62 to 65 and reducing the cap on annual cost-of-living increases from 4 percent to 3 percent.

Peter Mills, a former Republican legislator who now oversees the Maine Turnpike Authority, credited Gov. Paul LePage for pushing through the changes, which helped MainePERS recover quickly from losses tied to the recession.

“LePage, for all his shortcomings, at least did cut back on the benefits side to reduce the future liabilities of the system,” he said.

Strategy matters

State retirement systems are constantly liquidating investments to pay out benefits to retirees while taking in and investing new contributions.

MainePERS has developed an investment strategy that recognizes and adjusts to market trends without reacting to short-term market gains and losses, said the system’s chief investment officer, Andrew Sawyer.

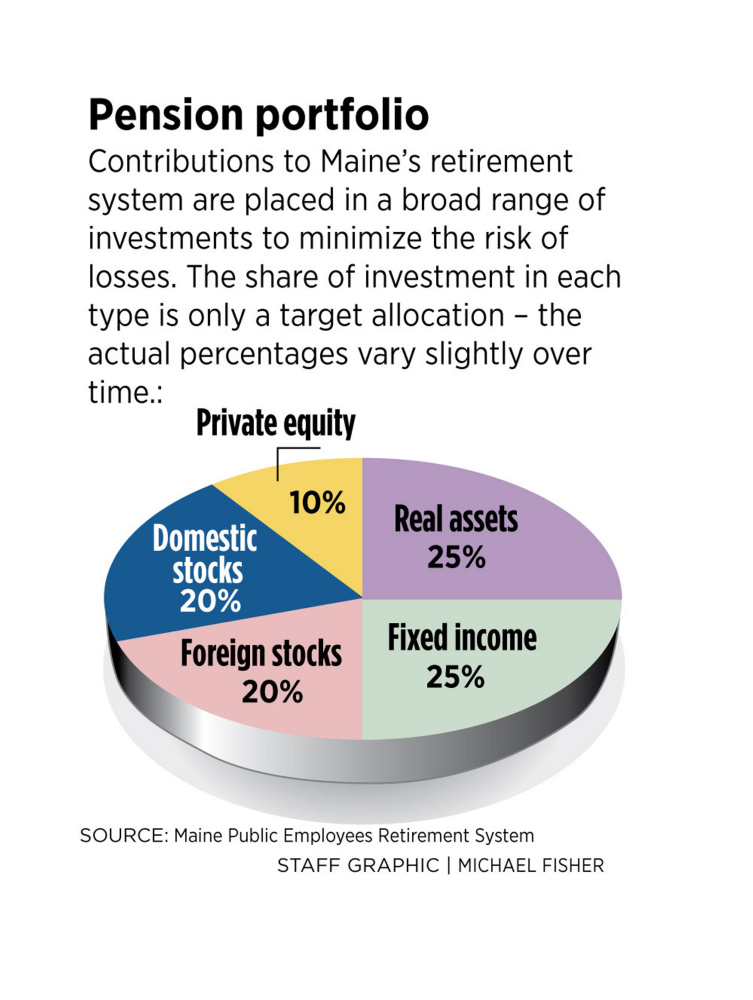

About 65 percent of contributions are invested in stocks and bonds, 25 percent in real estate and infrastructure and another 10 percent in private equity, he said. The system’s administrators and trustees adhere to a passive strategy that relies on index funds that track closely with the market’s overall performance, while investing in other vehicles such as bonds and real estate to hedge against market losses.

“The basic belief is that the markets are generally efficient,” Sawyer said. “We don’t choose General Motors over Ford, or say that automobile companies are bad and retailers are good. We own the market.”

Another thing the fund’s administrators don’t do is attempt to “time the market,” he said. In other words, they don’t buy and sell stocks or funds based on a belief that they are about to increase or decrease in value. Attempts to time the market frequently backfire, Sawyer said.

“The most basic principle in investing is to buy something when it’s cheap and sell it when it’s expensive. Many investors do the exact opposite of that,” he said. “We believe that having a long-term strategy and sticking with it is the best approach.”

The retirement system has achieved an average annual rate of return of 6.6 percent over the past decade, which included the Great Recession. By comparison, the S&P 500 index had a 6.5 percent average annual rate of return during the same period.

Sawyer said the system’s administrators and trustees are not going after aggressive gains, because that would increase the chance of precipitous losses.

They are constantly focused on mitigating risks. Sometimes they sit around for hours thinking of things that could potentially hurt their investment, he said.

“A solar flare taking out a power grid – that’s actually on the list.”

J. Craig Anderson can be contacted at 791-6390 or at:

Twitter: jcraiganderson

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.