Sediment samples collected from behind Yarmouth’s Bridge Street dam contained elevated levels of mercury and other contaminants, a factor likely to influence discussions about improving fish passage now that town officials have balked at removing the historic Royal River dam.

After pushing for years to remove the two lower dams on the river, conservation groups have shifted their focus toward improving the fishways that allow migratory fish to swim around the structures. As part of that exploration, The Nature Conservancy recently paid a consultant to collect sediment samples behind the Bridge Street dam in order to assess potential contamination.

One of 10 sediment samples collected just upstream from the Bridge Street dam contained elevated levels of mercury, while six of 10 samples contained elevated levels of organic compounds linked to industrial activity. While not surprising given the river’s industrial past, the findings will become part of the dialogue with downriver marina owners and Yarmouth residents about the next steps in improving the fishway at the Bridge Street dam.

“We will be following this issue quite closely,” said Alan Stearns, executive director of the Royal River Conservation Trust. “This is the second sampling that found toxics in the river.”

MANUFACTURING LEGACY

Jeremy Bell, aquatic habitat restoration manger for The Nature Conservancy, said it is common to find contaminants in sediments in New England rivers because of the region’s legacy of manufacturing.

Bell said he expected to receive a briefing next week from the consulting firm Stantec to better understand the test results and begin discussing potential next steps, including whether additional sampling is warranted. The Nature Conservancy has also offered to pay for a Stantec representative to brief members of the Yarmouth Town Council on the findings.

“There are a lot of questions about the meaning of the contamination, but the levels are higher than expected,” Bell said.

Construction of a new fish passage system could stir up some of that sediment, or a new fishway could change the hydro-dynamics of the water behind the dam in a way that sends some sediment downstream. Bell said The Nature Conservancy and its partners hope the sediment testing will provide scientific data to help inform the broader community discussion about ways to improve fish passage at the site.

“It’s a community space and a community response,” Bell said. “I would love for it to be a collaborative process with everyone working toward the same goal.”

Parts of the Royal have been dammed since the 1700s as industries ranging from lumber and paper mills to tanneries and fish-processing plants sought to harness the power of the river. But while the above-ground evidence of many of those industries is gone, some of those factories left behind a legacy in contaminated soils and river muck.

DAM REMOVAL OFF THE TABLE

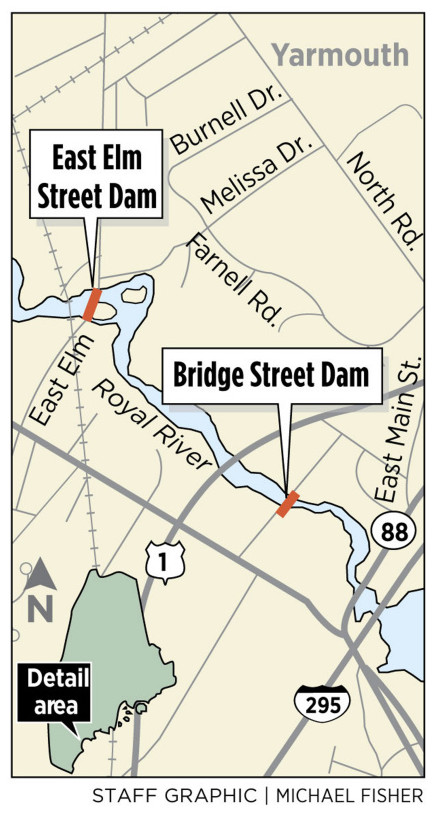

After years of sometimes heated discussion in the community, members of the Yarmouth Town Council agreed in September to stop discussing the possibility of removing the Bridge Street dam as well as the East Elm Street Dam farther upriver.

Critics worried that removing the Bridge Street dam would stir up contaminated sediments that would then flow downstream. The town’s several marinas, which depend on periodic dredging to keep the harbor navigable, raised concerns about over-siltation of Yarmouth’s scenic harbor if the dam was no longer in place. Other town residents, meanwhile, raised concerns about the loss of the lake-like appearance of the river near the downtown area.

Yarmouth Town Manager Nat Tupper said the Town Council officially disengaged itself from the debate.

“It was clear that we are not going to do dam removal,” Tupper said. “In their discussion, they said that if others want to continue looking into it, that’s fine … but the town has kept out of it since.”

Since the council decision, groups such as The Nature Conservancy, Maine Rivers and the Royal River Conservation Trust have shifted their focus toward improving the fishways installed at the two dams during the 1970s. Species such as alewives, eels and American shad migrate up and down Maine’s coastal rivers, but the groups contend the Bridge Street fish ladder is functional only part of the time and the Elm Street dam’s fishway is even more inadequate.

Deborah Delp, president of Yankee Marina and Boatyard, said the marina community is “absolutely supportive” of improving upstream fish passage around the dams, although she said it is important to recognize that no fishway will ever be 100 percent effective for all species.

“I think there is a lot we can do that meets the needs of the whole community,” Delp said. “We can help the fish, do hydropower (at the site) and protect the marinas.”

HYDROELECTRIC INVESTMENT

Indeed, there has been renewed interest of late in tapping into the hydroelectric potential of the Royal River in downtown Yarmouth.

In a memo to town councilors this month, Tupper wrote that a company, Progression Energy, continues to investigate the possibility of leasing the hydroelectric facilities located in Sparhawk Mill just upstream from the Bridge Street dam and investing in the facility to increase power generation.

“New investment in the hydroelectric facility need not exclude work and considerations to improve fish passage,” Tupper wrote.

Stearns with Royal River Conservation Trust said his organization is committed to improving fish passage but also addressing concerns about contaminants in the river, in a transparent and collaborative approach. In a recent email to Tupper, however, Stearns raised concerns that the community and organizations such as his became “consciously lax regarding attention to fish passage” amid the yearslong focus on dam removal.

Stearns urged town officials to communicate openly about discussions of changes to the hydroelectric facility and about fish passage opportunities.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.