As Portland has blossomed into one of America’s top restaurant towns, its reputation as Maine’s leading art town has been shaken.

Rockland has bloomed with new galleries and the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s new building in that town is on schedule to open in June. Several popular Portland gallery spaces, including A Fine Thing and Aucocisco, have closed, so the professional gallery scene – particularly from a contemporary art perspective – feels much reduced.

Whether it is actually reduced, however, is a matter of perspective. The Portland Museum of Art, SPACE Gallery, Susan Maasch Fine Arts and the Maine College of Art have been expanding their exhibition spaces. Art House owners divided to add the winsome little Ocean House Gallery in South Portland. On Congress Street in Portland, the UMVA gallery and She-Bear (which recently featured an excellent Tom Curry pastel show), appear to be finding their sea legs.

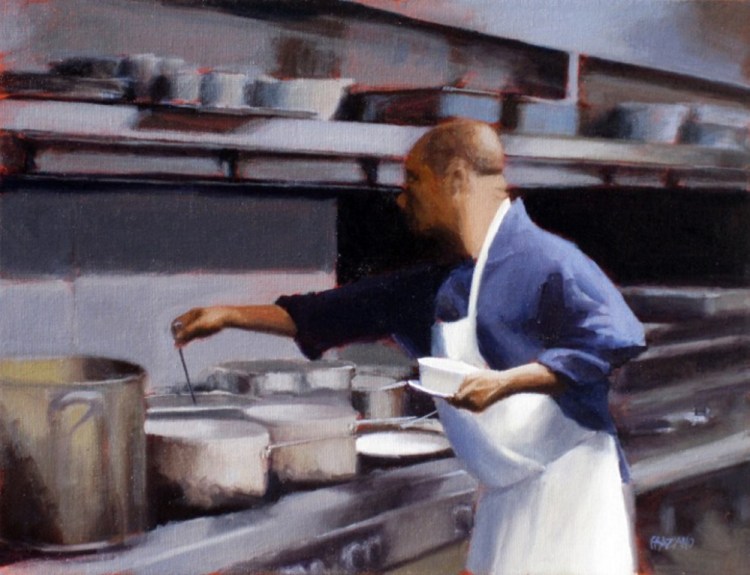

Roux & Cyr is a newish gallery on Free Street that has been flying somewhat under the radar because it features traditional representational painting and generally doesn’t look to well-known locals. It now has an excellent exhibition of Dan Graziano’s paintings of Portland restaurant workers along with photographs by Michael McAllister of the same subject.

Graziano’s “Dining” features about 20 canvases. It’s easy to see these as conservatively traditional paintings; after all, they feature interior restaurant scenes in a style reminiscent of 19th-century Paris. But such lazy viewing may lead you to miss a great deal of interesting – and still ongoing – shifts in American painting. Graziano’s work evidences an East Coast shift to further incorporate the Bay Area Figurative Movement: More regional painters are looking to the luxuriously worked surfaces of Diebenkorn, Oliveira and their kith.

This is particularly important in a place like Maine, where we have such deep painterly traditions – so deep, in fact, that they often now appear as cliché. (I recently visited the Portland Museum of Art’s handsome works on paper show with an artist who complained about Hopper’s lighthouse watercolor as “cliché.” It wasn’t cliché when Hopper painted it; rather, it was the popularity of his work that created that perception.)

While the easy route is to liken Graziano’s work to earlier brushy-bravado, made-in-France models or to contrast it with Hopper’s Maine-frugal paint application, his work is better revealed by comparing it to the Bay Area-seasoned Maine painter George Lloyd, Boston-based Ben Aronson, who blends Maine legacy into a thick palette of Bay Area style, or the late Alfred Chadbourne, who brought his time in France and California back to Maine in a savvy but brushy way.

In other words, Graziano wields a bold but sophisticated brush. Many are too quick to conflate this type of quick-brush realism with overly commercial work, but it takes skill and observational intelligence, which Graziano has in spades. What he does particularly well, in addition to handling the brush and the light-oriented coloration generally associated with French painting, is present figures in compelling gestures. We see this as a blending of sculptural qualities and narrative action in Graziano’s best works.

Three of the strongest images share a central figure behind a work counter facing right to left. The action varies in terms of balance, dynamics, motion and urgency. A cook stands stolidly upright in a sober, controlled pose as he flicks a sauté pan next to a solid cylinder of flame that rises as high as his head. A saucier reaches his full arm’s length straight out only to tilt his ladle with deft urgency back towards him. Another elegantly decisive chef reaches with the lean athletic sweep of a tennis pro towards a lower oven below our sight line.

What makes this last image particularly successful is the combination of the figure’s gesture and the bold flash of the painter’s brush as he whisks along the upper highlights of the chef’s white jersey: It is great impasto. Less obvious but no less important is Graziano’s ability to be understated; the background objects are subtly softened so that our eye moves to more contrasting and decisive passages.

Graziano has the chops to be economical with the figures’ faces so that they are compelling but also not overly individualized. And this essentialized approach gives a graceful and professional feel for the culture of Portland restaurant kitchens, rather than a sense of the specific individual portrait.

The face of the soup cook, for example, directs us to the subject of his attention – the pot whose contents are being served – rather than to him. While the man’s face is in low-contrast shadow, a highlight on his thumb throws his hand into sculptural relief and therefore draws our focus.

A baker’s arms defy symmetry to offer a pulsing work rhythm. A waiter serves us in a bistro space; and we are placed there by our seated, table-height view. The server looks away, like all of Graziano’s subjects, which allows us to regard the scene unselfconsciously so that our gaze is free to scoot about or linger at will.

These figures have the grace of well-practiced dancers, but their lack of presentational theatricality gives them the feel of Degas’ off-stage dancers who are not under the glow of lights and the eyes of eager viewers.

McAllister’s photos serve to underscore the success of Graziano’s paintings, but the comparison does not bode well for the photographer. While Graziano uses contrast, light and focus to shape his compelling backstage narratives, McAllister’s photos treat the kitchens like a stage and then wind up with either artifice or a lack of choreography.

A portrait of Harding Lee Smith (who is certainly handsome enough) and a bar set with oysters feel like staged marketing collateral.

“Potato” tries to succeed with an exciting central cook flame when all around it are awkward aspects: burned out and blurred pepper mills too loud with the inconsistent light of a camera flash, an inelegant figure obliviously turned away from the main action and so on.

McAllister gets stuck between well-measured photography and snapshots while a heavy tilt in either direction would have served him much better. Focusing on the flash could have delivered instantaneity. Slower high-focus shots could have evened the temperature of the light and let blurred actions showcase the urgency of the cooks’ gestures.

Even though McAllister does not particularly benefit by sitting across the table from Graziano, their works are more revealing together. They effectively showcase the kitchen culture of Portland eateries while introducing notable distinctions between painting and photography.

And while there are some flaws in Graziano’s approach (details like an eyebrow, apron straps and so on can feel overly considered and after the fact), even parsing these makes the case for the role of decision making and problem solving in traditional representational painting.

The result is a fresh case for the old school’s ability to comment insightfully on contemporary culture: Where there is action, there is narrative, and representational painting has spent a lot of time honing its chops on storytelling.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.