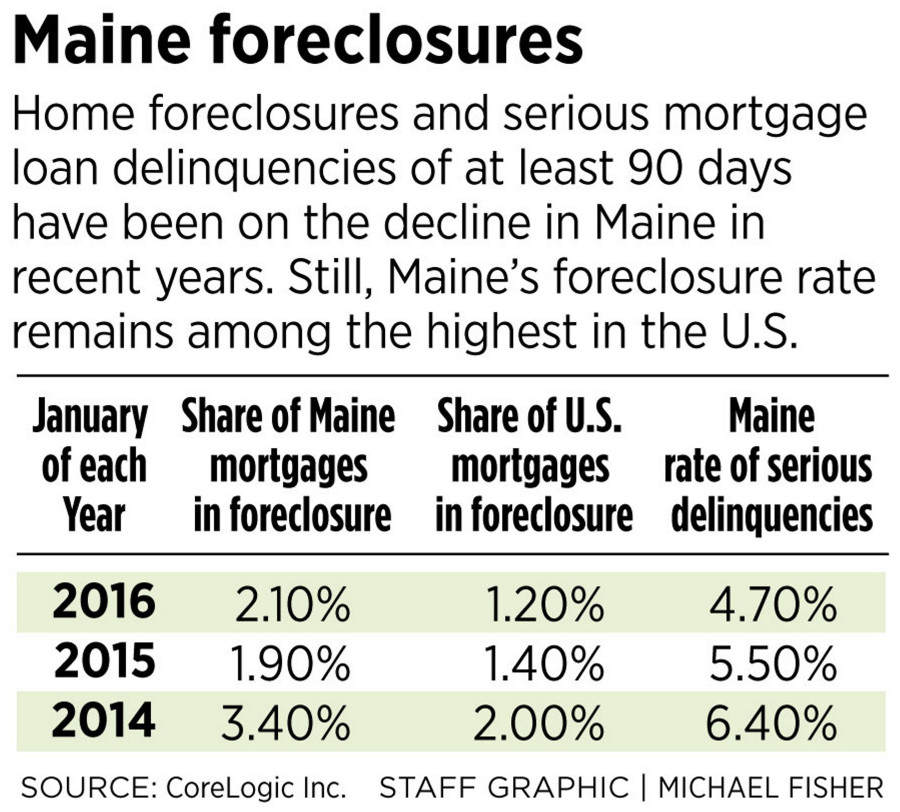

Maine’s home foreclosure inventory – the share of all mortgages in some stage of foreclosure – remains among the highest in the nation despite a significant drop in completed foreclosures from the previous year.

Maine’s foreclosure inventory was 2.1 percent in January, seventh-highest among the 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to a report from CoreLogic Inc., a financial analysis firm based in Irvine, California. The national average was 1.2 percent in January, the report said.

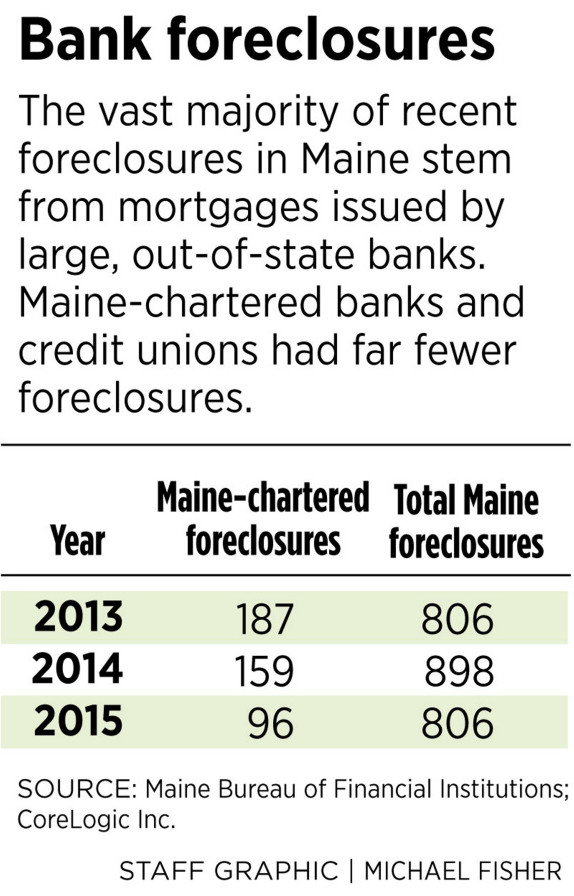

More than 800 Maine homes were lost to foreclosure in 2015, down from nearly 900 homes in 2014, according to CoreLogic. Nearly 100 of the Maine foreclosures completed in 2015 stemmed from loans issued by Maine-chartered banks and credit unions, while more than 700 were from loans issued by federally chartered financial institutions, according to CoreLogic and a separate report issued in February by the state Bureau of Financial Institutions.

In addition to their devastating effect on homeowners, foreclosures are bad for the economy because they can drag down home prices and in some cases lead to neighborhood blight.

Not every foreclosure process ends in home repossession. In many cases, the lender agrees to a “short sale,” allowing the borrower to sell the home for less than the loan balance due, with the bank usually absorbing the remaining debt. In a smaller number of cases, the borrower renegotiates the loan terms or catches up on past-due payments and keeps the home.

JUDICIAL PROCESS MAKES INVENTORIES LINGER

Maine is one of 22 states that require a judicial process for all home foreclosures. It takes far longer in these states for a lender to complete the foreclosure process, because the courts encourage borrower and bank mediation and require evidence of a loan default before they will allow the foreclosure to proceed. As a result, many states with a judicial process are still working through the spike in foreclosures that began in 2008 after the collapse of the subprime lending market.

States with non-judicial processes worked through their housing-crash foreclosures far more quickly, with millions losing their homes over a few years.

As of January, nine of the 10 states with the highest remaining foreclosure inventories were judicial foreclosure states, led by New Jersey (4.3 percent), New York (3.5 percent), Hawaii (2.4 percent) and Florida (2.3 percent). Washington, D.C., which has non-judicial foreclosure, was fifth-highest with 2.3 percent.

There are additional factors that have kept Maine’s foreclosure inventory higher than in other states, said William Lund, superintendent of the Maine Bureau of Consumer Credit Protection. One reason is that a relatively large percentage of Mainers own homes compared with other states, he said.

“Maine’s population is relatively stable, and many Mainers owned their own homes, so when the recession hit, our population was affected to a greater extent than residents of those states where renting or leasing is the norm and ownership is more rare,” Lund said.

According to U.S. Census Bureau data, Maine had the nation’s ninth-highest homeownership rate in the fourth quarter of 2015, with 70.9 percent of all homes owned by their occupants. The national average for the same period was 63.8 percent. In the fourth quarter of 2006, Maine’s homeownership rate was fifth-highest in the U.S. at 75.5 percent when the national average was 68.9 percent.

Another delay stems from unresolved legal questions in Maine courts about foreclosures initiated by a third party known as Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems on behalf of investors in mortgage-backed securities, he said.

“Lawyers who represent out-of-state lenders tell us there is a backlog of cases in their offices awaiting resolution of the legal issues before foreclosures are initiated,” Lund said.

Maine consumer protection officials don’t know how the state’s current foreclosure rate compares with pre-recession levels because they didn’t track it before the recession, he said. However, Lund said it has at least fallen back to mid-2009 levels.

IMPACT LOW IN CUMBERLAND COUNTY

Portland residential real estate broker Michael Sosnowski said that, at least in Cumberland County where he operates, foreclosure sales have dwindled to the point where they are no longer dragging down home values overall.

During the past six months, there were 775 houses and condominiums sold in the county, of which 67 were bank-owned or short sales, said Sosnowski, of Maine Home Connection. Among the 417 homes currently listed for sale in Cumberland County, only 22 are designated as bank-owned – less than 5 percent of all listings.

“As you can see, there has been a steady decline in the amount of foreclosure-type properties,” Sosnowski said. “They have not really impacted prices for two reasons, especially over the last six months: They are not a significant portion of the market, and the price point for these properties is much lower (than what a typical buyer is looking for).”

Still, he noted that in other parts of Maine, foreclosures remain far more prevalent. Statewide, 411 of the 2,699 home sales that occurred over the past six months involved a foreclosure, he said, about 15 percent of all sales.

Another key indicator that CoreLogic tracks is the share of mortgage holders who are at least 90 days delinquent on their payments, referred to in the loan industry as “serious delinquency.” In January, 4.7 percent of all Maine home mortgages were in serious delinquency, down from 5.5 percent a year earlier. The national average for serious delinquency in January was 3.2 percent, down from 4 percent a year earlier.

The Bureau of Financial Institutions report notes that serious delinquency is far lower among mortgages issued by Maine-chartered banks and credit unions, which the bureau regulates. The serious delinquency rate was just 1.6 percent among such mortgages in December, down from 1.9 percent a year earlier. Only about 10 percent of all Maine mortgages are issued by state-chartered banks, Lund said.

John Barr, the bureau’s deputy superintendent, said Maine-chartered institutions never issued “predatory loans” that set borrowers up for failure with interest-rate spikes, balloon payments and other troublesome features. Those are the loan types that caused so many borrowers from large, national banks to lose their homes.

“(The large, out-of-state banks) were after the deal, and not out to help the borrower in many cases, unfortunately,” Barr said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.