The last time I wrote about Diane Bowie Zaitlin, her work came in the form of exquisitely brutalized encaustic painting. “Crimson,” a painting in her 2015 show at the Maine Jewish Museum, for example, appeared to me as “flayed flesh, a wound.” Zaitlin’s new work at June Fitzpatrick Gallery takes off from this point, but instead of continuing its metaphorical ravages on the human body, Zaitlin takes a black and white path into the jagged edges between drawing and painting.

Zaitlin calls this new body of work “drawing.” Considering the surfaces of the works are covered with paint, they could be seen either way. But the artist insists, and it seems she does so for the right reasons. Many of her works begin as horizontal surfaces – think paper on a table, rather than a canvas on an easel – covered with a layer of creamy white acrylic paint. It’s an intriguing switch from Zaitlin’s general paint of choice, encaustic, an ancient wax medium that can be reheated and reworked. Acrylic dries quickly, relentlessly and permanently. Zaitlin works the wet surface with drawings tools like graphite (pencil), but from the moment the acrylic is applied, the clock starts ticking.

Zaitlin’s encaustics and acrylics convey an extremely rapid process, since there would be merely minutes for the artist to work the medium while it is still pliable. The audience experience of encaustic is a fine craft mode in which the physical details of the object and the technique play a major role. But, in her acrylic works, we face objects that are literally, and quite apparently, raced to completion.

The common comparison would be “gesture drawings” done from a model in very short poses – 15 seconds, a minute and so on. But Zaitlin also includes several works from her more typical painterly mode that reveal extensive layering, detailing and time in the studio. One of these pieces, “Vestige,” is a vertical abstract painting on a panel. It is largely white, although many layers of color and surface marks are revealed. It’s an elegant piece, but when compared to the sparest and most quickly slashed out works, like the “Rhythmic Stand” series, the softly colored under-structure of “Vestige” feels rather decorative and the richly textured surfaces only reinforce its status as a luscious object. These qualities are hardly flaws, but they feel very far away from the sharp-edged accomplishment of the new work which they throw into high relief.

Zaitlin’s three “Rhythmic Stand” works appear to have been executed simply in white acrylic over a wide and loose horizontal black band that crawls across the middle of the vertical sheets of Bristol paper. It appears that after the white was applied uniformly over the paper, Zaitlin rapidly worked the surfaces with violently abrupt vertical slashes of graphite and possibly a palette knife. These works are not even remotely representational. They appear to have been executed in seconds, so quickly, in fact, that the artist could hardly have followed a plan or corrected a course if she had one.

Despite being monochromes, their wildly expressive gestures are clearly opposed to the coolly conceived, brainy intentionality of minimalist art. They succeed by hitting a nerve right between the muscle of painting and the bone of drawing.

Drawing appears as a violent interruption of painting: The pencil pushes the paint out of the way. Paint is reversed from being a color on a white background to the white of the ground, playing on painters’ proclivity to cover every inch of a canvas with color. And then it is only through the intervention of the trough-creating graphite that the paint is articulated as paint.

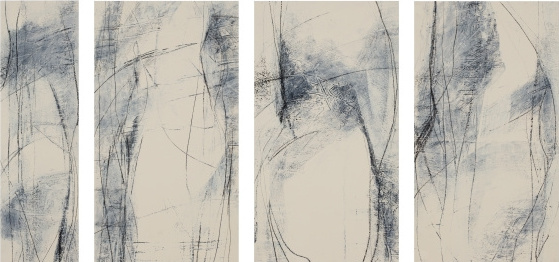

These works are spare, but the energetic insistence of this and similar suites exudes a sense of what the French call “élan vital” – the vital force of life. It is not surprising, then, that a similarly scaled vertical suite of four such works, “Gestation,” looks to the shape of a woman’s pregnant belly. While quite beautiful, they are too easily read as gesture drawings and so lose the high-wire philosophical drama of works like the “Rhythmic Stand” series.

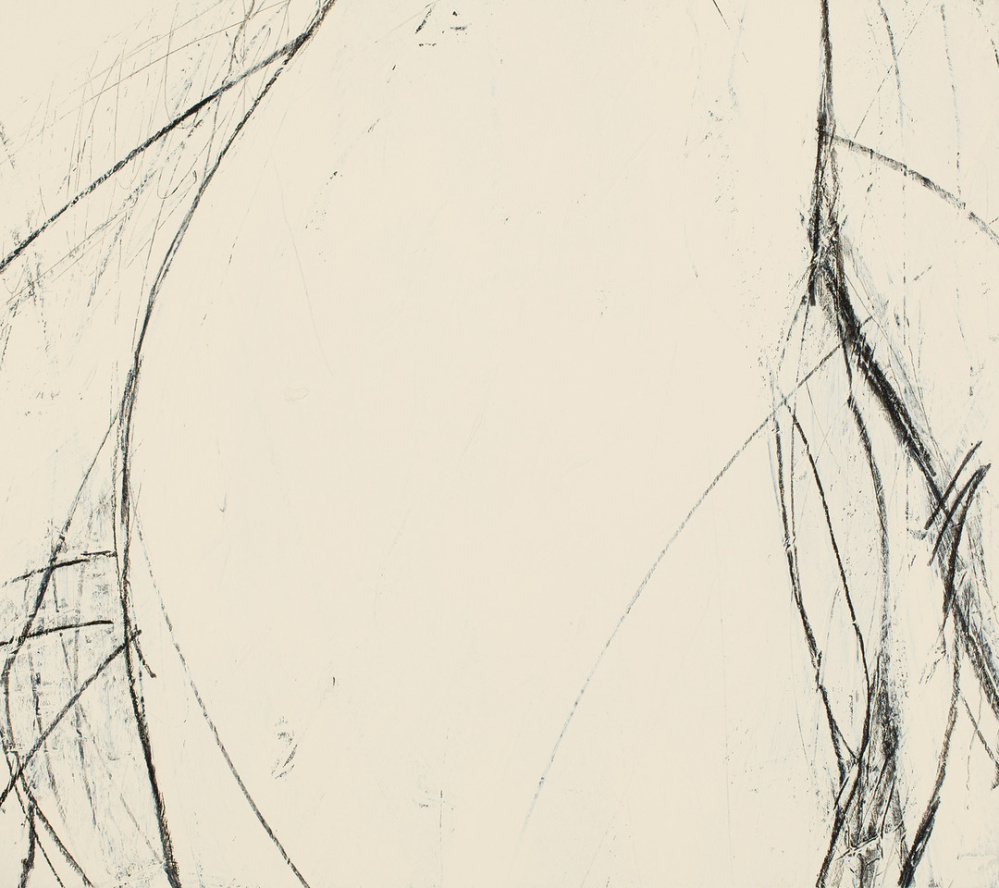

“Await” is a work that could join the representational “Gestation” pieces but, on its own, strikes a successful formalist sleight of hand that reaches out to the acrylic billows of Morris Louis, Andrew Wyeth’s ghostly white curtains, Willem de Kooning’s early curving forms only executed in his black and white “Attic Series” style and, more than anything else, Jackson Pollock if only he had survived that wreck.

There is a great deal more in “Drawings”: several elegant pairs of vertical Kitakata strips with wax and oil stick, colorful monoprint grids with hand shapes, mixed media panels on which vertical strips of paintings appear to have been quickly razored and then assembled with encaustic, and a tiny comprehensive suite of four encaustic squares. But it is Zaitlin’s most abstract and slashing graphite-on-wet-acrylic works that have taken her to another place.

This time, drawing appears as painting’s wound – where Zaitlin has slashed it right through the gestalt.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.