George Neptune, a Passamaquoddy basketmaker, calls the images heartbreaking.

Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, director of the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, says they’re challenging.

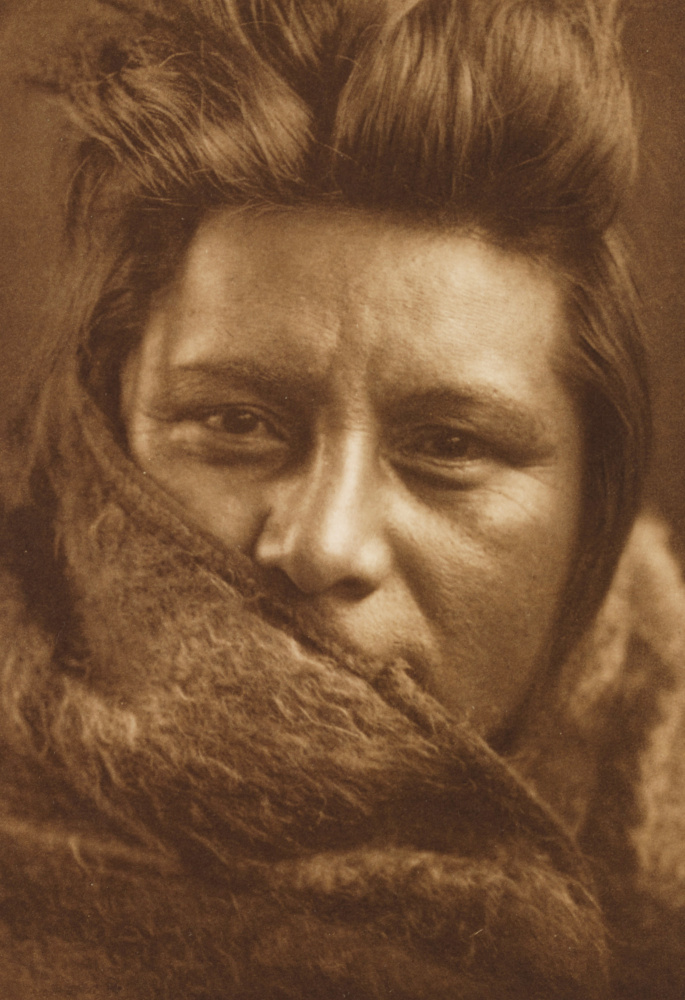

And canoe maker David Moses Bridges can’t get past the sadness. “If you look into their faces you can see the sadness,” Bridges says in a recorded gallery audio tour. “You can see the pain and the suffering that they had to endure, that they are enduring at the time this photograph was taken.”

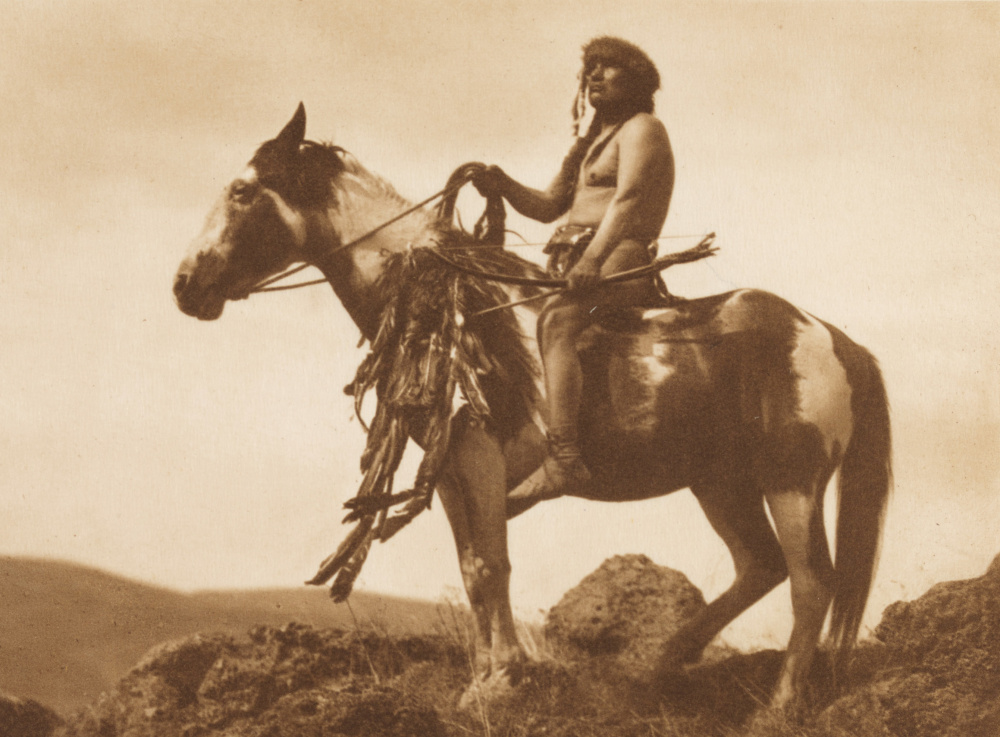

Bridges makes that observation while describing his reaction to the cream-colored photograph “Cayuse Mother and Child,” taken by Edward Curtis in 1910. It is one of two dozen images that make up the third-floor exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art, “Edward Curtis: Selections from the North American Indian,” on view through May 29.

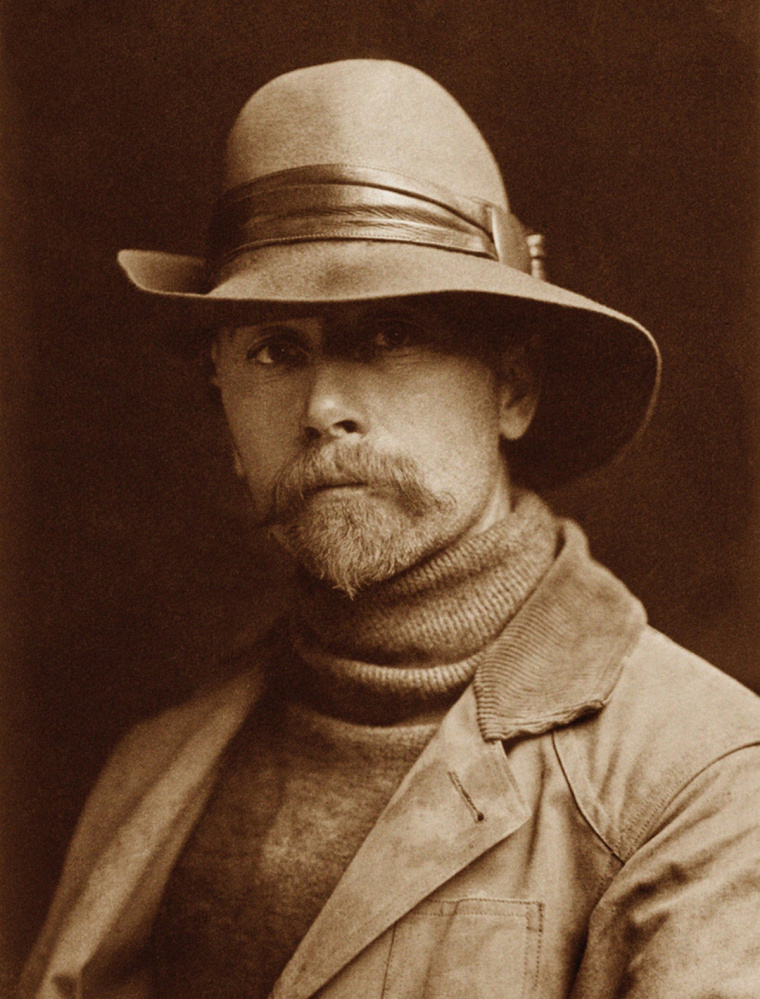

A Midwesterner, Curtis spent the better part of three decades photographing Indians in the American West and eventually published more than 2,200 photographs in 20 volumes under the title “The North American Indian.” The Portland museum owns 80 Curtis prints.

The photos are controversial, because Curtis was unfaithful to his subjects. He posed them out of context, removed modern references and created stereotypes.

Mollie Armstrong, exhibitions coordinator at the museum, said the Curtis show evolved from the curatorial staff’s deep dive into the museum’s permanent collection in preparation of its “Masterworks on Paper” exhibition now on view on the first floor. The Curtis photos, which came to the museum as a gift in 1974, have been shown a few times over the years, but now seemed like a particularly good time to revisit the collection, with context. Issues related to native culture and politics are popular, and more attention is being paid to native arts and crafts generally, she said.

For the first time, the museum included Wabanaki basketmakers in its biennial in 2015. The Curtis exhibition is coincidental to the inclusion of basketmakers in the biennial, but both reflect the museum’s sensitivity to the subject and its desire to tell a more complete story, Armstrong said. “This is the kind of story you have to tell,” she said.

The photographs represent an immense effort on the part of Curtis, who endured a failed marriage and personal bankruptcy in pursuit of the Indian project. He visited more than 80 tribes, recording histories, customs, artifacts and clothing of hundreds of Indians. It could have been monumental, but Curtis romanticized his subjects, and instead of creating a photographic record that was historically accurate, he blurred facts and perpetuated myths still associated with American Indians today.

The sadness detected by Bridges underlies a truth that was present in native culture. At the time Curtis took these photos, Indians had only recently been removed from their native lands and forced to live on government reservations. Their language and traditional ways were discouraged and sometimes forbidden, their culture something to be forgotten and not celebrated.

Bridges notes in his audio tour, there were about 250 Wabanaki people in Maine on the federal census in 1900. “And the future certainly did not look bright, at that time,” he says. “They were hanging on for dear life just to exist as Wabanaki people. And maybe just to exist, period. … That was a tough time to be indigenous.”

Curtis worked out West, and did not photograph the Wabanaki. But the story the photos tell are universal truths to native people. The museum is showing these photos in that context, promoting their beauty and the care that Curtis took in composing them – as well as his dedication to his subject – while including the voices of contemporary Maine artists like Bridges and Neptune, who are also Wabanaki. Neptune will give a gallery talk at noon May 6 and participate in a panel discussion that afternoon with Darren J. Ranco, chair of Native American Programs at the University of Maine, and others. Catlin-Legutko will moderate.

“What’s challenging is that when Curtis did this photography, he glossed over the parts of the American Indian experience that were devastating,” Catlin-Legutko said. “He showed this noble savage, and that identity carried through several generations. It’s a historic record, but you have to take it at surface value.”

Neptune, whose baskets were included in the museum’s 2015 biennial, resents the idea perpetuated in these photographs that Indians are of the past. “The entire photo series reinforces the stereotype of the disappearing or vanishing Indian,” he said. “It’s very damaging long term. The more you think of people as something in the past, it makes it easier to dehumanize those people now.”

The contemporary discussion about Indian mascots for sports teams is “closely related” to issues raised by the Curtis photos, he said. The mascots often embody the warchief-on-horseback images that Curtis staged, and Indian voices are disrespected in the discussion, he said.

Neptune doesn’t blame Curtis directly for the issues of stereotype and cultural exploitation that exist today. Curtis was part of a larger cultural phenomenon associated with the West. His photos were a byproduct of American expansion and its doctrine of Manifest Destiny, which justified the removal of Indians from their lands as an Anglo right and a consequence of progress and economic prosperity.

Neptune, an educator at the Abbe, credits the Portland Museum of Art for including Indian voices in the conversation and for providing context. “Normally people do not think of getting the Native American perspective,” he said.

On May 1, the Abbe Museum will open a large-scale permanent exhibition, “People of the First Light,” that tells a 12,000-year narrative of the Wabanaki Nations, a confederacy among the Abenaki, Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot. Part of that story is about resilience and contemporary meaning and relevance, Neptune said.

While not part of the Abbe exhibition, the Curtis photos are related because they represent colonization from the Anglo perspective. The Abbe exhibition will tell the Wabanaki story from a non-colonial perspective. The exhibition in Bar Harbor and the decision of Portland curators to include Indian voices in the Curtis show “are amazing examples of what de-colonization can look like when talking abut native culture and history,” Neptune said.

Nearly all the photos in the exhibition came to the museum from Julius and Frances Elowitch of Portland. Their son is Rob Elowitch, who operates Barridoff Galleries in Portland.

“They knew nothing of photography but were fascinated by the Curtis photographs,” Elowitch said of his late parents. “They had become available to me through a friend at the time, and I recommended they buy them and one day, perhaps, give them to the museum, which is what they did.”

Elowitch was surprised that the Portland exhibition is composed nearly entirely of the Elowitch gift. The lone exception is “The Fisherman, Wisham,” taken in 1904. That came as a gift in 1998 as part of the collection of Judy Ellis Glickman.

Elowitch calls the Glickman photo an “extraordinary addition” to his parents’ collection. In it, Curtis shows an Indian fisherman perched on a rock, peering over the side into churning water. His arms are outstretched, and he’s holding what appears to be a long spear in his hunt for fish. The impossibility of his task seems immense, and Curtis almost certainly posed his subject, who is barefoot and covered only at the waist by a small cloth.

Neptune flinches at the photo. It fits what Curtis perceived an Indian should look like, he said.

Neptune visits schools often as an educator and an artist. Now and again, a child asks if he rode to school on a horse, he said. And that same child never understands why he’s wearing sneakers instead of moccasins.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.