Inmates never get the holiday cards sent by family members to the Cumberland County Jail in Portland. Instead, jail staff members give them black-and-white photocopies of the originals.

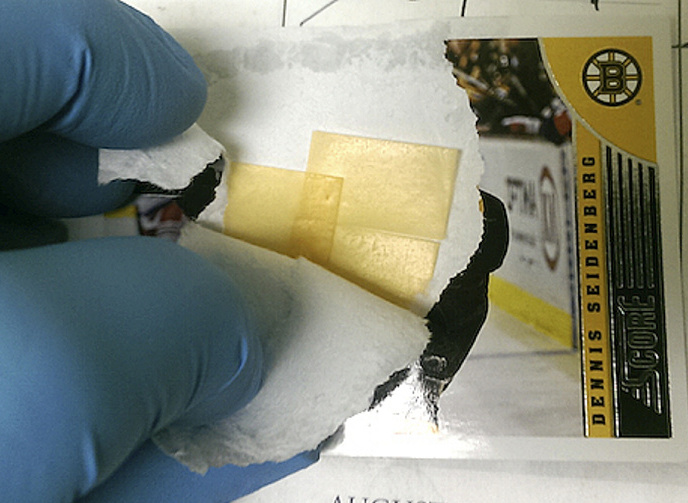

That’s because manufactured greeting cards are made with multiple sheets of paper – perfect for allowing someone to unglue the sheets, line them with contraband drug strips and glue them back together for smuggling into the jail.

Cumberland County Sheriff Kevin Joyce used that as one example of the ever-increasing number of steps the jail staff is taking to keep drugs from being smuggled into the state’s busiest jail.

But even those efforts weren’t enough to save 24-year-old Nikco Walton, a jail inmate who investigators believe died of a fatal dose of smuggled drugs on April 11 while in a cell shared with his sleeping cellmate.

The state Office of Chief Medical Examiner has not issued a final determination of the cause and manner of Walton’s death, and Joyce said it’s too early to speculate. But Walton’s attorneys say jail officials theorize that Walton swallowed a drug-filled balloon before his arrest April 5, and died after it failed to pass through his system and ruptured.

The attorneys, Amy Fairfield and Cory McKenna, are skeptical about that theory. They said it’s much more plausible that Walton died from drugs smuggled in by someone else and given to him in jail.

Regardless of whether Walton may have smuggled in the fatal dose himself or got it from someone else behind bars, corrections officials and the lawyers all agree it’s almost inevitable that smuggled drugs get into Maine’s jails and prisons and into corrections institutes across the nation.

Drug or alcohol intoxication accounts for nearly 7 percent of inmate deaths in local jails, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics for the years of 2000 to 2013.

In 2013, the most recent year for which complete data are available, 967 inmates died in the nation’s jails. Seventy of the deaths were from drug or alcohol intoxication, the report says.

The report tracks mortality numbers separately for jails, which hold inmates serving short-term sentences or being held on bail, and prisons, which house inmates serving longer terms, including life sentences.

“I’ve been pretty candid that these guys have been working their hearts out trying to keep drugs out,” Joyce said of the correctional officers at the jail. “You are only as good as what you can find and what you can legally, constitutionally do.”

Until about two months before Walton’s death, staff members at the Portland jail had used a full-body scanning machine owned by the Maine Department of Corrections to search all inmates about to be admitted to the jail for drugs hidden inside their bodies, Joyce said.

That process was labor-intensive because the sheriff’s office had to drive all inmates to the Maine Correctional Center in Windham, the nearest prison with a body scanner. But it was highly effective, Joyce said.

When the state’s machine in Windham began malfunctioning, jail staff had to abandon the practice. Joyce is now hoping to purchase a dedicated body scanner for the jail, but the cost of between $225,000 and $250,000 may be prohibitive.

TRYING TO STAY ONE STEP AHEAD

With no help from a body scanner, the jail staff is now searching inmates as much as legally allowed, prohibiting inmate contact with visitors, keeping a strict mail policy, and conducting frequent urine screens and cell searches, Joyce said.

“We’re always staying one step ahead of the inmates,” he said.

Jody Breton, the deputy commissioner and spokeswoman for the Department of Corrections, initially declined to comment on any questions for this story, including some about the Windham body scanner. She then said Thursday that she would try to answer questions by email, but she failed to respond by the end of the day Friday.

Joyce said that after Walton’s death, corrections officers had all inmates in his jail pod, C1, undergo screens to see if they had drugs in their systems. But those inmates all tested negative.

The Portland jail holds up to 500 people at a time, with a constant flow of inmates coming in or being released. About 65 percent of the inmates are held temporarily while awaiting court appearances after arrest, or are being held on bail pending trial. They typically face charges ranging from driving with a suspended license to murder. The other 35 percent are serving short sentences.

A CHALLENGE AT YORK JAIL, TOO

Drug smuggling is an equally vexing problem for the York County Jail in Alfred, which serves the second-most-populated region in the state.

“It’s a real challenge,” said York County Sheriff William King Jr.

King said that within the past year, four inmates – three women and one man – overdosed at the jail but were saved by jail staff. He credited jail nurses and intake staff with acting quickly and recognizing the signs of inmates who arrived under the influence of drugs.

King said addicts wanted on arrest warrants who are about to surrender themselves at the jail will sometimes try to smuggle drugs inside their bodies to avoid suffering from withdrawal while they are locked up.

Another difficulty is that even when narcotics officers alert the jail staff that a newly arrested drug suspect may have swallowed packaged drugs, it is difficult to then recover those drugs.

King said that in one instance, an unlucky corrections officer at the Alfred jail was assigned to stay with an inmate each time the inmate used the toilet to try to recover the swallowed drugs when they passed through his system. But the inmate stymied the guard by flushing the toilet against orders.

In another instance, an inmate carved a hole in the bathroom wall to hide drugs he had defecated and then sealed the hole with toothpaste in a failed attempt to avoid detection.

“It really illuminates the power of addiction,” King said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.