The numbers are startling: Overdose deaths in Maine increased 31 percent last year, killing 272 people. Nationally, there was a sixfold increase in deadly heroin overdoses between 2001 and 2014, and overdose deaths more than tripled in the same time period.

More startling than the numbers are the human losses. The people who are killed by overdose and the people who continue to struggle with addiction aren’t just data points on a trend line. They are children, parents and lovers. To understand addiction and find effective solutions, we have to understand the nature of addiction on a personal level.

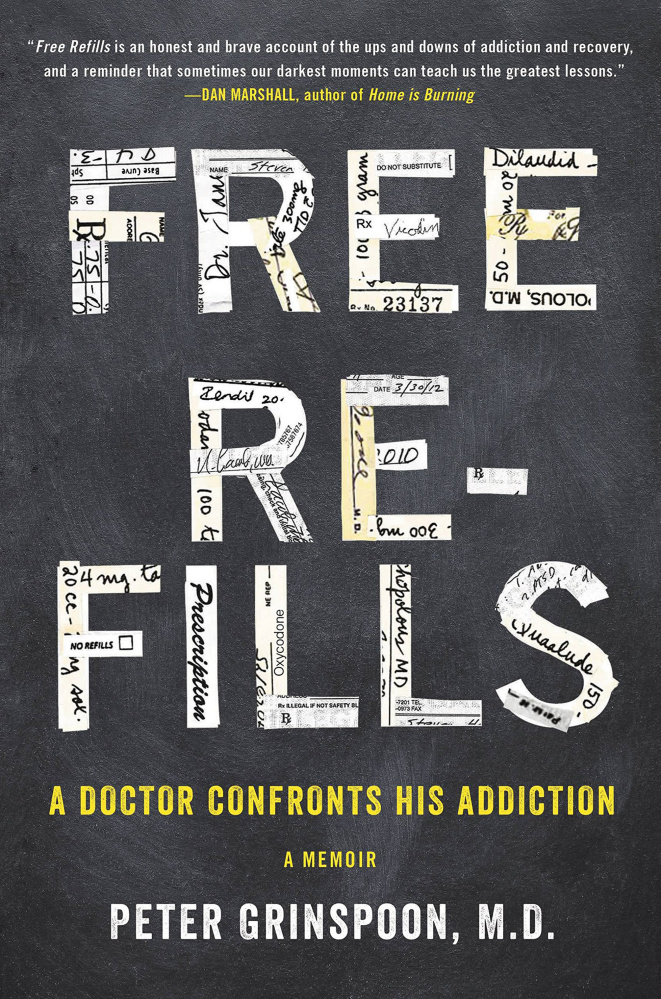

Dr. Peter Grinspoon describes his personal experience as an addicted physician in “Free Refills: A Doctor Confronts His Addiction,” a fast-paced account of his descent into drug use and his slow and uneven path to recovery, which included several relapses.

Grinspoon, a primary care physician in the Boston area, provides an eye-opening view into the lengths he went to to obtain drugs. He would write fake prescriptions, pilfer drugs from the supply cabinet at his medical office, scarf up drug samples from pharmaceutical companies, and steal pills from the medicine cabinets of his dinner hosts. Sometimes he would even go back to his office at night and inhale “hits off the tank of nitrous oxide in the neighboring doctor’s office.”

Grinspoon didn’t confront his addiction voluntarily; he was compelled to do so after being arrested on three felony charges for fraudulently obtaining narcotics. Describing his sense of horror when law enforcement agents appeared in his medical office, he said his “universe started collapsing, even imploding, like a balloon stuck with a pin.” Instead of responding by calling his wife, his lawyer or his therapist, Dr. Grinspoon hurried to his drug stash and took eight oxycodone pills.

With criminal charges pending, Grinspoon tried to preserve his medical license by meeting voluntarily with the Society to Help Physicians, a program for physicians confronting substance abuse. But he was in a state of denial and would admit only to smoking pot and taking medicine for migraines and insomnia. Immediately after the meeting he congratulated himself on how “easy” it was “to fool” the addiction doctor. Nevertheless, he knew his “addiction was fighting for its life” and he quickly headed to his supply of Percocets for chemical reinforcement.

Initially, Grinspoon was able to keep his medical license by agreeing to random drug testing. But he used drugs and failed a drug test, setting off a “chain reaction of ever more painful and long-lasting consequences.” The first of these was that he “voluntarily” surrendered his medical license. Shortly after that, he found himself locked out of his medical office (“I’m sorry, Dr. Grinspoon, the locks have been changed and I’ve been instructed not to let you in.”)

Looking back at this incident, Grinspoon now agrees with the lock-out decision because, he writes, “Addicts, myself included, are scary and they steal. They are nothing but trouble.”

Soon after, his wife threw him out of their house and Dr. Grinspoon went to live with his parents. He describes the “cosmic irony” of having to move into his parents’ house because of addiction problems: His father is a prominent psychiatrist who specializes in substance abuse. He realized that he was facing a serious challenge and needed to “wake up and start paying attention.”

After beginning a 90-day residential treatment program in North Carolina, Grinspoon at first vehemently rejected the idea that he had anything in common with other people addicted to drugs. During his stay, he came to see that, even though he was from “the heights of Harvard Medical” and other residents were Kentucky miners “from the darkest depths of the coal pits, we were brought to the same place by the same drug.”

Grinspoon traces his addiction to three factors, starting with access to an abundance of illicitly obtained Vicodin during medical school. He writes that “thirty minutes after swallowing my first Vicodin, I felt a rapid rise of bliss in my heart, swelling to a state of happiness I had never known.” His addiction counselor would later say that this first experience with Vicodin “changed [Grinspoon’s] brain forever.”

The second factor, Grinspoon notes, was the stress early in his medical career from long shifts, sleep deprivation, emotionally challenging patient care and trouble in his marriage. He found pills to be “a quick fix” for life’s challenges.

Thirdly, he notes that, as a physician before the prescription drug crisis was recognized, he had almost unfettered access to drugs at the hospital, in other doctors’ offices and in clinics where he practiced. When he got his medical license and a prescription pad, it was like “giving a book of matches to a pyromaniac.”

Access to drugs was nothing new for Grinspoon. Growing up “we always had abundant weed” from his “dad’s reefer closet,” but he remains skeptical about what impact his early marijuana use had on his later addiction to opiates.

After completing the 90-day inpatient program in North Carolina, Grinspoon was clean for a while but then started taking a “few pills here and there.” He initially avoided detection on random drug testing by analyzing, with scientific rigor, the probability of being tested on a given day and mastering the steps he could take to get the drugs out of his system faster, without appearing that that he was trying to do so.

He relapsed again during a family trip, but this time he reported the slip to his probation officer, who – in what turns out to be a wise use of her discretion – did not report him to the judge.

By this time “the pain-to-pleasure ratio” of continued drug use was “worsening by the hour.” He felt “an almost physical sensation of a new resolve forming within me.”

Eventually Grinspoon got his license back and returned to the practice of internal medicine where, as is probably common in medicine today, some of his patients are addicted to opiates. Unlike the times years before when he thought he was so different from street addicts, he now reflected that “our brain disease was identical.”

Throughout the book, Grinspoon’s sense of humor and ability to see irony and absurdity in his circumstances is constant. Recognizing the difficult and at times humiliating nature of his journey, Grinspoon writes, “You can laugh or you can cry.” For the most part, Grinspoon chose to laugh.

It was difficult for Grinspoon to get to a place of stable recovery, but his personal circumstances increased his chances of success. He had money for a 90-day residential treatment program and a comfortable home in tony Brookline, Massachusetts. He was also motivated by the desires to be with his two children and to return to the practice of medicine. He even had a fallback home he could go to when his wife asked him to move out. Despite all these advantages, he relapsed repeatedly.

Imagine how much more difficult recovery must be for addicts who don’t have financial stability, a support system and access to good treatment.

Even for Grinspoon, who has been drug-free for almost a decade, recovery is an ongoing project. “Over time,” he writes toward the end of the book, “these pills sing to me less, but if I listen carefully they still quietly beckon.”

Dave Canarie is a Portland attorney and adjunct faculty member at the University of Southern Maine and Saint Joseph’s College.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.