Joe Gould was a bohemian charmer whose Harvard connections provided the springboard to a literary life. His friends included e.e. cummings and John Dos Passos, William Saroyan and Ezra Pound. Gould dubbed himself “the most important historian of the twentieth century.” He devoted his waking hours to a seemingly endless, groundbreaking work, “The Oral History of Our Time,” in which he detailed his conversations with, and observations about, everyday people in New York.

That’s one view of the man. Another is that Gould was a psychopath who bounced between magazine jobs and mental hospitals; a beggar, a stalker and a drunk.

The question isn’t which version of Joe Gould is more accurate; it’s how we ever came to know about this strange, sad man, and the myth-making that surrounded him.

And what ever happened to that self-proclaimed brilliant tome that Gould was writing, anyway?

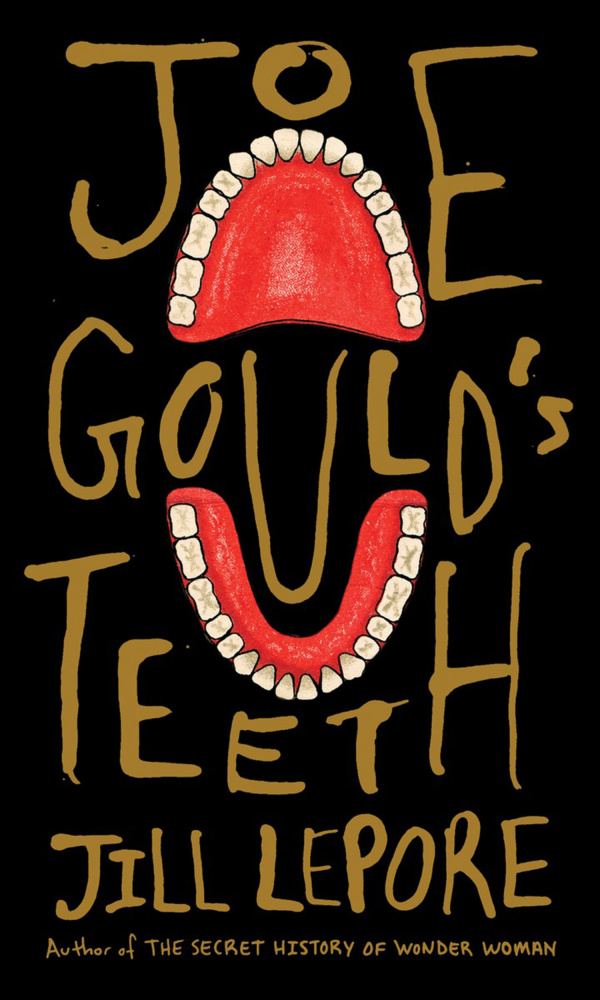

Enter acclaimed historian and bestselling author Jill Lepore, whose fascinating book, “Joe Gould’s Teeth,” is a tragicomic tale of a madman at the intersection of history, fame and fiction. Lepore began with a simple enough premise: Teaching a course on biography at Harvard, she was compiling a syllabus on how to research and chronicle people’s lives. She sought material that would illuminate the difficulty of truly knowing any person. Among her reading selections were two well-known profiles of Gould, written by Joseph Mitchell, that ran in The New Yorker. The first, “Professor Sea Gull,” in 1942, launched Gould into the public eye with its praise for the pioneering oral history he was writing. The second, “Joe Gould’s Secret,” in 1964, was a reassessment of the earlier piece, questioning the oral history’s very existence.

Lepore’s book is not only a work of scholarship, but a layered gem of storytelling. It’s a puzzle, mystery and archaeological dig rolled into one. Lepore details her travels to libraries and archives, unearthing boxes and files of material relating to Gould. It became clear that Joseph Mitchell knew he’d been duped early in the game. In the course of his research, he had seen only a few pages of Gould’s so-called history. But Mitchell also knew something about invention, having “composed” a novel in his head that never made it to the page. He recognized himself in Gould.

The book proceeds to entertain with numerous subplots and intrigues, assorted exchanges among luminaries, and more than one unreliable narrator. Joe Gould was a liar and fabulist by definition; he was clinically delusional. And it turns out that Joseph Mitchell had a sketchy relation to the truth, as well. In certain New Yorker pieces, he fabricated scenes and quotes, even a profile of a man who never existed.

“Joe Gould’s Teeth” depicts a charismatic, deranged man who lost everything he ever touched – his eyeglasses, his false teeth, the manuscripts he was writing – and ultimately succumbed to mental illness. And it renders Joseph Mitchell a collaborator of sorts, with his own quirks and obsessions.

“A century on, Gould looks bleaker, his mental illness looks more serious,” Lepore writes. “Gould’s friends saw a man suffering for art; I saw a man tormented by rage. … Mitchell met one man; I met another.”

This is a book about how we record history and what constitutes the historical record. It’s also about the line between fact and fiction. At bottom, the book highlights the limitations of observing and reporting on other people, and the inevitability of bias.

It’s easy to imagine Lepore’s vivid, unsettling book listed on a syllabus of some future course on biography. As she trains her lens on Joe Gould, and widens out to his broader circle of prominent friends and abettors, she offers a cautionary tale for us all. The world is inextricably our mirror; we see ourselves everywhere. Our blind spots come with the territory. Which is how the story of Joe Gould ever saw the light of day.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.