BAR HARBOR — If nothing else, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko wants people who visit the Abbe Museum to leave with one piece of knowledge firmly planted forever in their brain: Native people still live in Maine.

“It’s amazing how many of our visitors don’t realize that,” the museum director said. “They’re always surprised.”

That may reflect, in part, how the museum told its story in the past. The Abbe sometimes told the Native story from the perspective of history, using domestic artifacts and items discovered in archaeology digs to inform visitors about how Indians lived and what their lives were like.

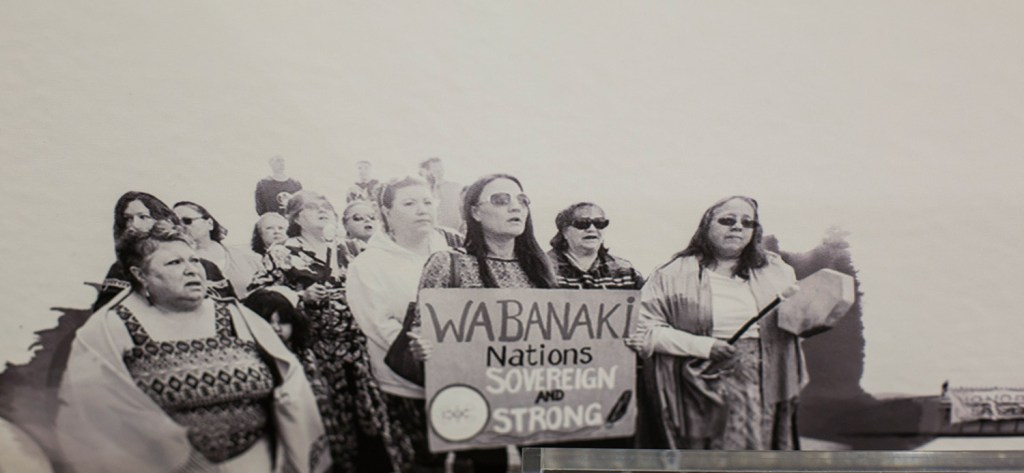

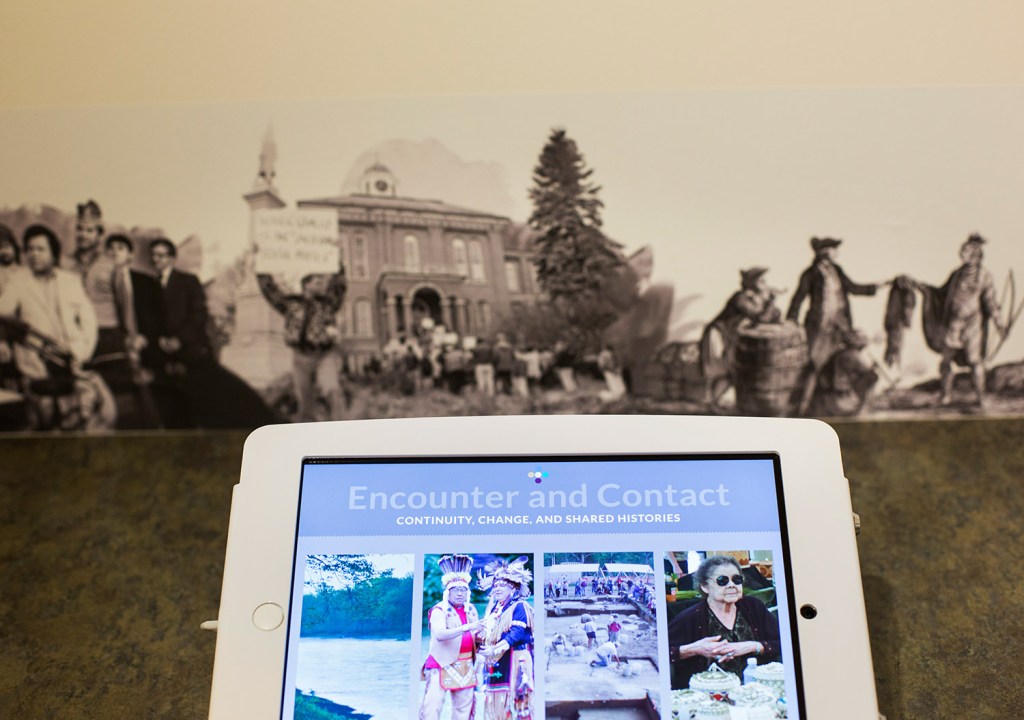

That storytelling method has changed. The only museum in Maine dedicated to Wabanaki history and culture has opened a long-term exhibition, “People of the First Light,” that tells a 12,000-year narrative of the Native culture in Maine, including the present.

It could just as easily be titled, “We’re Still Here.” The museum, which includes Native Americans on its administrative and curatorial teams, worked with tribal representatives across Indian country in Maine to tell a story from the Native perspective. In the museum world, that process is known as “decolonization,” and the Abbe is earning praise for its aggressive implementation of the practice. In the past, it might have told a similar story, but without the direct perspective of the Native Americans either in presentation or conception, or omitting key historical moments or events that have caused trauma and turmoil.

“It means not following the standard narrative of how the country was settled and bringing in broader perspectives and multiple points of view,” said Harold Closter, director of Smithsonian Affiliations, which encourages partnerships among museums and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. “It means recognizing there were people here and those people are still here and they are part of the fabric of our history and our national culture.”

The Abbe, the only Smithsonian affiliate in Maine, has been practicing decolonization for a few years, but formally adopted the principle as part of a new strategic plan in 2015. “People of the First Light” is the first exhibition where it’s fully expressed. Most voices in the exhibition are Indian voices, and many are the voices of Indians living in Maine today. The museum worked with nearly 30 Wabanaki curators, consultants and artists to create the exhibition, curator Julia Gray said.

The move toward decolonization is not new. Some museums have been practicing it for two or three decades. We’ve seen it recently in Maine with the exhibition of Edward Curtis photographs at the Portland Museum of Art through May 29. Catlin-Legutko moderated a discussion at the PMA about the photographs, to put them in context with when they were taken and how they’ve been interpreted over time and the hurtful stereotypes they have helped perpetuate.

The new Abbe exhibition includes objects and artifacts from Indian life we’re conditioned to expect to see: Birch canoes, woven baskets made from wood, domestic items unearthed in archaeological digs and regalia from ceremonial occasions. There’s a display about language, including audio of Native speakers. Another shows the Wabanaki homeland before “(e)xplorers, colonizers, and non-Native people and governments” imposed boundaries and their own names.

The exhibition also includes information that may be less expected. One kiosk includes information about the legal fights for water rights that Indians have waged in Maine. Another has stories from the state Truth & Reconciliation Commission, which investigated why so many Wabanaki children have been removed from their homes by the state.

Another kiosk is dedicated to headlines from articles about Native issues that are regularly updated. The most recent ones were from an Indian mascot controversy in the Maine town of Skowhegan.

“These are hot issues and news headlines that are important to Native people today,” Catlin-Legutko said. “They are exactly the issues we should be exploring.”

Among the consultants was Donna Sanipass of Presque Isle, whose parents, Mary and Donald Sanipass, were well-known Indian basketmakers in northern Maine. Donald Sanipass died in 2006, and Mary is still making baskets at 80.

The museum wanted to show some of their baskets. A basketmaker herself, Donna Sanipass agreed to work with the Abbe because she is proud of her heritage and dismayed how little people know about Indians from Maine. “It is very important that people know who we really are. We are not from the West,” Sanipass said. “Our traditions are a bit different form people out in the West. When people ask about me — they don’t even ask about me. They just say, ‘My grandmother was a Cherokee.’ And I am supposed to relate to that? It’s important that people know who we are, our culture. It’s not what they see on TV. It’s not what they read in the history books.”

Gina Brooks, a Maliseet Indian from Wabanaki territory in New Brunswick, Canada, has shown her art at the Abbe on many occasions and will serve as an artist-in-residence this summer. She helped the Abbe illustrate a section of the exhibition that deals with traditional storytelling. Her art includes basketry, carving and printmaking.

She credited the museum staff — Natives and non-Natives alike — for taking on topics important to Native people, such as water rights and border issues, and exploring them from the perspective of art and culture.

“The Abbe really wants people to understand our perspective,” she said. “They advocate on our behalf and have accepted the challenge to understand us better.”

The Wabanaki confederacy, also known as “People of the First Light” or “People of the Dawnland,” includes the four principal nations of Indians in Maine: the Micmac, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot.

Beth Harris Hess of Cape Elizabeth toured the exhibition last week. She noticed the new storytelling tone, and was impressed with what she described as “an authenticity” in the collection and how the culture was presented. “What impressed me most deeply about the Abbe was the way the entire collection has been designed and executed with full integration and involvement of Maine’s modern native peoples,” she said.

A little more than two years ago, the museum joined the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, a member organization based in New York and including about 200 museums and historic sites that connect the past to present to preserve stories so people can learn from history and the mistakes of their ancestors. The coalition promotes the telling of difficult stories, and among its principles is the idea that the need to remember often competes with the pressure to forget.

The Abbe joined the organization to learn how to answer the hurtful comments its staff encountered from visitors with information that leads to learning.

At the front desk, receptionists have been asked questions and overhead statements that have left them confused about how to respond:

“Those pictures don’t look like Indians, they look European. They probably aren’t real Indians anymore.”

“Are your Indians poor?”

“Bathrooms? I bet they didn’t have those in the tipis!”

“Can I touch an Indian?”

Sarah Pharaon, senior director of methodology and practice for the coalition, has been to the Abbe twice to work with the staff about communication and storytelling.

Too often, she said, museums and historic sites interpret history from the perspective of those who work there, and not from the perspective of those whose lives were, and in some cases still are, affected by what happened throughout that history. By empowering Native people from Maine to tell “their owns truths and their owns stories,” the Abbe is helping to reduce cultural hierarchy in Maine, Pharaon said.

In a short time, the Abbe has become a model for the International Coalition of Sits of Conscience, because it has embraced storytelling from the inside out. “Museums and historic sites have long legacies of fostering trauma and in some ways capitalizing and exploiting trauma,” she said. “The Abbe is one the museums leading the conversation on how we can critically examine the work we do and do in a better way.”

The Abbe opened in 1928 and is named for Dr. Robert Abbe, a New York physician and summer resident of Bar Harbor. He built a collection of early Native artifacts from the area, and established the museum at Sieur de Monts Spring in what is now Acadia National Park.

That original site is still open seasonally. The museum opened its main museum in downtown Bar Harbor in 2001. It draws about 30,000 visitors a year and operates with a budget of about $1 million.

Kathleen Mundell, who runs the Maine Arts Commission’s traditional arts program, called the Abbe staff “courageous” for exploring difficult issues and beginning difficult but important conversations.

“The museum world has shifted, and the Abbe is shifting with it. They are definitely telling their stories through the eyes of the people whose stories are represented,” said Mundell, who curated an exhibition at the museum in 2009. “It’s an important place for the state of Maine.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.