BRUSSELS — It was like Bernie Sanders versus Donald Trump in the heart of Europe, and the Bern won by a nose.

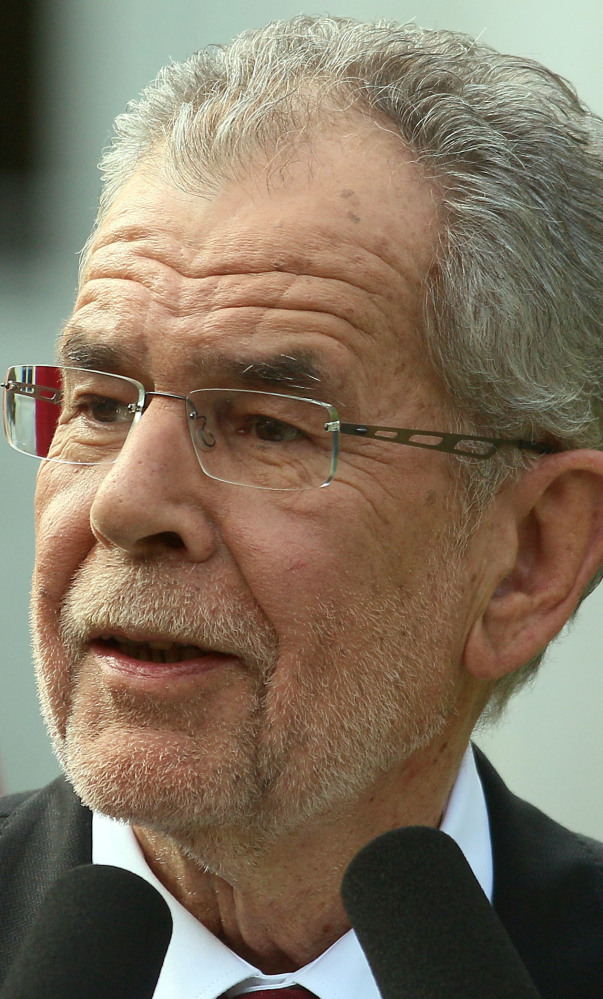

Left-wing economics professor Alexander Van der Bellen was elected Austria’s largely ceremonial president, holding off an anti-immigration nationalist who campaigned on a Trump-style “Austria First” platform.

But the nail-biter margin – 31,026 votes out of almost 4.5 million cast – signified polarization and gridlock, more of a defeat for the crisis-plagued European establishment than a victory of an alternative political program.

The tight vote “indicates not so much the strength of the extremes, but the weakness of the center,” said Timo Lochocki, a fellow at the German Marshall Fund in Berlin. “You win elections if you polarize and personalize and have a story to tell.”

Austria was fertile ground for the revolt because it has been governed by a cozy twosome of center-left and center-right parties for most of the post-World War II period.

With Austria’s mainstream parties blurring together and divvying up posts and patronage, the opposition was banished to the fringes. That ostracism ended in the first round on April 24 when candidates from the two traditional parties were eliminated.

“It’s a Europe-wide trend: The economic good times are over, and the search is on for new policies,” said Peter Hajek, a public-opinion analyst in Vienna. “And that’s where there’s a divergence of views.”

For some, the triumph of Van der Bellen, 72, over the Freedom Party’s Norbert Hofer showed the right can be stopped. Austria will get a Green Party-backed president to go along with a Social Democratic chancellor. For the Freedom Party, the near-miss was just a stepping stone to taking over the chancellorship, the real seat of power, in the next elections in 2018.

Austria rehearsed a right-wing rise once before, when the Freedom Party made it into the governing coalition in 2000 and then fizzled. Hofer, 45, would have become the first western European head of state in the modern era from the far right, a label he disputes.

Still, the electoral close call demonstrated that, in countries north of the Alps, the anti-immigrant variant of populism strikes a chord with voters even in an era of relative prosperity.

Austria has the third-lowest unemployment rate in the 19-nation euro zone, at 5.8 percent in March. A 4.2 percent rate in Germany, the lowest, hasn’t prevented the rise of a fledgling anti-euro, anti-immigration party there.

“Populist parties do not only flourish during recessions or in economically difficult times,” said Carsten Brzeski, chief economist at ING-Diba AG in Frankfurt. “The ingredients and underlying political trends of the Austrian presidential elections are likely to stay in the euro zone for a while.”

The Freedom Party’s platform is marked by blood-and-soil politics with an emphasis on (heterosexual) marriage, national identity and Christianity. It shares a focus on crime-fighting and skepticism of the European Union with other nationalist parties.

Austria’s balloting brought the era of voter wrath from places like Hungary, Poland, Greece and Spain to the EU’s core. Economic grievances mingle with hostility to the outside world and alienation from the EU’s coordinating bodies in Brussels.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.