MOUNT DESERT ISLAND — When Becky Friend and Bob Harding drove to the top of Cadillac Mountain to see the sunrise in June, the view of Maine’s coastal islands was perfect. But the traffic at Acadia National Park’s most popular scenic vista was unbearable.

“It was packed,” said Friend, who lives in Morgantown, West Virginia. “It’s our first time here. I was surprised.”

Cameron Seybolt of Minneapolis, Minnesota, said the same thing after driving to the Cadillac summit on his first visit to Acadia National Park. He said it was reminiscent of the bumper-to-bumper traffic at Yellowstone and Glacier national parks out West. He eventually found a parking space, but added: “I wouldn’t say it was no problem.”

Meanwhile, Irene and Duane Lefever of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, visited Acadia for the 11th time, and said they’ve learned not to visit in the summer.

“We come early in the season,” she said. “Now it’s crowded. But in July and August, it’s just too crowded.”

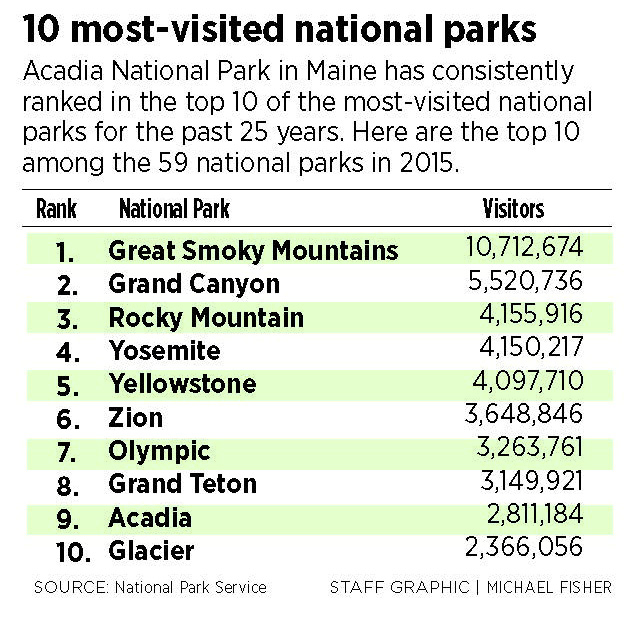

Acadia is one of the most visited of the 59 national parks, consistently outdrawing more famous destinations such as Alaska’s Denali National Park and the Florida Everglades. And the crowds here keep getting bigger. Last year 2.8 million people visited Acadia, about 300,000 more than the year before. Through May of this year – which is Acadia’s centennial – the number of visitors was up 27 percent over 2015. At that rate, Acadia is on track to see a record 3.5 million people pass through.

As it celebrates its 100th birthday Friday, Acadia National Park is at a crossroads. The 33,000-acre park with its dramatic seaside cliffs, rolling coastal mountains and rich forestland has offered a peaceful natural respite from busy life since July 8, 1916. Yet as an ever-increasing number of cars crowd the park from Memorial Day until Labor Day, park officials face a daunting challenge: how to help visitors enjoy the solace and peace of Acadia’s natural beauty free of crowds and car exhaust.

Acadia Superintendent Kevin Schneider, who arrived in January, said burgeoning crowds will be the biggest challenge for Acadia in its next century.

“Right now, there is not enough parking for a busy park day,” Schneider said. “The popular Island Explorer bus served half a million last year. We continue to wrestle with the key destinations with crowds, like Jordan Pond and Cadillac Mountain. We don’t want people stuck in traffic hunting endlessly for a place to park.”

This challenge is not unique to Acadia, of course. Tourists visiting national parks across the United States have the same complaints. But the ever-expanding crowds threaten to fundamentally alter the experience of visiting the beautiful park with the pink granite shoreline. Some would say they already have.

“From Yosemite to Yellowstone to Zion to the Arches to the Grand Tetons, they all are dealing with similar issues,” Schneider said. “Acadia’s centennial is the time to ask: How do we assure people will have a high-quality experience the next 100 years?”

INTERWOVEN WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES

In 1901, summer resident George Dorr spearheaded a conservation effort that resulted in the protection of 5,000 acres by the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations. The effort, undertaken to protect the mountainous and coastal region from development, ended up forming the core of Acadia, said author Ronald Epp, who wrote Dorr’s biography.

“Creating a national park was not their idea from the beginning,” Epp said.

On July 8, 1916, the trustees gave the land to the federal government, and President Woodrow Wilson announced the creation of Sieur de Monts National Monument. The name was changed to Acadia National Park in 1929, after the nickname given to the region by Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, who called the Atlantic Coast “Arcadia” after an area of Greece known for its spectacular beauty.

“Most of the parks out West came from federal land that was part of the Louisiana Purchase,” said Acadia spokesman John Kelly. “Acadia is an anomaly in that it was the first park that was not already federal land. It was land given to the federal government with the express purpose of making it a national (park).”

In the years that followed, other locals worked to preserve land around Acadia, most notably John D. Rockefeller Jr., who donated 10,000 acres to the park and funded the creation of the historic carriage roads.

All the while, the land parcels purchased and donated to the park were scattered alongside towns, and lacked the neat boundary lines that defined national parks out West.

“Most communities are shoulder to shoulder with Acadia,” Epp said. “There was nothing comparable west of the Mississippi in terms of a park laid out within this cocoon, with villages and towns surrounding it.”

Today Acadia sits beside small fishing villages on Mount Desert Island and the Schoodic Peninsula. The way Acadia is interwoven through these Down East communities makes it the only national park that is physically integrated into the surrounding towns and villages, said Jeffrey Olson, chief spokesman for the National Park Service in Washington, D.C.

“The communities wouldn’t be the same without the park,” Schneider added. “There is a very close interdependence between them.”

For the people who live on Mount Desert Island, the park is part of their neighborhoods. Backyards spill into the park, commutes to work cut through it, and free time is spent after work and school exploring Acadia’s trails and carriage roads.

“It’s like a dream to be able to do the work I do and then to have this as my backyard,” said Carol Bult, a scientist at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor who cycles through Acadia almost daily.

Those same locals could help solve Acadia’s traffic problems, Schneider said.

In January 2015, park officials began work on a transportation plan. This fall, the park will put out its recommendations for public review in the local communities. Normally, the park service’s “Environmental Impact Statements” are not vetted by local residents, Schneider said. But Acadia is different.

“Because of the fact Acadia is intertwined with the local communities and vice versa, we wanted to first get public input,” Schneider said. “We’ll ask them for alternatives we missed. We’re trying to come up with a range of options. We want the public’s feedback to help guide the park the next 10 to 20 years.”

SIGNIFICANT CHALLENGES AHEAD

As Bruce McNeil of Kalispell, Montana, stood with his 8-year-old son, Eddie, looking out across Schoodic’s vast granite patio and the ocean beyond, he reflected on how tranquil it was and how unlike other national parks he’s seen.

“It doesn’t seem crowded here,” said McNeil, who fled from the bustling park trails around Bar Harbor to enjoy the peace at Schoodic, a more remote part of Acadia. “At Glacier National Park, there is lots and lots of traffic. At Yellowstone and Grand Teton, there are always a stream of cars. I’m struck by how clean the air is here.”

Schneider said this is the goal at Acadia in the next century: to move the foot and automobile traffic in the park away from congested areas. The new Schoodic Woods Campground, with 94 campsites, is one step toward achieving that goal.

“There are a handful of destinations people go to but plenty of places in Acadia where you do not see a lot of people,” Schneider said. “This morning I was at Thompson Island picnic area, right where you come onto Mount Desert Island. It’s a wonderful picnic area that doesn’t get a ton of use. It’s right on the water. People need to know about those experiences.”

However, Schneider said, Acadia, because of its unusual design, has unique challenges.

Acadia’s 33,000 acres make it one of the smallest national parks. Glacier Bay in Alaska encompasses 3 million acres. Big Bend National Park in Texas is 800,000 acres. California’s Yosemite is 761,000.

And because of Maine’s colder climate, the busy summer tourist season is much shorter than at parks out West.

Finally, because Acadia is interwoven through surrounding communities, it’s difficult to capture gate fees from all visitors. Those range in price from $12 for a weekly individual pass to $50 for an annual vehicle pass.

“One of the challenges we have: People are unaware where the park begins and ends. There is no indication in many cases when you’re driving along the edge of it. This can become a challenge collecting fees,” Kelly said. “We know we miss about 30 percent of visitors who do not enter the gate at Sand Beach.”

This year Acadia is one of five national parks in a pilot program that allows visitors to buy park passes online. Park officials are also trying to do more to encourage visitors to use the mass transit system on the island, the free Island Explorer buses that run eight routes linking community centers in local villages to destinations in the park. More recommendations should come in the fall, Schneider said, and hopefully local residents will help come up with ideas.

“This is an exciting time for us,” Schneider said. “We want people to experience Acadia National Park. We want the park to be appealing to the next generation of park stewards. We want to make sure we provide a really high-quality experience. How do you do that when visitation is increasing at a fairly rapid pace?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.