APPLEDORE ISLAND — It’s easy to conjure Gatsbyian images of what this place used to be, when the Appledore House was full of guests and the sound of music, the clinking of glasses and the happy voices of summer frivolity were adrift in the ocean breezes.

In the Victorian heyday of the late 1800s, the sprawling hotel on the little humpback island six miles off the Maine-New Hampshire coast was a hotbed of culture and fun. Among the annual guests was Childe Hassam, America’s best-known impressionist painter. Hassam’s most famous paintings are his series of American flags hanging in New York – Fourth of July favorites. But Appledore, with its craggy rocks and crevasses, was Hassam’s favorite place to paint.

This summer, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, takes a comprehensive look at Hassam’s work on the Maine island with the exhibition “American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals.” The exhibition is in collaboration with the Shoals Marine Laboratory, an undergraduate research facility jointly operated on the island by Cornell University and the University of New Hampshire.

The island is a very different place today than when Hassam walked its shores. Gone are the sounds of the revelers, replaced by the calls of the gulls, who nest here by the hundreds and make safe passage on the rocks difficult at best and dangerous at worst. There are structures here, to house the students and the labs. But the most prominent feature of the island is a World War II radar tower, which rises above the island’s modest elevation and is visible for miles around.

The exhibition offers new insight into a mysterious Maine island, which is part of Kittery and was explored by John Smith in 1614. Smith noted the abundant shoals of mackerel and herring, which gave the island a sustaining presence in the early days of Colonial America. Its sun-bleached rocks made a perfect environment for drying fish.

As the appetite for dried fish diminished, Appledore reinvented itself as a tourist destination. Thousands of people came to Appledore in the years following the Civil War. They explored the island’s lazy profile, frolicked in its tide pools and marveled at the sights and sounds of the Atlantic Ocean.

Hassam made more than 300 paintings over three decades on Appledore, beginning in 1882. That represents about 10 percent of his artistic output, said Austen Barron Bailly, curator of American art at the Peabody Essex. The museum is showing 42 of them, in galleries outfitted with what Bailly calls “experience pools” evocative of the Appledore environment – the sound of the ocean played through speakers, the scent of the gardens and the movement of air through the galleries created by wind machines behind the scenes. Bailly and her team installed this exhibition mindful of research that suggests people absorb the material better when they learn using multiple senses.

“We are thinking hard about how audiences are going to relate to this material and giving them the opportunity to look closely and pause,” Bailly said. “We want to capture people’s attention the way these vistas captured Hassam.”

Aesthetically and in terms of is artistic focus, Appledore was to Hassam what Prouts Neck was to Winslow Homer: inspiring, sustaining and gripping. Both men painted plein air in their respective environments at the same time, separated by a few ocean miles.

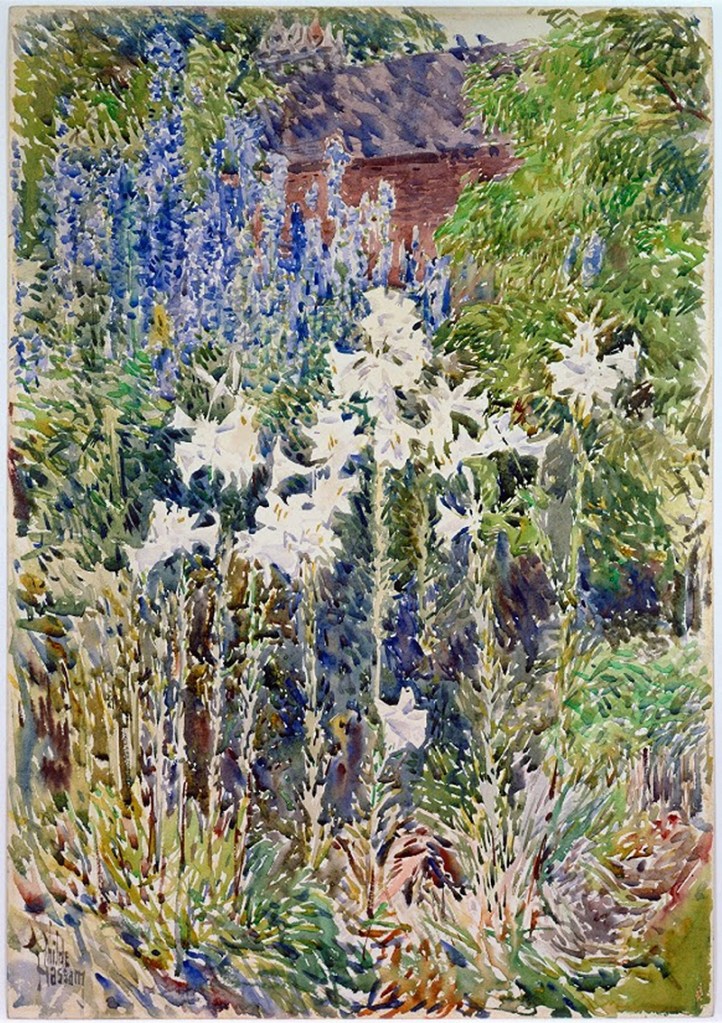

Hassam has long been associated with the botany of the island, because of his friendship with poet and gardener extraordinaire Celia Thaxter, whose family operated Appledore’s hotel. Her wondrous gardens beguiled Hassam’s impressionist senses, and he filled his canvases with her radiant poppies and summer blooms of purple, red, pink and yellow.

Hassam, who was born in Boston in 1859 and died in East Hampton, New York, in 1935, came to Appledore to work. These were working vacations, Bailly said, but he made time to socialize and was particularly fond of Thaxter, who was as famous as Hassam and more than two decades older. He admired her, and delighted in the company she kept.

Thaxter’s nearby cottage, with an enclosed porch made private by a thick veil of vegetation that she lovingly cultivated, was the salon-style gathering spot for writers, musicians and artists. In addition to Hassam, the cultural elite who made late-afternoon merry on Thaxter’s porch included writers Sarah Orne Jewett from nearby South Berwick and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who came north from Massachusetts.

From the journals and daybooks left behind, we know they sat on the porch and caroused, recounting the adventures of their days and planning their evening merriment. Drink and song were part of the daily prescription.

Hassam made paintings by the dozen. He was smitten by Thaxter’s lush gardens, which extended from the porch of her cottage down toward the nearby sea. At sunset, he moved to the hotel deck and quickly sketched on the underside of cigar-box tops the unfolding drama of the sun dipping into the sea and the horizon exploding in yellow and red. He often gave the box tops away to admirers, deftly showing off his skills with the flair of a showman.

The marine lab has restored Thaxter’s garden, using her garden plan and Hassam’s paintings as guides, as well as a few plants that have survived since Thaxter’s day. The resort hotel used her flowers in its arrangements, and the garden served as muse for her book, “An Island Garden.” The garden today remains true to her vision from a century-plus ago, and it is open for tours.

Hassam stopped coming to Appledore for five years after Thaxter died in 1894. The island held less appeal to him without her presence. He returned in 1899 and remained faithful to Appledore each summer but one until 1916, two years after a fire burned the hotel and ended the island’s tourist era.

Hassam used the island as a lab. He pushed himself artistically and personally, traveling to the hard-to-reach and dangerous places of Appledore and making paintings “of the exceptional, the exquisite, rare and unusual Atlantic island” that are useful to scientists who study the island today, Bailly said.

“So much has changed, but we can still find Hassam’s Appledore,” she said.

That is especially evident on the rugged northern and eastern shores, which seemed to hold the most interest to Hassam. “The South Gorge, Appledore,” an oil painting from 1912, is a near-perfect rendering of the rocks today.

Hassam’s paintings are precise and accurate, and his attention to the island’s geological and natural details was meticulous, said Jennifer Seavey, the lab’s executive director. Researchers use his paintings to measure change at Appledore over time.

They determined that Hassam made the painting “Moonlight” either during the overnight of July 9-10 or Aug. 8-9 in 1892, based on his depictions of a full moon and a spring tide, as well as other atmospheric conditions. They use those paintings to compare sea levels today to measure sea rise and other changes in the tidal zones, Seavey said.

It’s remarkable how closely the rocks in his paintings match the actual rocks today, she said. In some instances, Hassam calibrated his brush strokes to mimic the texture of the rocks he painted. “He is right on,” she said. “There is a lot of biology in his story.”

The scientists respect that, because it demonstrates his attention, his power of observation and his reverence for his subject, Seavey said. From the museum’s perspective, it’s rewarding to work on an exhibition that’s useful to people beyond those who might visit the museum, Bailly said. It’s exciting to think about using art to help science, she said.

“We now have a different language at our disposal to talk about landscapes and seascapes. We don’t have to use art history terms. We can use descriptive language about what he is painting,” she said. “Those rocks or those geological features – the times of day, the weather patterns, color patterns – are relevant to people outside of our little small field.”

Hassam’s paintings of Thaxter’s gardens are widely known and were the subject of a comprehensive 1990 exhibition, “Childe Hassam: An Island Garden Revisited,” which showed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. It got a lot of attention and included a well-researched book that documented Hassam’s early years on the island.

Less examined are the paintings that Hassam made elsewhere on the 95-acre island, mostly after he returned in 1899. The Peabody Essex show includes both garden paintings and post-Thaxter Appledore paintings. Hal Weeks, the former assistant director of the lab, co-wrote an essay about Hassam’s scientific accomplishments for the catalog that accompanies the Peabody Essex exhibition.

The island today is different than when Hassam painted there, of course. Despite the constancy of Hassam’s paintings, time does not stand still. A century ago, it was mostly barren, bereft of trees, a result of human activity. After the fire and the demise of the Gilded Age, the island returned to a natural state.

It became a quiet place again, except for the gulls. Today, black backed and herring gulls rule the place, and they are violently protective of their nests during the late spring and early summer. Seavey said that if Hassam returned to Appledore today, he wouldn’t stay. The gulls wouldn’t let him close to his favorite painting spots.

The hotel is gone, and so are Thaxter’s home and porch, save for a few remains of the foundation. There is talk of restoring the porch, to allow Thaxter’s garden to grow back to the way it was 120 years ago. If that happened, the heartbeat of the Appledore art colony would return, joining the hops, snow drops and hollyhocks that remain from Thaxter’s day.

Portland writer Caleb Mason spent time on Appledore many years ago, researching his book, “The Isle of Shoals Remembered.” Mason based his book on an original handmade daybook from 1900 that was given to the musician William Mason, a relative of the author. The pages include Hassam drawings, Edward MacDowell musical inscriptions and an entry from Helen Keller.

Caleb Mason retrieved the book from a relative’s trash and spent years researching the Appledore art community.

Presumably, William Mason was among the musicians who played the piano in Thaxter’s salon in the late 19th century.

Close your eyes, and you can almost hear the music, the laughter and the late-afternoon toasts of a community of friends, lost in the fog.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.