The Vollard Suite is the primary source of the libido-soaked line-drawn imagery we associate with Pablo Picasso. The suite is a series of 100 prints commissioned by Picasso’s art dealer, Ambrose Vollard, who gave the young artist his first show in 1901. Picasso produced 97 of the plates between 1930 and 1934, punctuating them with a trio of portraits of Vollard in 1937.

Vollard hired Richard Lacouière to print the suite in 1939, but because of morbid timing – Vollard’s death in a car accident that year and then World War II – the prints largely did not begin to enter the market until the 1950s. It had been Vollard’s practice to publish artist books of 250 prints along with a deluxe edition of 50 signed prints; this was such a project, but it remained permanently interrupted.

Peter and Paula Lunder recently gave an extremely rare complete deluxe set – one of only eight printed by Lacouière on extra-large Montval paper that were all signed by Picasso – to the Colby College Museum of Art, where about half of the prints are now on display.

In the context of Colby’s deep and rich Lunder-supported collection of prints by Rembrandt, Whistler, Durer and innumerable others (fine examples of which can be seen just a few rooms away from the Picassos), the Lunder set, which has never been exhibited in public, is an extraordinary rarity on an international scale. (London’s British Museum announced its set was one of the museum’s most significant acquisitions of the last half century.)

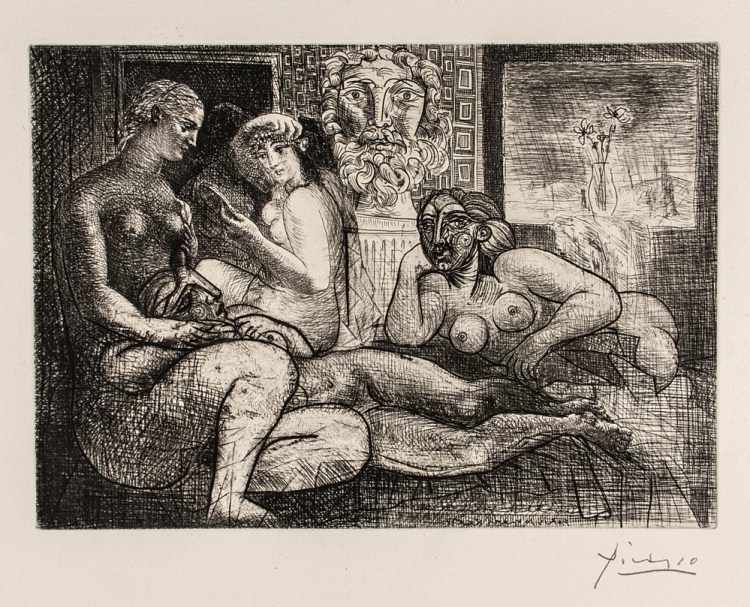

The mythological and classical appearance of the repeated characters in the Vollard Suite – a minotaur, a sculptor, maidens, muses, art – suggests narratives not unlike those depicted by Picasso in his suite of prints based on Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” which he had completed before beginning the Vollard Suite. Those crumbs, however, lead away from the loaf: There is no underlying narrative. And you aren’t going to see the revolutionary aspect of Picasso’s work by following well-worn trails. Projecting a story onto the sculptor, his muse and model and the debaucherously tragic transformation of the minotaur treats the images as illustrations of a largely surmised story based on psychobiography and hindsight. These works did not illustrate a pre-existing story.

Pablo Picasso, “Taureau ailé contemplé par quatre enfants” (“Winged Bull Watched by Four Children”), 1934

Picasso’s use of multiple styles in one image, for example, is not answered by story. His 1934 etching “Two Catalan Drinkers” (Picasso didn’t title the prints, so try not to read too much into the titles), shows two men rendered in very different styles.

One is a simple outline on the white paper while the other is ornate, detailed and decorated with a line-darked sense of inky, voluminous mass. The difference is not a question of story, but of mode.

We now think of “mode” as the difference between major and minor keys in music. In the arts, a common distinction has been between the two types of Classicism: the ordered Apollonian and the (drunkenly) wild Dionysian. The classicist’s classicist Nicholas Poussin (1594-1995), for example, made the distinction between such modes the basis of his work.

With Postmodernism, we now accept the idea that artists can mix styles within an image as they please, but that was not the case until Picasso and his partner Georges Braque opened that door with late Cubism (1912-1914). The artistic context of the moment when Picasso made the Vollard Suite was Surrealism.

Picasso was on the edge of the Surrealist club, and while not an official member, he did participate in some of their activities and in many ways was truer to Surrealism’s tenets than many members.

Surrealism’s self definition was “automatism,” creating works unguided by a pre-ordained plan or conscious control, working, if you will, without thinking.

The idea is that subconscious impulses would surface if allowed. And Freudian impulses – in which the Surrealists believed – are libido-driven: desire, fear, creation, destruction, fantasy and so on, unencumbered by reality and freed by dream logic.

We can parse the characters and the semblances of story, but even this process is directly inspired by Sigmund Freud, as psychobiography – the means by which meaning is typically assigned to the Vollard Suite: the role of Marie-Thérèse as Picasso’s model, muse and lover; the trajectory of that relationship; and its effect on Picasso’s marriage. But following this path generally excludes the idea that Picasso, who was quite aware of Freudian theory, was actively examining his own psychic life of dreams, fantasies and fears through Surrealist processes.

Picasso’s personal iconography is rich and quite relevant, and his development as a printer is on view within this series as earlier works are dominated by simpler neoclassical line-driven etchings before expanding into various processes including dry point and aquatint, the most famous (and accomplished) example of which is the “Blind Minotaur Led by a Girl Through the Night.” But the subjects themselves, such as this one and the repeated theme of the minotaur uncovering women as they sleep, make the case that the suite is more of a dream diary than anything regarding Picasso’s conscious intentions.

These works embody imagination in the classic sense of the word. And to look at them this way allows the viewer to stand beside Picasso and share his wonder, excitement and bemusement during the process of self-discovery. This is not an unusual thing for Americans: It is the basic tenet of Abstract Expressionism. And what we are seeing with the Vollard Suite is the birth of what becomes the art of America after World War II.

There was no Abstract Expressionist painter more popular or influential than Willem de Kooning, and once you consider his “Woman I” (1950-52) and Picasso’s Vollard Suite in light of each other, it is difficult to disconnect them.

This is where the titles, for example, are a barrier. A trio of three powerful prints in contrasting media and styles is exciting in terms of printmaking, but the works are titled “Rape” and seeing that title on adjacent wall labels takes the viewer’s mind somewhere it doesn’t want to go.

But if we consider Picasso wasn’t choosing this imagery but, rather, finding it – boldly and honestly – then instead of mere moral depravity, we are witnessing a process of integrity.

We have ingrained Freudian ideas such as the subconscious, libido and dream logic so deeply that it’s hard for us to recognize they were revolutionary before “surreal” became a common word. Picasso, too, was so influential that it’s hard for us to see what art looked like without his effect.

What makes the Vollard Suite particularly great for us, the viewers, is that it is broad enough to provide its own context: 100 Picassos sounds impressive because it is.

But while it is worthy enough to analyze on historical, museological, technical and thematic terms, we should be open to the Vollard Suite’s irrational paths, those foibled, sometimes titillating and often ugly-edged places where our humanity folds like melted clocks and bubbles up to the surface.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.