“O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York” at the Portland Museum of Art was originally organized by the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, around the soft logic that these Modernist female painters all worked in the city between about 1910 and 1935.

Gathering these four intensifies some tricky issues about proximity and access: One, Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944), was a wealthy socialite spinster and the others were all married to historically important male artists. Mainer Marguerite Zorach (1887-1968) is well known to audiences here – as are her husband, William, and daughter, Dahlov Ipcar. Helen Torr (1886-1967) was married to American painting pioneer Arthur Dove. And Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) no longer needs an introduction.

A lesser known story about O’Keeffe, however, illustrates the conundrum of “Women Modernists.” During the mid-1970s when O’Keeffe was the most famous female artist in America, she refused to loan work to the major exhibition “Women Artists: 1550 to 1950” surveying about 150 of Western history’s most important female artists. By that time, O’Keeffe was not as willing as she once had been to let herself be marketed as an artist defined by gender.

Curator Linda Nochlin, a feminist art historian, was not persuaded by O’Keeffe’s request to disassociate herself from the show. Nochlin included O’Keeffe by borrowing her work from another source.

“Women Modernists” is an echo of that conundrum. It is a show of female artists who were not comfortable being primarily identified by their gender and pigeonholed as “women artists.”

We could discuss data, like how less than 5 percent of the works in the grand 2004 reboot of the Museum of Modern Art in New York were made by female artists. But the problem is more complicated: How do we reconcile the historic societal bias with contemporary practices and conversations? How do we talk about female artists of the Modernist moment? After all, the interest in and relevance of artists change over time. The trick may be to remember that we aren’t trying to change the past, but rather our own contemporary perspectives.

Did Nochlin do the right thing?

You bet. And so did O’Keeffe. Art historian Nochlin and artist O’Keeffe had very different but valid perspectives. Curators Ellen Roberts of the Norton and Jessica May, who installed the show at the PMA, are doing the right thing now by furthering the conversation started so long ago.

And yet, in “Women Modernists” it is O’Keeffe who ultimately triumphs, while the true beneficiary is the public. It’s also a triumph for Torr and Zorach. My problem with Stettheimer is simply that I don’t like her work. I find her paintings affected, entitled, coloristically overbearing (was she allergic to blue, or what?), narcissistic and poorly painted, but I acknowledge it must be an issue of taste, because many people I know fall to pieces over Stettheimer.

It’s easiest to let O’Keeffe lead the way, and the Portland Museum of Art does just that – with five of her six iconic “Jack-in-the-Pulpit” canvases on loan from the National Gallery. The label copy indicates the show was organized biographically by the Norton, but any semblance of organization immediately dissolves here. On the strength of the work, however, we hardly care. (Still, we all deserved to see how Stettheimer’s “eyegay” 1921 “Still Life with Flowers” would have looked next to O’Keeffe’s sexually crisp florals.)

In general, May’s scripted lack of organization wisely avoids uncomfortable comparisons, like if the Christmas-light-bright self-portraits of Stettheimer had been with the pair of devastatingly honest self-portraits by Torr.

Stettheimer’s “Jenny and Genevieve” (c. 1915) features a high society woman brooding over fruit served by her African American maidservant. The social narrative crackles uncomfortably. The label makes it worse. It notes how the scene “evokes Stettheimer’s own position, constrained by a well-bred existence that prevented her from having the time she wanted for her art.”

If I am not mistaken, “well-bred existence” means “rich socialite.” O, to envy the maidservant, who is free from such woes! (I am starting to remember why I don’t like Stettheimer.) This is one of the few worthy, if horribly fumbled, feminist narratives in the gallery: These artists simply didn’t have enough time to make art. It’s an important point about female artists, but it gets mangled here.

Nearby, a label tell us about Zorach’s trip around the world from 1911 to 1912 and then explains she switched to textiles because she didn’t have time to paint. But looking at the gorgeous “Tree of Life Coverlet” Zorach embroidered by hand leaves no doubt such work took far, far more time than painting.

And while O’Keeffe’s star power has undeniable appeal and Stettheimer’s is undeniably loud, it’s Torr’s story that resonates most sympathetically and Zorach who makes the strongest case as a pioneering artist. Torr, a devoted wife to Dove, was wracked by self-doubt fueled by what appears to have been a glass ceiling that ultimately constrained her like a bell jar.

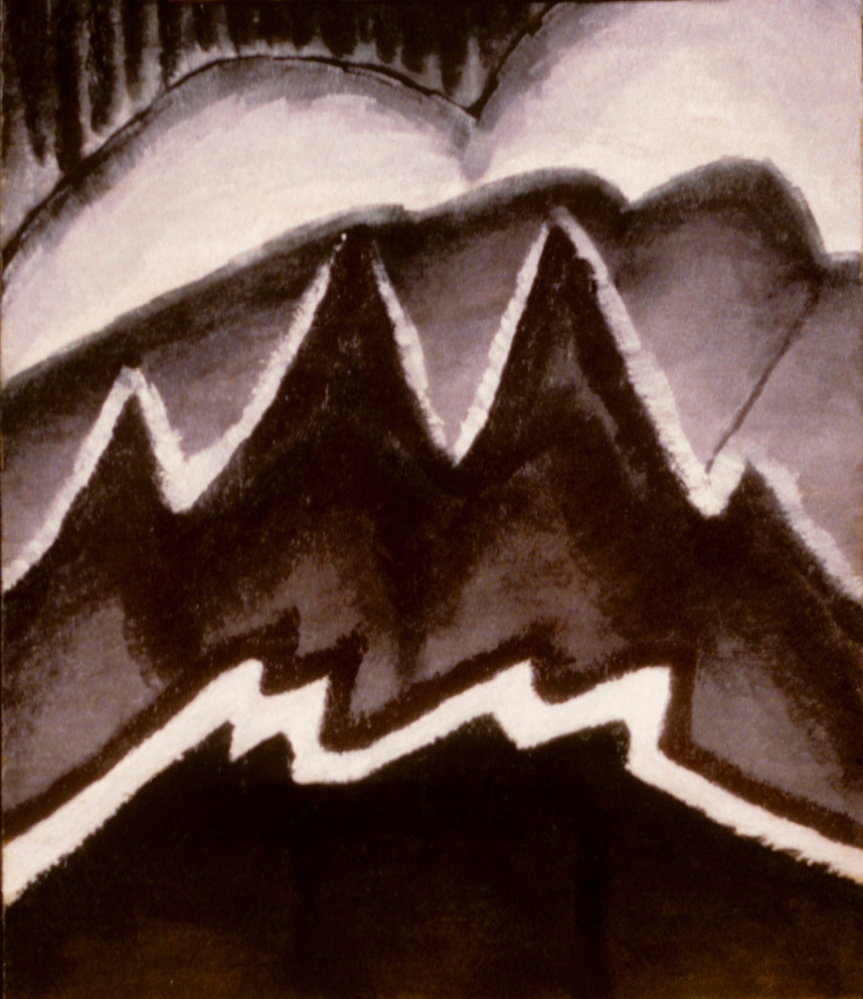

Torr’s story is tender, tough and understandable. Her paintings often fall in the realm of Lois Dodd’s intelligent spareness. Some, like “Mountain Mood” (c. 1923) and “Evening Sounds” (c. 1927), flash with undeniable brilliance. Maybe she stood in Dove’s shadow, but she was doing more than just holding him up. Torr’s “Purple and Green Leaves” (1927) is a great work of American Modernism regardless of context.

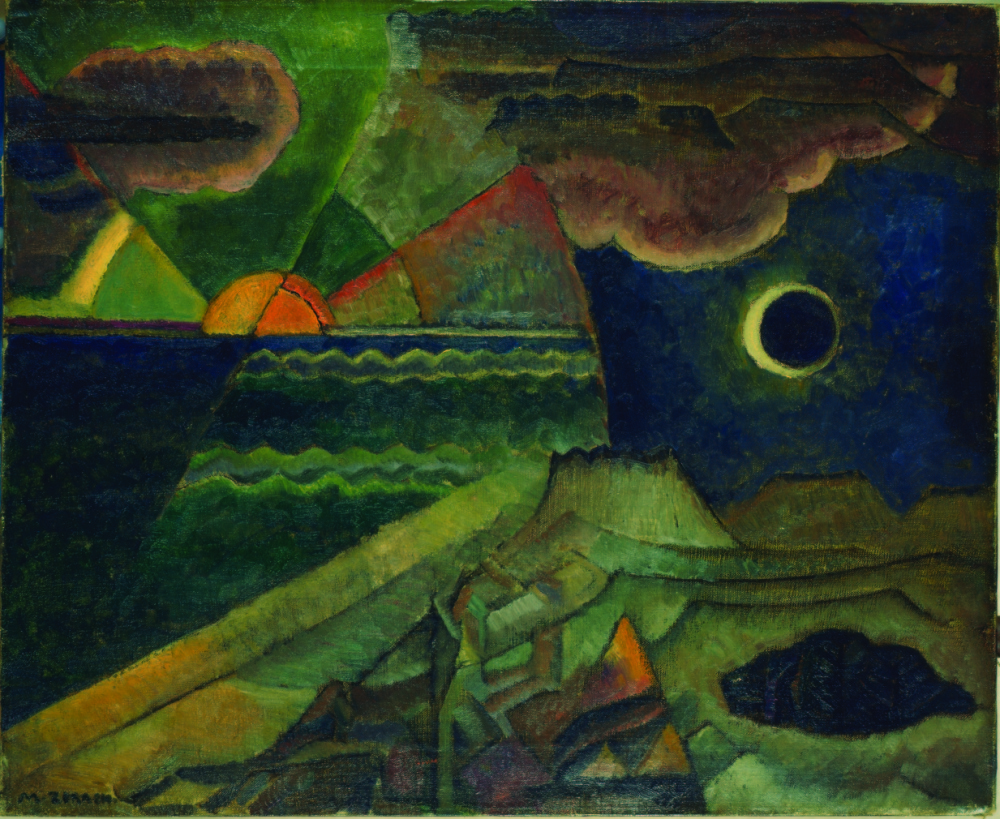

Zorach’s Fauvism-fueled painting appears prescient – concurrent to and following the seminal 1913 Armory Show that delivered full-blossomed Modernism to America. Her cubist cobbler “Justin Jason,” seen in profile plying his craft in his shop window, is a high point of Cubism. Her “Provincetown, Sunrise and Moonset” (1916) matches Marsden Hartley’s density of form and John Marin’s sectional intelligence. It sets a high water mark for American early Modernist landscapes.

Zorach’s paintings make her case far better than I can. This is true of all four artists. Seeing “Women Modernists” is exciting not because the artists are women, but because the art is exciting.

We can see why O’Keeffe was willing to let Steiglitz market her art as essentially feminine before she changed tack and sought a place in history not solely defined by her gender. To understand our culture’s history, we cannot forget the challenges faced by any identifiable group. But that doesn’t mean we can’t solve the problems they once faced.

“Women Modernists” is a good reminder why this is the right thing to do. It has the taste of triumph.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.