Small galleries dot the Maine coast. Poking out from among these are more than a few notable gems. The Islesford Dock Gallery on Little Cranberry Island is among them. The small dockside space this summer includes the presence of strong and well-known artists like Henry Isaacs, Judy Taylor and Robert LaHotan, but the strength of this gallery goes even deeper.

You can see LaHotan’s and Isaacs’ works on the mainland right now, too. LaHotan’s Klimt-like flickered spray of brushmark landscapes are featured in a solo show that just opened at Yvette Torres Fine Art in Rockland. And Henry Isaacs’ brush-luscious, smartly dappled and supremely affable day-bright quilted landscapes headline his August solo show at Gleason Fine Art in Boothbay. Still, Isaacs has 15 works now on view at the Dock, a substantial body of work.

Taylor is a widely shown artist who had a moment of fame when Gov. Paul LePage took the unprecedented step of taking down her Maine labor history mural (which was paid for primarily by federal funds) from a state building and hiding it in a closet.

Much of the gallery’s work would satisfy anyone looking for the standards. Michel Booz’s “Acadia Dock” is a reminder that watercolor in the hands of an architect is a sophisticated medium. Maja Paumgarten’s still lifes channel a satisfyingly thick bit of the former Maine island artist Fairfield Porter. Christine Lafuente’s still lifes and landscapes are excellent vehicles for her lithe brushwork.

What is particularly notable about the gallery is not the strength of the most recognizable artists or the brush-driven traditionalists, but rather the diversity and range of the roster as a whole.

Artists like Lesia Sochor and Kayla Mohammadi are among the edgiest female contemporary artists in Maine. Sochor’s chine-colle dress pattern-based paintings dig deep and subtly towards issues and ill-placed ideas about the cultural battleground of women’s bodies.

One, featuring a quiet chorus of Vogue magazine logos, references the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s masterpiece, John Singer Sargent’s “Portrait of Madame X.” Sochor’s image challenges the viewer to remember and reconsider Sargent’s image of his model, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, from a dress design. It’s an exciting but dizzying prospect: For the time, in 1883-1884, it was a extremely risque image of an extraordinary model. And we have to ask ourselves about her wasp waist, for example (very tricky, but possibly far more interesting, if you do this from memory) and whether this was a possibility of the body-squishing technology of the time, or if it is an example of idealizing the model, which we now see through very new lenses, aware and concerned about topics like young women’s body issues.

Personally, I am enthralled by the Sargent, and so find the Sochor exciting and engaging. Her approach, however, made me question both the content I have taken for granted and that which I might have overlooked.

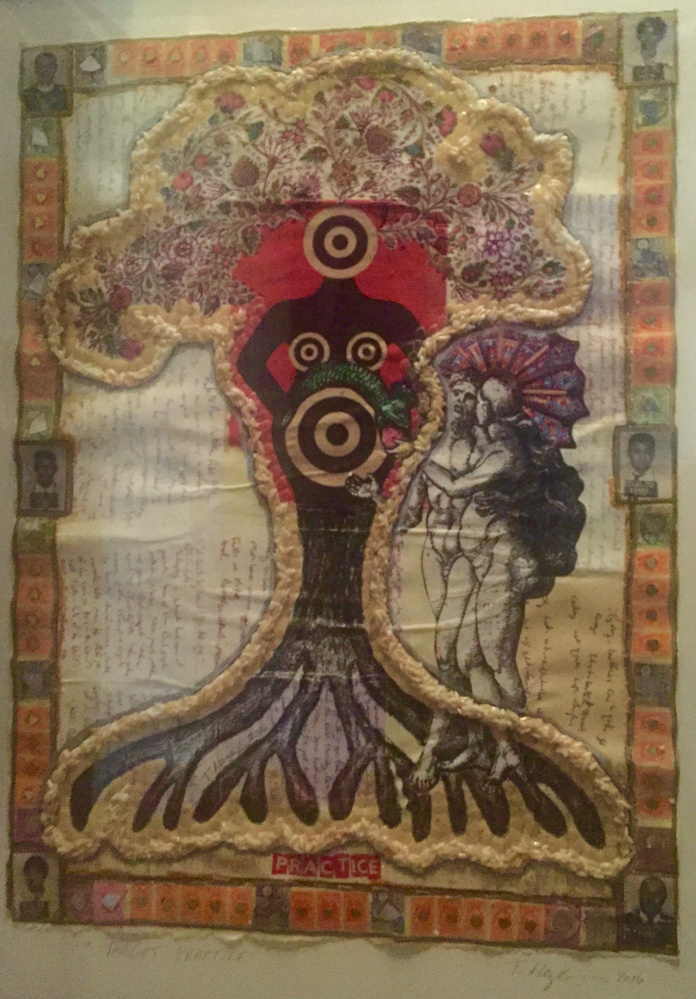

Thom Heyer of New York is a summer resident of Islesford. His dense identity-oriented collages have a poster-like presence. The center of “Target Practice,” for example, features an abstracted, curving female form with a bullseye target at its middle. The surrounding work is dense with concerned bits: stamps, costume jewelry hearts and so on. What defines the piece is a series of early-1960s mugshots of arrested civil rights activists, including women and priests whose presence makes it clear we’re looking at activists rather than hardened criminals.

Heyer’s work does not preach. Instead, it positively pronounces engagement and announces his support. His homegrown aesthetic backs this up as an individual’s scribbled perspective rather than the anonymous volume of well-honed and polished mass ideological products.

Before visiting the Dock, I had only seen Kayla Mohammadi’s work in the context of purely contemporary art idioms. She is a strong painter whose work reveals both reductive Nordic design elements and the decorative complexities of Persian carpets and miniatures. While this might seem like an unusual fit with Maine painting, think again. Her work uses a denser, darker and richer palette than what we typically associate with Maine painting, but it has precedents that reach back to Marsden Hartley.

In fact, traditional Maine painting generally has been recognizable by the flurried surface activity of mark making’s relationship to the solid and simplified forms of the pictured objects. From this perspective, it’s less surprising that Mohammadi’s works line up, not only with the odder edges of Maine painting, like the work of the late Robert Hamilton, but with Isaacs’ idyllic patchwork landscapes or Taylor’s flattened gouache coastal scenes.

An interesting aspect of Mohammadi’s work is its tilt of the hat to French “Orientalism.” Her “Delacroix’s Morocco III” comes to us as Matisse’s interpretation of Delacroix further interpreted by Maine painters like Hartley, the Zorachs or Louise Nevelson. Whatever her inspiration or intention, these pieces work surprisingly and satisfyingly well in this painterly setting.

The Dock is a seemingly very casual place. In fact, one of the most notable presences in the gallery is a series of brightly beaded animals made by micro-economy artists in South Africa (each is “a unique artwork made by disadvantaged people in the townships of Cape Town”). These playfully channel Dahlov Ipcar, but they do not add a commercial flavor to the gallery. Quite the opposite: the beaded works further the gallery’s fine and fitting community ethic.

It is this sense of community that defines many of the coast’s hidden gallery gems, no matter how small or out of the way, including Turtle Gallery, Littlefield, Mathias and others. Islesford Dock Gallery is in a charming and beautiful place that is only accessible by ferry, but it is very much part of the heart of Maine.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.