EAST BOOTHBAY — With their reputation for sliming ponds and rendering beaches unusable at the height of summer, algae will likely never top any list of plants with widespread commercial or culinary appeal.

But for a team of researchers at a Maine laboratory that specializes in the microscopic aspects of the world’s big blue oceans, algae could hold the keys to some of the biggest scientific – and commercial – quests of our age.

Stuff like finding blockbuster cancer drugs, figuring out how to make farm-raised seafood more sustainable and developing naturally growing biofuels capable of offsetting or even replacing our finite supply of fossil fuels.

The key to this versatile little aquatic plant is its ability to grow like, well, green slime in a stagnant pond during the summer heat.

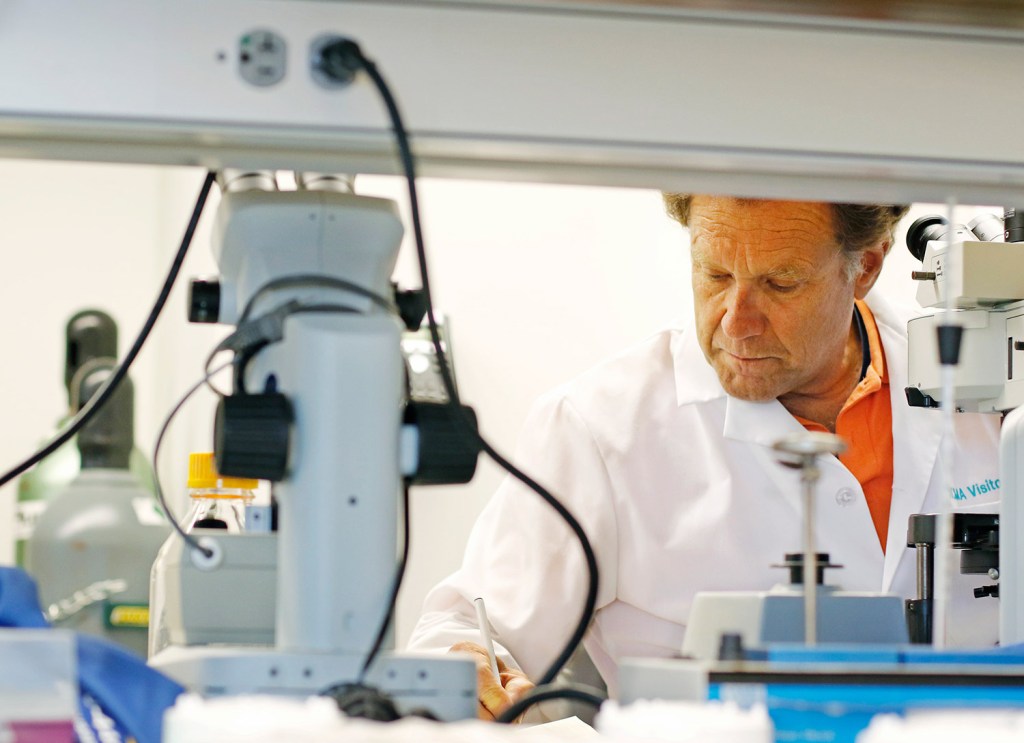

“The funny thing about algae is they are immortal unless you kill them,” Michael Lomas, head of the marine algae program at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay, said with a laugh as he explained the commercial potential of algae. “As long as you don’t starve them of light or they don’t run out of nutrients for too long … they will keep growing and growing and growing.”

Bigelow’s National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota already houses the country’s official collection of phytoplankton – a designation that makes it a go-to resource for researchers around the world. But last week, crews began work on a 3,000-square-foot greenhouse that Lomas hopes will allow the center to play an even larger role in a multibillion-dollar commercial industry that, like algae, keeps growing and growing.

“Obviously we have about 3,000 strains of algae here so we are pretty good at growing them,” Lomas said. “So these services we have developed for researchers we are now (shopping) around and offering to companies.”

USED IN MANY PRODUCTS

But is there a really a market to support a $300,000 greenhouse devoted solely to algae?

Well, chances are pretty good that you, a child or a pet in your family are already unknowingly participating in the bloom of the algae industry.

The omega-3 fatty acid used in half of all infant formula, known as DHA, is derived from algae. Algae are increasingly showing up as protein or fatty acid supplements in dog or other pet food.

They tiny plants are in shampoos, vitamins, energy drinks and were hyped as the sustainable alternative to petroleum – because some strains of algae are copious producers of oil – until crude oil prices fell back below $100 a barrel. And that seaweed wrapped around your sushi roll or added to a vast array of products in the form of carrageenan or agar? Those are algae, albeit “macro-” (or big) algae.

A recent study pegged the economic value of all varieties of algae in the marketplace at $14 billion.

“That seems like a big number, but oil and petroleum is around $5.8 trillion – that’s with a T,” said Stephen Mayfield, principal investigator at the California Center for Algae Biotechnology at the University of California at San Diego. Mayfield, who is known as “Professor Algae, and his colleagues have spun off numerous algae-related companies from their research, including several that benefited from the brief explosion in energy industry interest in biofuels from algae.

More recently, Mayfield and his UC San Diego colleagues made a huge splash on social media and in national media by producing the world’s first surfboard made of algae. It is made of polymers derived from the oil of algae. Most surfboards today are made from petroleum products, which Mayfield said is antithetical to many sustainability-sensitive surfers. And Mayfield says attitudes are definitely changing when it comes to algae as not just an acceptable but a healthy food source.

“I think the dominoes are ready to fall, but the question is how big will that market be?” said Mayfield. “If you break into the animal feed market, you’re talking about billions of pounds. … It’s not like you or I, when we go to the store say, ‘Hey, honey, pick up some algae.’ But it might not be that long before that is happening.”

EXPANSION MOVES FORWARD

At Bigelow’s building located above the Damariscotta River, Lomas and the National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota team are moving forward with their expansion plans.

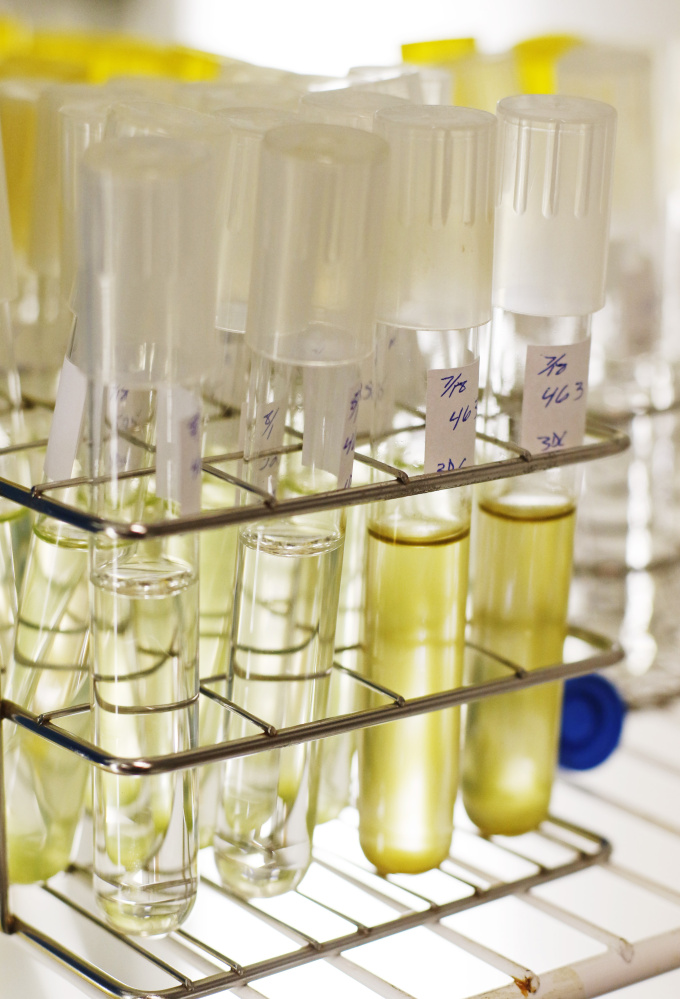

More than 1,000 strains of algae in various shades of green, yellow, brown and red – indicators of their chlorophyll levels and a hint to their ecological niche – are housed in test tubes or flasks kept in incubators the size of commercial refrigerators and walk-in freezers. Another 1,000-plus strains are kept in cryogenic freezers chilled to minus 196 degrees Celsius, allowing the lab to keep the algae alive in suspended animation without the attention required of constantly dividing strains of active algae.

But test tubes and flasks aren’t efficient for commercial-scale growth. So staff built a mini-greenhouse in the center’s basement capable of growing algae in four tube-shaped towers, each capable of holding 500 liters, or 132 gallons. Passing the cloudy, bubbling water through a centrifuge-like separator typically yields about 18 to 22 pounds of an “algal paste.”

Once constructed, the $300,000 greenhouse will be large enough to accommodate 50 such algae production plants.

“Four is good and they can be used for a lot of things,” Lomas said while standing near the mini-greenhouse. “But it is definitely not at the scale we would need for commercial production.”

The center already works with numerous private companies.

One firm, Field Energy LLC, contracts with Bigelow to create a type of algae it is using to attempt to improve the quality of fatty acid products. The center also supplies the type of glow-in-the-dark algae responsible for the phenomenon known as bioluminescence to a California company that creates educational kits for schools. In another example, center staff sorted through hundreds of strains of algae to find a variety that produces an anti-cancer agent that a company was hoping to produce from algae rather than sawgrass.

The 3,000-square-foot greenhouse will allow the center to take on more contract work, providing an additional source of revenue to replace the steadily declining supply of available federal research funding. Lomas said he also hopes the larger-scale facility will become “a flywheel that drives innovation,” working with companies in Maine and around the world. Farming of kelp, seaweed and other macroalgae is a growing industry in Maine.

POTENTIAL PHARMACEUTICAL USES

Algae are also a prime candidate for a more sustainable source of the omega-3 fatty acids in the protein fed to Atlantic salmon and other farm-raised fish in Maine and Canada – protein now largely sourced from other fish. And then there are all of the potential uses – particularly in pharmaceuticals – of algae that have yet to be discovered from the 3,000 strains kept in incubators or freezers in East Boothbay.

“We know a lot, but there is still a lot we don’t know” about algae, Lomas said.

Back in California, Mayfield said algae’s growth in the marketplace is often tied more to social acceptance than to technological ability. Many companies have proved they can produce algae-based products. The challenge now is to produce a product that people want and that will compete price-wise with whatever it is replacing.

But Mayfield sees the shift in his own students of the millennial generation, one of whom recently showed him a can of an energy drink proudly declaring that it was made with red algae. That algae turned out to be the 20th, or so, ingredient in the drink, meaning it had more food coloring in it than algae. But the marketing speaks to the changing attitudes and tastes of younger generations who, in turn, often inspire older consumers.

“If it’s in big letters – ‘Contains red algae’ – then clearly that generation has gotten over the ick factor,” Mayfield said.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.