Jaime Higgins had spent the past few years learning about the harshest aspects of drug addiction, driven to understand and help her brother Devon free himself from heroin’s grip.

As a coordinator of Operation HOPE at the Scarborough Police Department, she had helped hundreds of other addicts get into rehabilitation programs. Still, she was unprepared for the call she got on the morning of Sept. 27.

Devon Higgins had been found dead on the kitchen floor of his Portland apartment after an apparent heroin overdose. A friend had gone looking for him when he didn’t show up for work. It had been more than a year since he got clean, and just two weeks since he graduated from Drug Treatment Court and the strict supervision and support it had provided for 12 months.

A co-worker at the police department drove Jaime Higgins to Portland. Police officers wouldn’t let her into her brother’s apartment because it was a crime scene. So she stood on the sidewalk, sobbing, surrounded by friends. Cars passing by on Cumberland Avenue slowed as drivers stared at the commotion.

“I was a mess,” Higgins recalled. “I was begging them to let me into the apartment because I didn’t believe it was him. When they finally let me inside, my foot slipped where they had cleaned the floor. That’s when I was like, ‘This is really happening.’ ”

But she didn’t really believe Devon was dead until she viewed his body later at the funeral home.

“I wasn’t prepared to see him like that,” she said. “My brain didn’t want to accept that it was him. I touched him and he was so cold. Then it was like a switch flipped inside me. All of a sudden I was numb. The crying went away and it’s like I’m living someone else’s life.”

HEROIN DEATHS RISING

Nearly a month after her younger brother’s death, Jaime Higgins is wrestling with grief and guilt that are rooted in everything she knows about the disease of addiction and everything she didn’t know about the choices Devon Higgins was making during his last days. She believes he died after using heroin for the first time in 16 months. She also believes it was laced with carfentanil, an animal tranquilizer that’s 10,000 times stronger than morphine.

“I feel like Devon would have known that his tolerance was down and he would have used the tiniest amount,” said Higgins, who is a crime analyst for the Scarborough department.

Her brother’s death comes as Maine officials anticipate a record number of overdose deaths in 2016. There were 272 overdose deaths statewide in 2015, with the vast majority related to heroin and prescription opioids, according to the Maine Attorney General’s Office. Through the first six months of 2016, 189 people died from overdoses, up from 126 in the same period in 2015. At that pace, Maine could have 378 overdose deaths this year, a record number.

Devon Higgins’ death rocked the recovery community in Greater Portland, not only because Jaime Higgins had been working hard to help addicts through the year-old police intervention program, but also because Devon Higgins appeared to be a potential success story. He had even volunteered for Operation HOPE and helped to place its 150th person into a drug treatment program.

But after he graduated from drug court on Sept. 14 and forged on without its regular counseling and drug testing, the glow of sobriety quickly faded under the strain of everyday living, his sister said. In recent weeks he had moved out of his mother’s house in Scarborough, where he had converted the garage into his living space, and he was planning to start his own masonry company with a friend.

He also was dealing with a difficult breakup with a girlfriend and with the passing of his 85-year-old grandfather, Kenneth Morse, who died July 27, exactly two months before his grandson. His sister believes it was a combination of factors that led her brother to ignore the healthy coping skills he had learned in recent months and sent him down familiar paths to addictive and dangerous behavior.

“I think it was too many losses and too many changes at the same time,” Higgins said. “He was really struggling and he didn’t share that as much as he should have. I think he was ashamed to tell me he’d already started drinking and had relapsed. He had the resources. He had the support. He should have been able to stay sober.”

DEEPLY ROOTED ADDICTION

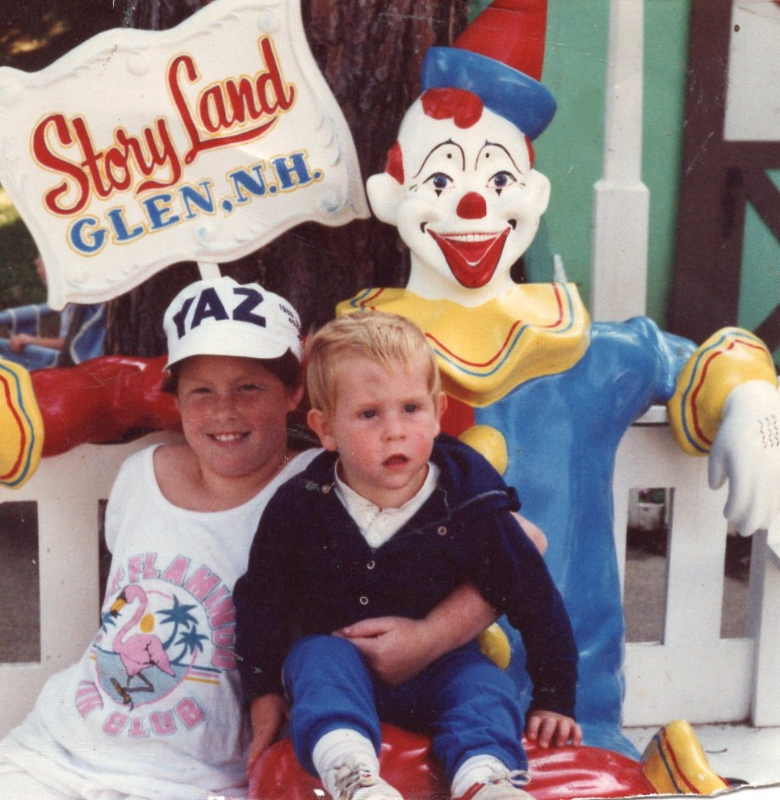

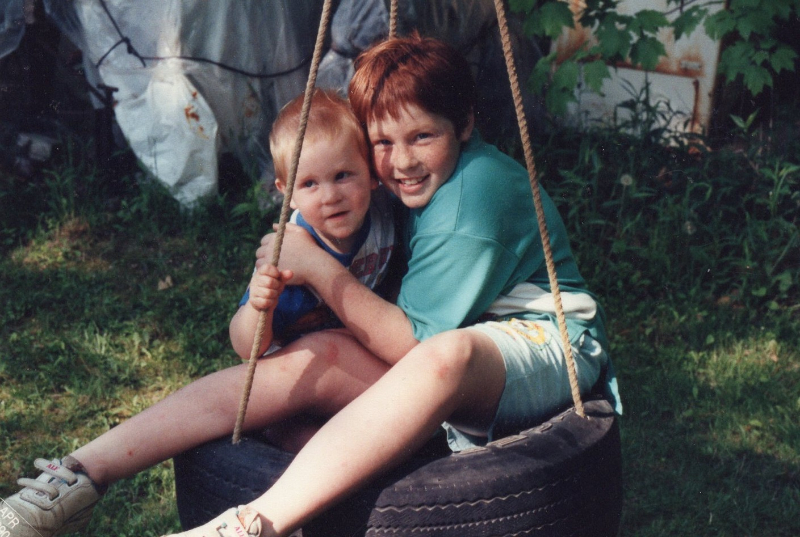

But at 29 years old, Devon Higgins had been a drug user for about half of his life. He started using drugs as a teenager who had attention deficit disorder, depression and anxiety, his sister said. He eventually graduated from marijuana and alcohol to oxycodone.

“He told me once that he immediately loved oxy because he didn’t have any pain,” she said.

He dropped out of high school, got his general educational development diploma and went to work as a commercial fisherman, an industry where substance abuse is common and illegal drugs are easily accessible, his sister said. Through his early 20s, his family saw little of him, in part because of his job. Then she spotted him about five years ago on the Portland waterfront.

He looked sickly, with acne on his face and scars on his arms. His usually muscular frame, built from years of hauling traps and pulling lines on fishing boats, was noticeably thin.

“What’s going on with you? You look terrible,” she said with a sibling’s frankness. She asked him if he was using heroin. He denied it.

“I knew he was into something, but I didn’t know (before then that) he was into heroin,” Higgins said. “At that time, I was so mad at him for putting himself in that situation. I didn’t want people to know he was an addict. I didn’t understand it was a disease.”

A few months later he called her, admitted that he was hooked and said he was ready to get clean. He stopped using and got on the waiting list for the St. Francis Recovery Center, a residential rehab facility in Auburn. But when a spot opened six weeks later, he declined it.

“He said he was doing fine on his own,” his sister said. She knew better, but she had to wait and hope that he would come back around.

In 2013, he was arrested for drug trafficking, she said. A New York dealer was selling drugs out of her brother’s Portland apartment and giving him free heroin. The sentence included several weeks at the St. Francis center. He returned home, got a job, tried to stay clean, but he eventually slipped up, violated his probation and wound up in drug court, a diversion program that favors treatment over punishment.

For a year, Devon Higgins thrived with one-on-one counseling and group therapy, as well as random drug testing and visits from his probation officer.

“That amount of structure and supervision was really good for him,” Higgins said. “He couldn’t leave Cumberland County without permission.”

It wasn’t easy. His development into adulthood had been stunted by drug use, so when he got sober, he was still a kid in many ways, his sister said. He had to learn how to tie a tie, iron clothes, open a bank account and take on many other grown-up responsibilities.

“In the beginning, it was frustrating because he hadn’t been part of the real world for a long time,” Higgins said.

‘NO ONE IS IMMUNE’

When Devon Higgins graduated from drug court, the weight of those responsibilities increased without the constant support and supervision. His sister learned later that in the weeks before his death, he had started going to a strip club with a friend, then started drinking, then started using cocaine.

“I think shame kept him from asking for help,” Higgins said. “But there is no shame in this disease. It’s everywhere, and for people to say they don’t want to pay for (rehabilitation programs), we’re already paying for it. And we’re going to keep losing people if nothing changes.”

Higgins compared her experience with her brother’s death to losing someone to suicide.

“There’s some anger,” she said. “I’ve yelled at him a few times, ‘Why the hell did you do this?’ But it’s become more a feeling of guilt, not that I really could have done anything, but that I should have checked in more, that I should have paid more attention. But he had been doing so well, I really didn’t think I had to. That’s the thing, though, you can’t really ever let your guard down.”

There’s also a feeling that, because she works in law enforcement, “this stuff isn’t supposed to happen to me, but that’s just not true. No one is immune.”

Higgins said she’s tired of some politicians who are doing just enough about the drug crisis to keep people off their backs, and others who seem to believe addicts deserve what they get.

“I don’t know how Maine came to this,” she said. “We’re better than this. When a police department has to open its doors to help people get drug treatment, something is wrong with your state.”

Higgins has been working part time as a crime analyst after undergoing major abdominal surgery in July. She anticipates returning to full-time duty in November, and hopes to resume working with Operation HOPE soon.

“It’s really hard to do that work now,” she said. “I’m sure I’ll get back into it eventually, but I feel like if I couldn’t help my brother, I shouldn’t be helping anyone right now.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.