A pair of shows at Able Baker Contemporary, “Mapping Extremes” and “Inside and Outside Landscapes,” create a powerful conversation about place, perception and knowledge using two things that might seem to point in opposite directions: maps and landscapes.

“Mapping Extremes” brings together landscape and documentary photography by Shoshannah White and Sage Lewis, with data maps by Christian MilNeil (an online content producer and data journalist at the Maine Sunday Telegram). Having seen a stunning body of White’s work from a three-week arctic on-ship residency on view at Corey Daniels Gallery, I was looking forward to this show. Corey Daniels is a gallery dedicated to formalism and sophisticated design, and there White’s photographs and encaustic works ride their visual intelligence. We feel the coolness of the melting ice forms – not the heat behind the concern.

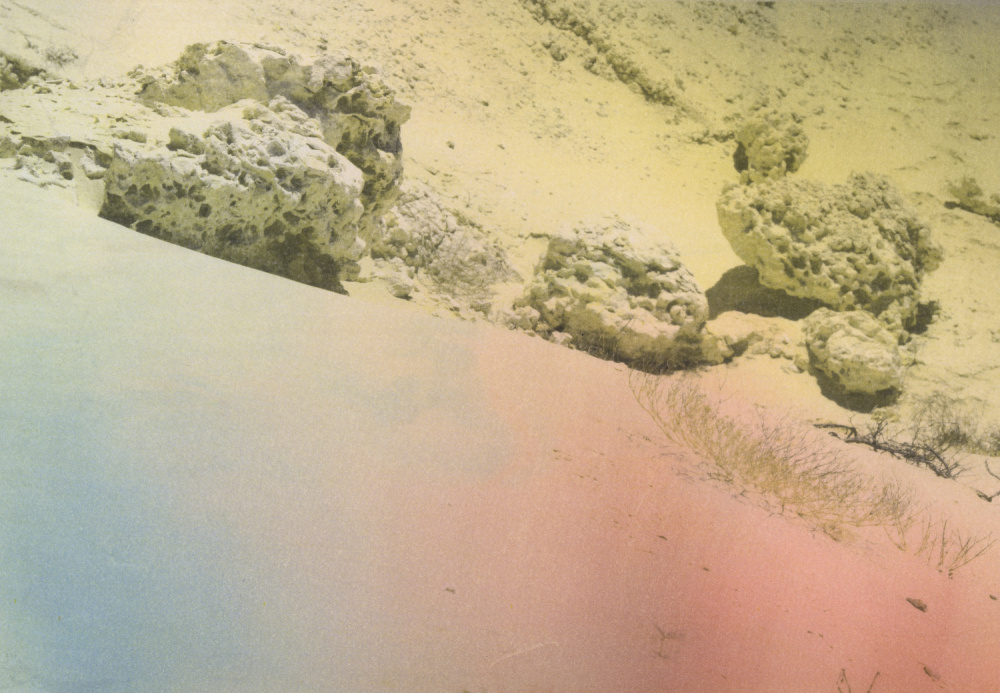

In concert with Lewis’ desiccated images of the Martian-like landscape around Qatar, also made on an art residency, White’s move into a document role. And as documents, these works press us to find a message. Once we settle on the message of climate change, the images become evidence for our own opinions.

Some of the images are structured like traditional landscapes, but these act like establishing shots for the broader project which is further clarified by a pair of MilNeil’s maps, a gif-like changing digitized globe view of earth that shows the arctic ice cap in various and dated states of retreat, and a map of oil storage tanks in Portland.

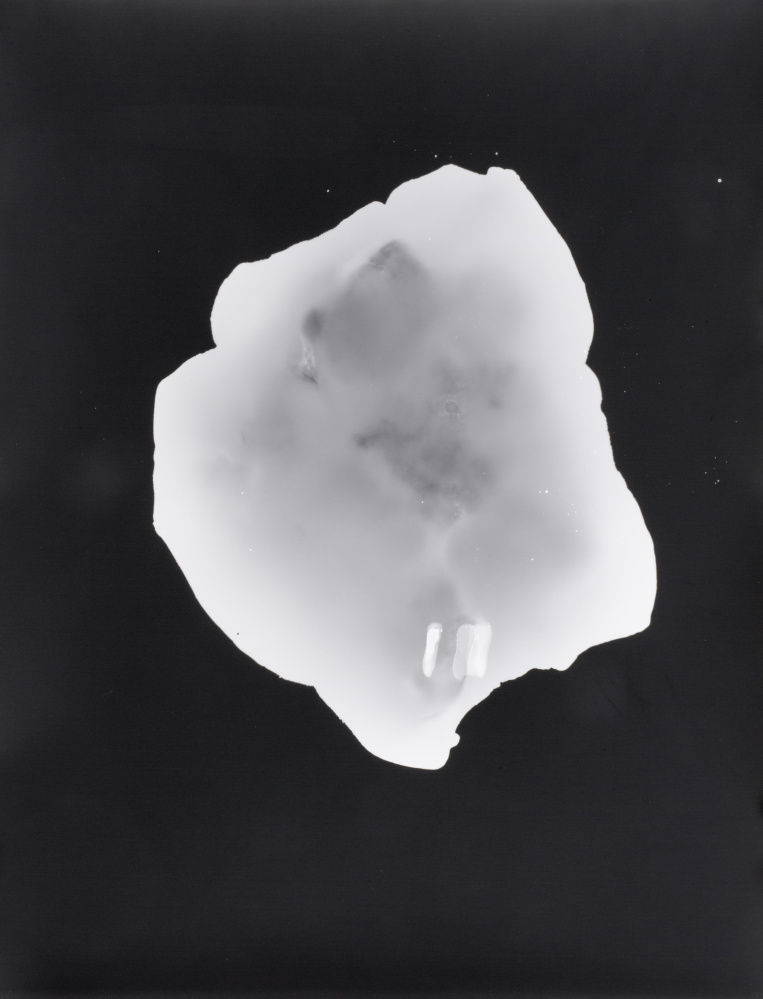

White’s work is particularly striking. “Julibukta,” a snow-white wax-covered landscape with black speckles, is a monument to brainy elegance. The “Blackstone Glacier Ice” images, made by the direct exposing of photo paper with melting glacier ice placed upon them, are exquisite objects, savvy and mysterious. Their lines are outlines, like x-rays of organisms, but with all the implications of medical perspective. While a six-panel piece is the most intriguing, a single panel work sets up an extraordinary dialogue with Lewis’s “Specimen,” a scan of a desert rock. Both works are camera-less photographs using scanner logic. Lewis’s rock image, however, emanates from the center, the point where the rock touches the surface of the scanner. White’s “Blackstone Glacier Ice #2,” on the other hand, is primarily an outline-defined flat form on the surface. While this piece has the shape of an island (islands are also defined by a flat plane of water), its transparency reveals several toothlike forms at one end, so it looks like a diagnostic x-ray, a map, if you will, of the body.

In simple terms, maps are geared towards functional data while landscapes are primarily vehicles for subjective impression. Maps depict places in data-oriented relation to each other, while landscapes depict one place from the perspective of a person present at the scene. Maps use drawing or diagram logic while landscapes use the logic of paintings: single point perspective, illusion, impression, recognizable components and so on.

Alone, the nerdy “Mapping Extremes” falls somewhere between environmental data and artistic witness. But alongside the works in “Outside & Inside Landscape,” in the main gallery, White’s and Lewis’s work engages more completely both with human subjectivity and the culture of visual art.

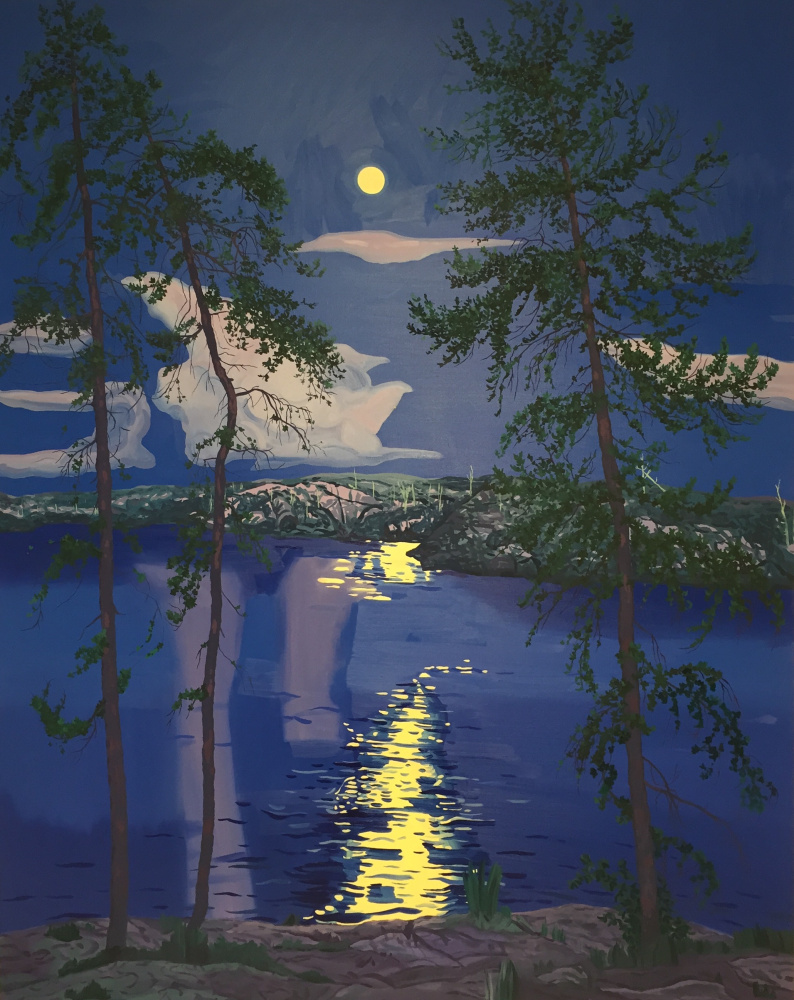

Madeleine Bialke’s two “Another East” panels, for example, depict the same stylized scene of a view from a mountain past a scraggly tree toward a lake and a vast landscape – down to the repeated bits of cloud at either side of the sliver of high horizon sky. One is a night blue landscape with the yellow dawn sky reflecting in the lake, while the other features blue sky and lake among an arid yellow landscape. From a painterly standpoint, the complementary hot/cool shift is almost a student game, but in proximity to “Mapping,” it hints at several shifting systems, subtle and serious.

Michelle Morin’s tiny “Thistle” is a decorative gem, but when compared to Hilary Irons’ “Sans Souci,” five tightly rendered cartoon-like scenes seen from a residency cabin window, it offers an extraordinary lesson in pictorial logic. The bottom frame of Irons’ scene shows cartoonishly outlined undergrowth that would sit flat if it weren’t for subtle shading in the broader areas of color. The difference between the works is that Irons, an illustrator, assumes the background to be space while Morin, a textile designer, assumes the primacy of surface in her work until she intentionally pushes it away (and then barely so) with a far off pond in the upper right corner. The result is a staticky but luscious textile-like image. Irons’ lines, stylized and bold, are geared to clear cartoon-style legibility. The outlines of her duck figure make it flat, but it pops so clearly that it throws itself into high relief from the slightly speckled background. Instead of unifying the drawing, the flat figure on the surface form makes the background feel like the far away space of a sky.

“Outside” features many interesting works that combine to present an expansive view of landscape. John Knight’s six-foot “Plantain and Fall Dandelion” is a particular pleasure, since I had thought he stopped making such large landscapes many years ago. Richard Ryan’s large Whistler-gray “River I” uses just three tones to give us a peacefully crepuscular scene decoratively tethered to the painting’s surface by a leafy silhouetted branch. Matvay Levenstein’s uses pinhole logic to swirl a dream-like cemetery scene away from its focus-weighted center. Jeremy Miranda’s diminutive, purple-gray atmospheric “Near Bar Harbor” is a plein air gem that could work in practically any gallery in Maine. Here, it bristles with a wizened visual intelligence refined by landscape painters since the Barbizon School took tubes of paint outside almost 200 years ago.

Together, these shows help remind us what we too often take for granted while looking at drawings and paintings. Sometimes (particularly with movies) it’s nice to go along for the ride and suspend our disbelief, but much of history’s best painting toggles between the image and the painting object, the landscape and the map. The literal painting with its marks and strokes and artistic skill is the map: data, traces, places and evidence. Landscapes, on the other hand, are the stuff of imagination, transportive and subjective. Maps and landscapes, however, share more than we typically notice, since they tap into our habits of experiencing the world and placing ourselves within it. Landscapes are proof that, at some point, art changed the way we see the world. Maps, on the other hand, offer proof that we have changed the world, sometimes for good, but not always.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.