“Anguish: The Grave Misgivings of Remembrance” is an extraordinarily beautiful and sophisticated exhibition. Curated by Cynthia Nourse Thompson at the Maine College of Art Institute of Contemporary Art, the show is also extremely difficult and could present an emotional overload for visitors. To this point, the show’s title gives fair warning to the depths that do not appear in an initial glance through the handsomely installed galleries.

My experience of “Anguish” was fresh and full of mystery. The forthcoming catalog is not yet available as I write this, and the show’s unadorned labels and lack of explanatory copy leave the work to the viewer’s experience. The conclusions and concerns of “Anguish” creep up with stealth and reveal themselves as emotional earthquakes. The truly haunting jolts, however, arrive as aftershocks.

“Anguish” is led by some well-known heavy hitters, including Louise Bourgeois and Jenny Holzer. Others may be unsuspectingly familiar to the local audience: The first work in the show is by Janine Antoni, whose eyelash drawings were featured in this column’s discussion of Bowdoin’s recent and excellent “This is a portrait if I say so.” Antoni’s “To Long,” an exquisitely rendered sculpture of a bone-colored mask-like half face over a pillow with a rib cage intervening. The work has many possibilities, but the notion of physical discomfort as a mediating dark factor in our dreams rings true. Antoni presents the physical body as mask, a theatrical prop that lets us pretend we can identify ourselves as something other than this mortal coil. Or, at least, we long to do so.

Antoni’s sculpture is joined in the first room by Markus Hansen’s “Romantic Sky in my own dirt,” a image of clouds rendered on plate glass in varnish and dust from the artist’s studio as well as Donna Smith’s “Cyclic,” a video of a woman, presumably the artist, seen from the upper chest up as she lies in the snow for, we assume, as long as she can stand it, about two minutes. This room is, in fact, an excellent model for the show as a whole. Victorian Romanticism, which prioritizes personal perspective over scientific objectivity, is the philosophical pedestal for “Anguish.” Like other works in the show, Hansen’s clouds are obscured by their own projected shadows. And here Smith’s suffering model, however lonely, is hardly alone.

The most obviously difficult works in “Anguish” are two of Australian artist Rosemary Laing’s photographs of women from her series “A dozen useless actions for grieving blondes.” Sobbing in teary and open-mouthed anguish, the women move us to physical response immediately instinctive beyond our practiced words. Yet, the standard portrait poses and pink studio backdrop push us to question our response to a theatricalized scene. This is where things get really complicated.

In America, particularly in the context of the 2016 elections, we have come to see news media as wrought with theater and their ability to manipulate, fictionalize and even lie. But this is also where Thompson’s deft curatorial touch is at its best: Instead of relying on the fetishizing of Victorian mourning rituals, for example, she pushes us toward rigorous cultural paths to empathy and understanding. Nietzsche is the shadow cast beyond Antonin Artaud’s “theater of cruelty,” in which the French theatrical artist sought to press for a physical or even violent insistence to disabuse us of our false notions of reality. While Artaud’s target may appear sadistic, his goal was empathy and clarity largely in line with Nietzschean perspectivism, which itself is somewhat in line with romantic and feminist notions that personal perspective is valid and important.

This is the context for Louise Bourgeois’s 2000 drypoint “Do not abandon me,” in which a baby, still attached by its umbilical cord, floats up and away from its seated mother.

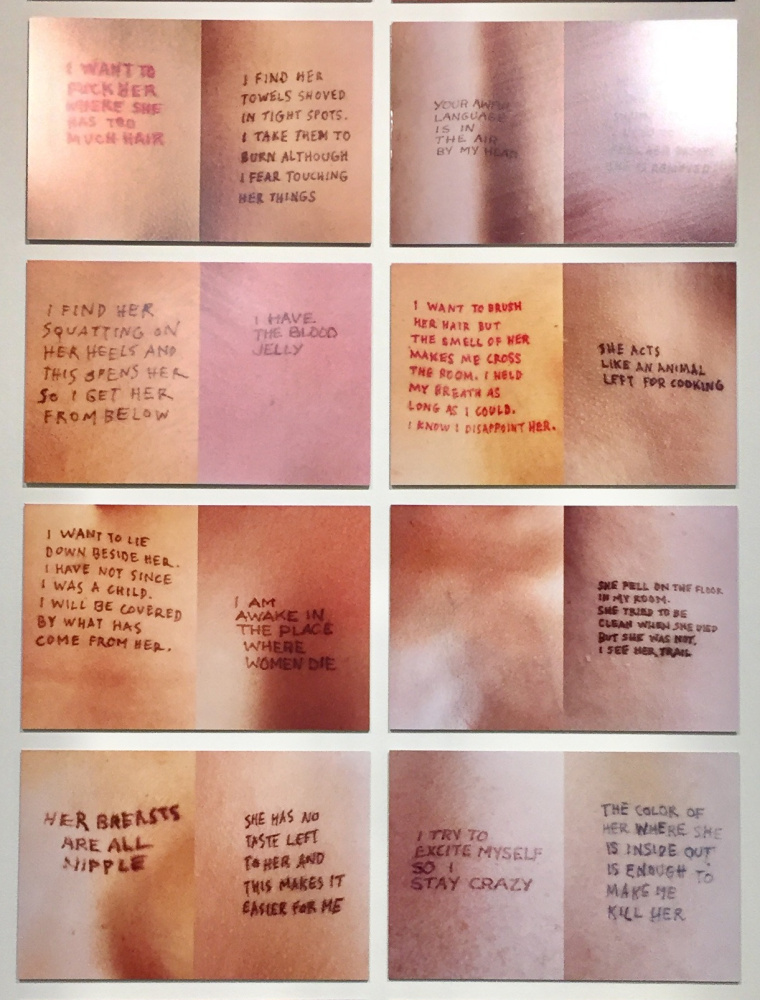

Thompson’s notions of anguish and memory arrive in full and brutal force in Jenny Holzer’s “Lustmord,” a grid of 28 photos of monstrous aphorisms written on human skin along the lines of “I HOOK MY CHIN OVER HER SHOULDER NOW THAT SHE IS STILL I CAN CONCENTRATE.” “Lustmord” is German for “lust murder,” and so what we’re reading is a murderer’s grateful acknowledgement that the woman he is raping has died during the act. This is work that Holzer made in response to violent acts committed against women by Serbs during the “ethnic cleansing” of Bosnians. This is contemporary art at its heroic best, and it is deeply and unapologetically disturbing.

In his 1887 “Genealogy of Morality,” Nietzsche described two basic types of morality that developed historically quite separately: The “master morality,” which posits good versus bad (power), and “slave morality,” which distinguishes between good and evil (altruism). Nietzsche, however, discounted emotion and understood any specific culture as the product of the struggle between these two perspectives. By positing power as an unchecked platform for abuse, Thompson’s “Anguish” seems to take a clear position in this struggle. She may not like Nietzsche, but she appears to accept his terms and their role in culture.

Much of the work in “Anguish” is easy to follow and very easy on the eyes. Piper Shepard’s “Only Their Silhouettes” is a gorgeous black floral screen of handcut muslin that softly echoes the shadows of the long lost. Roberto Mannino’s model of memory “ADRIANITE” is a small graphite frame from which we assume an image (of Adrian?) was torn long ago. Carson Fox’s “Hair filigree” is a large, decoratively indulgent wall hanging (again with the projected shadows) of human hair (to which it’s hard not to respond physically) hinting at loss, memory and the physical traces of human experience and our responses to them. The art backdrop of “Anguish” is craft with its echoes of women’s piece work practice, anti-establishment institutional positioning, and the DIY logic of personal perspective. Thompson herself has recently taught at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle. Craft, in this context, is not art-lite, but a powerful subversive current.

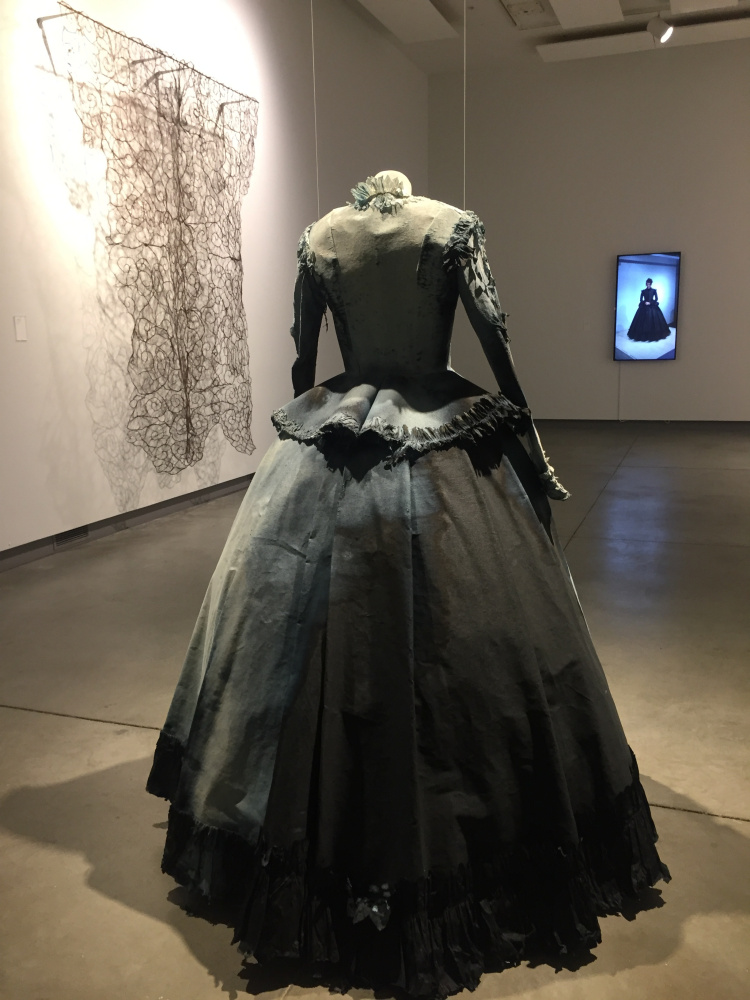

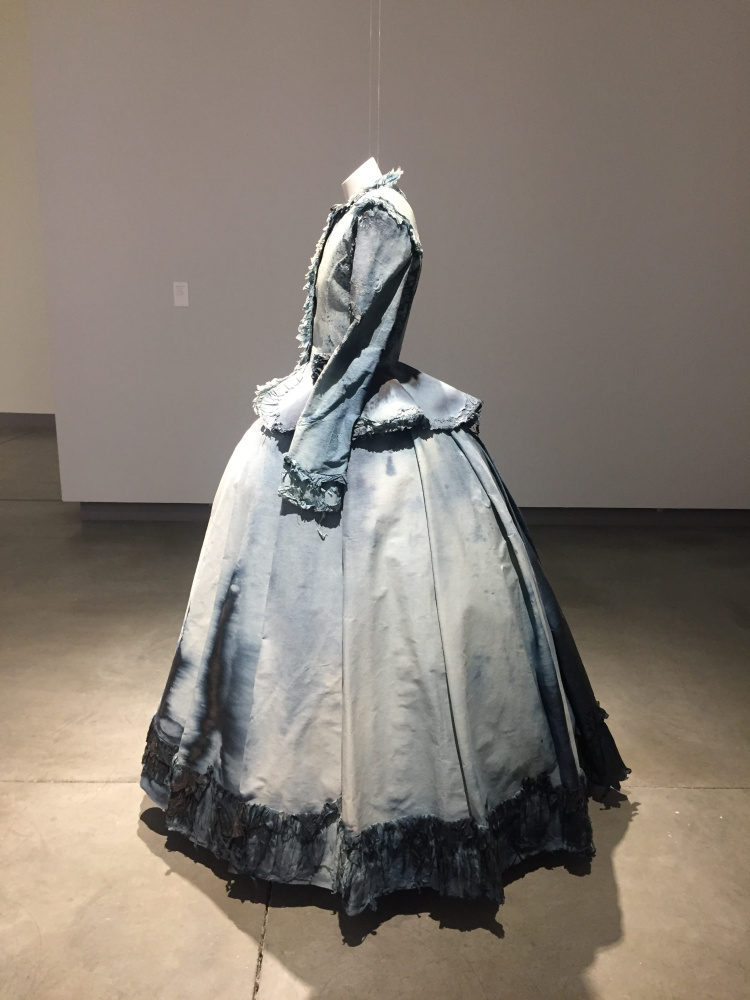

The most comprehensive and satisfying work in “Anguish” is Martha McDonald’s “The Weeping Dress,” which we see as a handmade crepe paper dress and a video of McDonald’s performance made while wearing the dress. Following Victorian mourning rituals, the crepe paper dress was dyed black. Crepe is not colorfast, so the dye would make the wearer’s skin turn black. In the video, McDonald sings under an artificial drizzle (to speed up the dye-loss process) where she stands in expanding inky pools while the dress transforms from black to faded blue – the state of the perfectly preserved and sculpturally presented dress across the room from the video. McDonald’s work delivers a feel for the first year of the Victorian mourning process; certainly, a dye-stained widow is going to be far less likely to engage in, say, sexual relations, and this pushes the sense of personal anguish into the publicly-enforced arena of women’s culture.

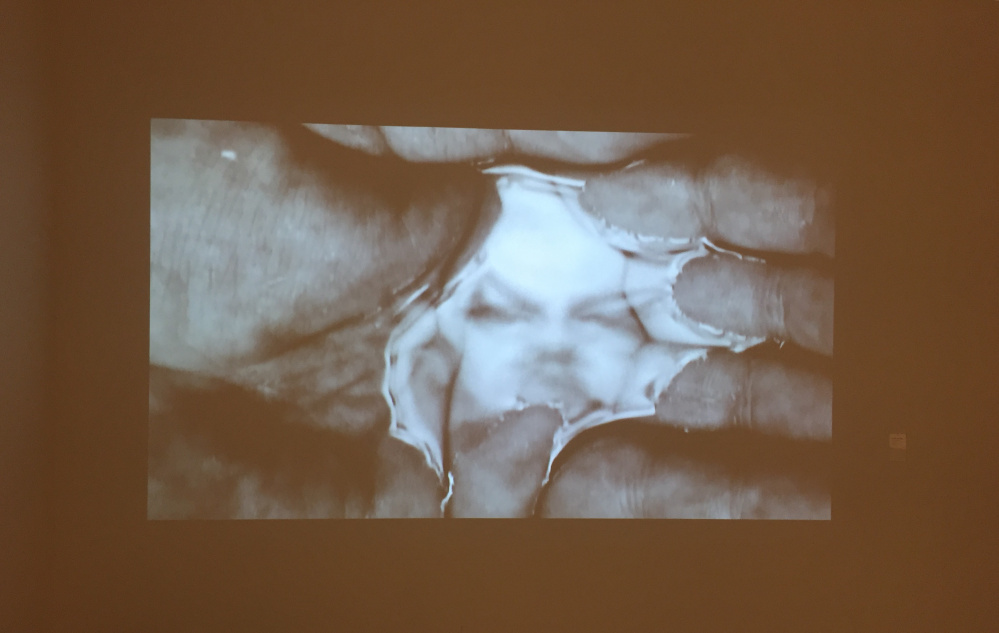

However, “Anguish” is hardly limited to a female perspective (my responses all came to me as a straight, white male), and it is this expansive role of gender perspective that truly opens up the exhibition’s potential. Oscar Munoz’s “Line of Destiny,” for example, is a short video of the artist’s face reflected in his handful of water. The video ends as the water trickles out between his fingers and his face fades away. Reflection, he hints, is a matter of perspective and ever-fleeing time. It’s part memento mori and part question about the male gaze: When it does fade, how can a man see himself? And how will he be remembered, if at all? This is a conundrum of death, and it’s a haunting thought.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.