‘Some stories hook into the imagination’

Elizabeth Searle has long worked at the intersection of spectacle and news.

She wrote the libretto for “Tonya & Nancy: The Rock Opera,” a story of Olympic skating and scandal that has played in several cities to critical acclaim. In her 2011 novel, “Girl Held in Home,” she harnessed the fear and paranoia left in the wake of 9/11, to devise a tart domestic thriller.

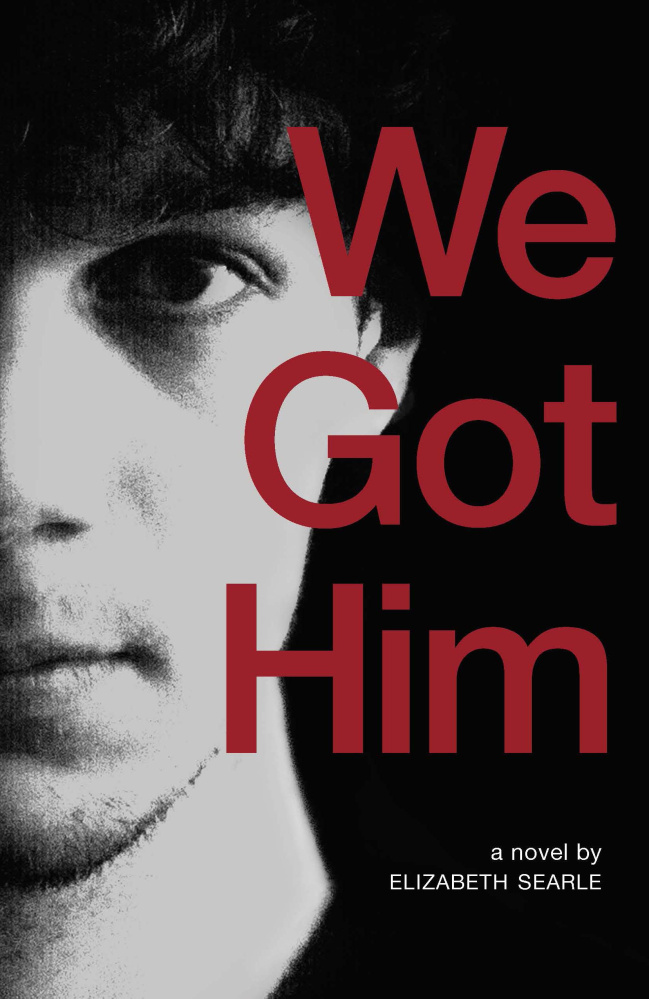

For her new novel, “We Got Him,” Searle homes in on the manhunt that followed the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, around which she weaves the tale of a troubled family. A versatile, darkly comic writer, Searle brings a pulsing, kinetic quality to her work.

“I come from a very political family,” she says. “My dad was a news junkie and a political junkie. He always used to say, ‘The news is the greatest show on earth.’ He couldn’t understand why anyone wouldn’t constantly be watching the news.”

Searle, who teaches fiction and scriptwriting at the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast MFA Program, spoke recently from her Boston-area home about fiction and folklore, dialogue and divining rods. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You’ve made use of several major news events in your work. Talk about the role of public imagination and the preconceptions that readers bring to works based on familiar events.

A: We’re such a fragmented society. I grew up moving all the time, and these news events were the things we experienced together. You know, they’re our shared narrative. Some stories hook into the imagination and become like folklore. It feels like charged material. I always tell my students that it’s like holding a divining rod; you want to go where it’s charged.

Q: What specifically drew you to the story of the marathon bombing?

A: People hook into different things. When the first pictures emerged of the younger brother, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, with the white cap on, carrying a backpack, they were so blurry. They could almost have been anyone.

Q: Exactly. He looked like any kid in the neighborhood.

A: Then, as the night went on, they finally got to the defining picture, which was, of course, his student ID. And I thought, “Oh my God, I have a teenage son!” To me, that was the most horrifying aspect of it: This young person – how does this happen? But definitely the image of that face, and how it got clearer as the night went on, really struck me. I used that in my plot.

I already had this couple that I’d been writing about for years in short stories. I had them going through a sort of marathon, in a sense, trying to have a baby. And when I saw Tsarnaev’s face, and I was so obsessed with it, it suddenly hit me: What if their stepson was somehow connected to this terrible happening?

Q: It sounds like you had the makings of the story – the characters, then the news event, and the growing obsession.

A: Yes, it meshed in a lot of ways. I fixed on the moments of that manhunt night that just spoke to me: The image of tanks rolling through Watertown was like the movie “Blade Runner.” Also my son and my husband were here in the house, under lockdown. I was on a bus, coming home from New York City, as this stuff was unfolding. It was horrible not being there.

I wanted to write a novel that took place on a birth night, structured around the stages of labor. But until 2013, there wasn’t an engine to drive it. The novel takes place on the manhunt night, which is also the birth night in my story, and this little family is caught up in it, hour by hour.

Q: Tell me more about the couple in your novel.

A: I had been developing them, in a sense, for a long time. They were just this couple who I wrote about three or four times – about them wanting to have a baby. Of course, you have to write what you know. I’ve been married for 30-some years, so that’s what I know – a long-time marriage. I thought it would be interesting to throw in the element of the husband having a nearly grown son, so it’s a blended family. I think all of that is interesting and hard.

I like to throw a loose cannon into anything I write – some character who’s the wild card. Definitely the stepson in this book is the wild card. He really wants attention, he resents the new baby that’s coming, the second family that his father is raising.

Q: Obviously you’re drawn to real-life events as backdrops for your stories. Do you have any interest in writing nonfiction?

A: You know, I’m always open to anything. I’ve done a novel, a novella, short stories, different kinds of scripts. To me, it’s all writing. I write wholeheartedly in whatever format. Nonfiction is almost the only thing that I haven’t done.

Q: You’ve written in so many genres. Does that reflect a restlessness, an adventurousness, or something else?

A: Both of those. I love different kinds of writing. The first writing I did as a kid was scripts. My sister and I acted out a soap opera. We put it on a cassette tape, and we thought we were broadcasting it on walkie talkies.

Q: I’m wondering how these different genres influence each other. For example, has scriptwriting made you better at writing dialogue in novels?

A: Yes, I think so. My earlier fiction is fairly descriptive and dense. But when I first started writing scripts, I felt like I had weights cut off my hands. You can just go so fast, writing dialogue and action. You learn to think in a more dramatic, visual way.

It’s a whole different mode. With scriptwriting, you have to rewrite on stage. You have to just see it, to see different versions of it. Rehearsals are a thrill. I love it, but it’s grueling. It’s not like with a novel, where you can sit with it for years and have different people read it. You have a lot more control with fiction.

Also with these news stories, you try to look for the right form for the particular story.

Q: At this stage, do you consider yourself primarily a novelist, a librettist, a scriptwriter?

A: Well, I think I’m primarily a fiction writer, but I’m sort of split. In recent years, the scriptwriting has been very consuming because of “Tonya & Nancy,” but I still have the longest loyalty to fiction. I’d love to just keep doing both and to switch off. I like to have lots of irons in the fire.

One of the things that makes writing so fascinating is that you can never get all the way there. In some professions, you can learn all there is to know, and you’re doing it as well as you can. But with writing, there are always better things to aspire to.

Q: And there’s always something that you’re reading that makes you think, “If I could only do that …”

A: Yes, and you get inspired by that. I like things that are kind of edgy. And I feel that it’s part of a writer’s job, in the higher sense of the word, to make trouble – to point to things that people are afraid to talk about.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.