“The Pilgrim’s Progress” is Able Baker Contemporary’s quirky but ostensibly unironic foray into spiritual art. It’s a fascinating show with a bizarrely functional aesthetic. If you could call it “beauty,” it would be the type the surrealist Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore-Lucien Ducasse) famously described as “beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella.”

The goal of “Pilgrim’s Progress” appears to be a broad view of regional religious and spiritual art. It reaches from mystical modernists like Richard Brown Lethem to street-style, posterized Christian “icons” to Shaker “gift drawings.” But the title even tilts toward a false start. It refers to the 1648 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan: “The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come; Delivered under the Similitude of a Dream.” It has long been a particularly popular Christian text, but Bunyan was a Christian on the edge: He spent many years in prison for his semiheretical acts and texts. Bunyan worked on “Pilgrim’s Progress” while in prison for his religious activities.

Exhibition titles set the initial context, and this one casts an iconoclastic shadow in the name of sincerity over organized religion. The show’s stated goal, after all, is to exhibit “artwork made by people for whom a sincere approach to religion and/or spirituality is integrated into both life and creative practice. Devotion and spiritual belief take forms as diverse as the people who hold these beliefs, but the number of contemporary visual artists who prioritize spiritual life is relatively small.”

First of all, that “relatively small” number is simply not true. Maybe it’s true in the hippest nooks of Brooklyn, but the contemporary art world is broad and that’s a blinkered view.

The inclusion of “historical reproductions” of Shaker “gift drawings” – screenprinted copies made around 1970 of originals from the 1800s – is probably the most fascinating and the most troubling aspect of “Pilgrim’s Progress.” The basic expectation of art galleries, after all, is that they present real works of art. (Museum expectations may include complete historical narratives, but the public expects object integrity from galleries rather than stand-in illustrations.)

The curatorial concerns here may be mollified by considering the images are courtesy of the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Community in New Gloucester. There are only about 200 extant Shaker “gift drawings” – a truly American manifestation of art in which inspired images were made by Shakers, common parlance for members of the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Coming.

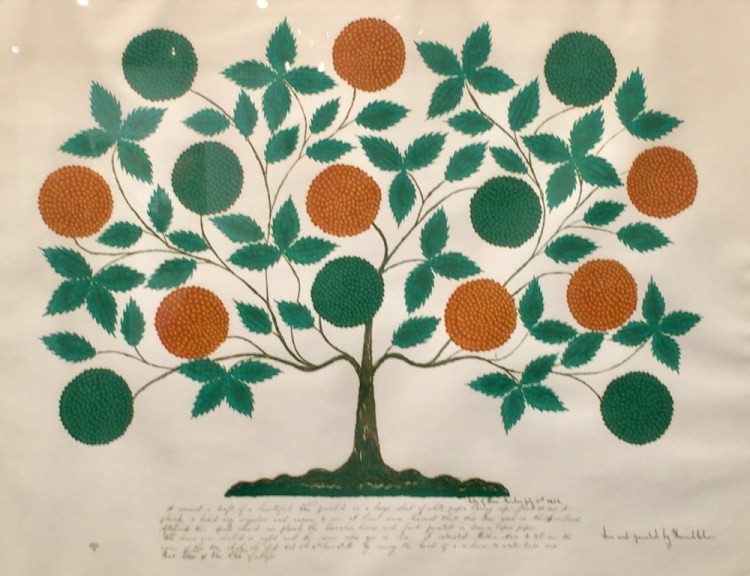

The unspoken context for the “sincere approach” of “Pilgrim’s Progress” is individual vision. This actually works for the “gift drawings,” since, uncharacteristically for the community-minded Shakers, the drawings were individual visions put on paper: an oddly fruited tree, visions of community that look like chorus maps of seraphim rendered in a primitive but pristine style.

These images include descriptive dream texts in beautifully compact script. The style of the drawings hearkens to colonial era English and American decorative stenciling, but it also recalls William Blake and illuminated manuscripts. (More common were the thousands of inspired hymns that came to Shakers; but they would be sung by the group rather than seen by the individual.) But this puts the Shaker community in a weird place. We aren’t seeing works coming from churches, temples or mosques, after all.

Sure, Jesus shows up, but even when his presence isn’t soaked in the ironic trading of valentines with Satan, he’s more the product of a visionary sensibility like Michael Waterman’s, whose “Carrying the Cross” is comfortably straightforward and welcomingly genuine.

Even if Waterman’s figure is a re-enactor (there is a contemporary city behind the traditionally painted figure), it is a heartfelt image of a heartfelt scene.

Waterman’s “Angeles Domini” combines the visionary with the institutional in a clearly devotional manner: A man has a church, literally, growing out of the top of his head.

Lethem’s visionary scenes pop with authenticity in this context, but they are the exceptions.

Each sets up its own system, although, ultimately (and I imagine, unintentionally, since Lethem is a Quaker) they can work well as Christian-based mystical meditation objects.

“Horses of Plenty” has a cross at its center. “Prairie Dog” circles in on its ground dweller as a circle over a horizon-lined landscape. And “Touch Stones” follows a triangle to make a trinity of simple objects, including a cross and a holy-ghostish feather. Whatever your take on his work, however, Lethem is strong in this context.

There is also strong work that simply feels out of sorts when presented as primarily spiritualized.

Haley Josephs’ “Eve” is more art historical than biblical. A 1519 Durer print shows a pair of thoroughly secular peasants at the market. And Elizabeth Jabar’s images are strong and psychologically complex, but they are fundamentally humanistic. Her pair of silhouetted profiles deliver racialized images with a basic nod to community and added multiplicities of forms (faces, fires, ladders, tents), but the sense is heritage, not metaphysics.

Elizabeth Jabar, “The Cloud of Unknowing,” screenprint and woodcut on Japanese paper with beeswax on panel.

Jon Blatchford’s acrylic over laser print scenes are similarly engaging as artworks, but they fail to connect to any sense of higher power, except possibly in a Shaker-like salt-of-the-earth sense along the lines of, say, Jean-François Millet’s French peasant labor scenes, such as his 1850 “Sower.”

Blatchford’s past work has tended toward landscapes similar to his apple tree scene, only without the people. And this type of living landscape reminds us of the fundamental spiritual underpinnings of the traditional Maine landscape.

Winslow Homer and Frederic Church began a path of painting in Maine that aligned with the transcendentalism of Emerson and Thoreau.

To be sure, there is a spiritual clutch to the nature worship broadly evident in ambitious Maine plein air painting.

So, on a basic level, the idea of serious spirituality aligns the works in “Pilgrim’s Progress” with traditional regional sensibilities, but the show feels like an encyclopedic attempt that fell short.

The Shaker works, to be sure, are fascinating, but without appropriate institutional peers, they feel isolated, like outsiders. And in religious terms, that is an uncomfortable perspective.

Lautréamont’s awkward notion of beauty is fitting to “Pilgrim’s Progress” because it revels in the uncanny aesthetic of disjointed elements under bright, well-focused lights. And this is true of seeing spiritual (or “mystical” or “religious” – all these terms are, to a certain extent, insufficient and misleading) work in an art gallery, curated with a Frankensteinian combination of commercial art gallery, museum and contemporary kunsthalle logic.

In a museum, if the goal were didactic or historical, the Shaker reproductions could work, but in a gallery alongside works by so many contemporary artists, it’s too much of what we might find on a dissecting table when we expect something a little more alive.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.