All of Portland seemed to be in a bad mood that Sunday afternoon not too long ago. The sky was spitting rain in intermittent bursts, frustrating both the people who had gone through the trouble to bring an umbrella and the ones who hadn’t. Longfellow Square had become a knot of traffic; drivers honked at jaywalkers, who cursed back, as I rounded the corner on my way to St. Luke’s Cathedral.

I opened the church door. Inside, it was silent.

Had I gotten the time wrong? I was new to Portland and I’d only been to St. Luke’s, the seat of the Episcopal Diocese of Maine, once before – and that was for the busy, colorful morning service. I felt a pang of dismay as I hovered on the threshold, deciding whether to investigate further or just go home. Through the open door, I could smell the distinct fragrance that seems to emanate from every old church: incense, candles, flowers. I stepped inside.

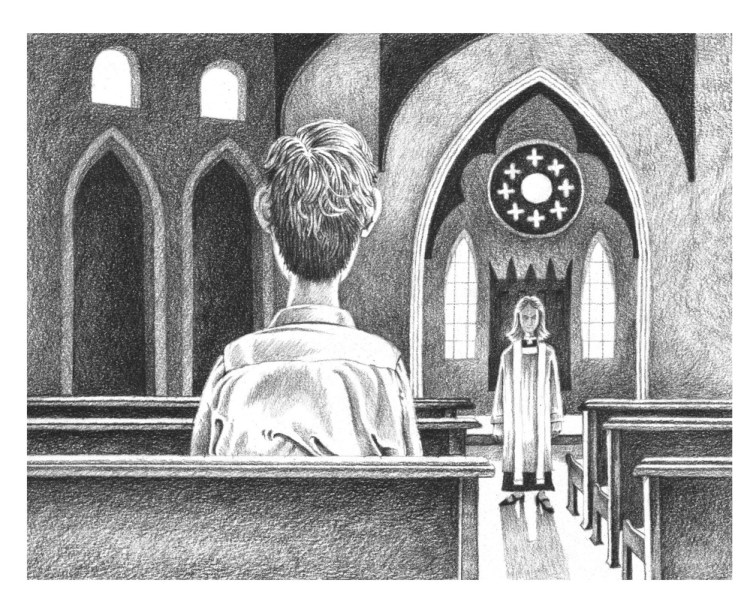

The wide, empty nave was dark except for the light coming in through the stained-glass windows. My footsteps had never sounded louder as I walked toward the little octagonal chapel at the back, where the Rev. Anne Fowler sat alone by the altar.

“Oh,” she said. “I guess it’ll just be us tonight.”

I was the only one who’d shown up for the 5:15 service.

I would’ve understood if she’d apologized and said there weren’t enough people to justify holding the service. But instead, Anne said, “We’ll wait a few more minutes before we get started,” and then went to put on her vestments.

I took a seat and looked up into the chapel’s spire. Every once in a while, some muffled fragment of a sound would surface briefly – a faint siren, rain on the roof – before dissolving. Candlelight brought a warm glow to the chapel’s wood-paneled walls, which fold into a partial dome over the altar. If you haven’t been to an evening event there, just imagine being cradled in a conch shell under a dark sea.

In those minutes, my understanding of the word “sanctuary” deepened.

I’d been to many small services before, like the nightly Mass at the Catholic college I went to, but I’d never been the only congregant. I wasn’t sure how it would work, but Anne was.

“I’ll start with these prayers, as usual,” she said, opening the program. “Would you like to do the readings?”

I told her I would, and we began. The service started just like any other, except that Anne’s voice was quieter than it would have been otherwise. Many of the prayers are fixed in the liturgy, so the words don’t change from week to week, but they sounded different this time. They weren’t just being recited into the ether. They were being spoken to me. They were being offered for me.

Such a poor turnout for an evening service isn’t surprising given the national trends. Episcopal churches, like those of other mainline Protestant denominations, are far emptier than they used to be. The Episcopal Church in the United States says average Sunday worship attendance at its churches declined 26 percent between 2005 and 2015. The Diocese of Maine says it lost nearly 17 percent of its baptized members in that decade, although some congregations in southern Maine are growing.

But Anne says the evening we met was the first time she had ever celebrated the 5:15 service with only one person.

“Usually there are somewhere between 10 and 20, and there is a core group that is pretty regular,” she told me later.

There have been times – just a few in her 30 or so years as a full-time minister – when no one came to one of her services, though.

The evening I showed up alone, the readings were both beautiful and challenging, as they often are. The first turned out to be from one of my favorite parts of the Bible: the book of Ecclesiastes. It’s a musing on the ephemeral cycle of life and contains some of the more recognizable verses in Scripture. (Its chapter about everything having its own season provides the text for Pete Seeger’s “Turn! Turn! Turn!”)

But this was one of the book’s darker passages, focusing on the futility of life on Earth. The walls echoed my own voice back to me as I stood in the center of the chapel, reading:

“What do mortals get from all the toil and strain with which they toil under the sun? For all their days are full of pain, and their work is a vexation; even at night their minds do not rest.”

I was tired.

“Church is supposed to make me feel better about my life, not worse,” I thought.

The Gospel was difficult, too: one of Jesus’ least comforting parables, in which a successful farmer stores his extra crops in barns only to incur God’s wrath for hoarding material wealth.

“You fool!” God says. “This very night your life is being demanded of you.” Harsh.

Normally the priest gives a sermon after the Gospel reading, but Anne sat down next to me. She didn’t preach. She wanted to know more about me, and asked what brought me to this church on this night.

I told her I was feeling adrift. I’d recently moved across the continent and, as much as I was loving Portland, hadn’t had time to adjust or relax. My life was changing rapidly, and it seemed like the world was too. When I feel ungrounded, I gravitate to the firmest ground I know, which is the church.

She asked how the readings made me feel.

“Confused,” I said. “And a little afraid.”

She nodded.

“These are some tough ones,” she said. “This language of fear and uncertainty is troubling, especially when it comes from the mouth of Jesus.

“And yet,” she went on, “he is speaking. He is there. He’s showing us a path so that when things do go wrong, we know where to go.”

As we talked, I thought about the timeliness of this little scene. In an age when many Americans have abandoned the institutions they once turned to for solace and truth, there we were, a priest and a journalist huddled together in an empty church. With the light fading and our voices low, it felt almost subversive, as if even kindness were a political act.

After we had shared communion and taken some time for silent prayer, she concluded the service and sent me on my way with the traditional blessing: “Go in peace to love and serve the Lord.”

“Thanks be to God,” I responded, more sincerely than usual.

She started putting out the candles as I walked out into the night.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.