Lennart Nilsson, a Swedish photographer who unveiled unborn life in electrifying images that were splashed across Life magazine, filled hours of acclaimed documentary films and decades later still brim with scientific, artistic and moral significance, died Jan. 28 at a nursing home in Stockholm. He was 94.

His stepdaughter, Anne Fjellstrom, confirmed his death but did not cite a specific cause.

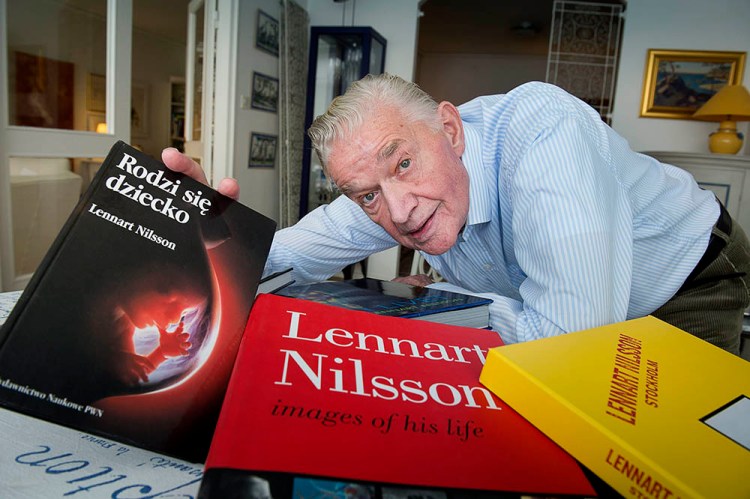

Latest edition of another of Lennart Nilsson’s classic works, originally published almost 40 years ago.

Nilsson was celebrated around the globe as a photographer of nearly singular genius. Drawing upon a primal sense of curiosity, he harnessed cutting-edge technology to capture on film such drama as human conception and the infection of a cell by the AIDS virus.

He was best known for his images of embryos and fetuses, as embryos become known about eight weeks after a sperm fertilizes an egg. Life magazine sparked a sensation when it featured his work in the 1965 story “Drama of Life Before Birth.” Eight million copies of the edition – with a cover image of an 18-week-old fetus cocooned in the amniotic sac, immediately recognizable as an incipient person – were sold.

Inside the magazine were portraits of the most ethereal quality, depicting beings never before seen by most eyes, and yet intimately familiar. At 6 1/2 weeks of gestation, an embryo displayed clearly visible hands. By the 8-week mark, a viewer gazing upon Nilsson’s photography could perform that cherished rite of delivery rooms and count 10 tiny toes. At 18 weeks, he captured a fetus sucking its thumb.

Nilsson used custom-designed equipment described by Life as “a specially built super wide-angle lens and a tiny flash beam at the end of a surgical scope.” But his photographs elicited amazement not at human technological achievement, but rather at the very fact – some said miracle – of human existence. “This is like the first look at the back side of the moon,” a Swedish gynecologist remarked upon seeing the images, according to Life.

Nilsson’s embryonic and in utero photography later appeared in “A Child Is Born,” a best-selling volume translated into an array of languages and reprinted in numerous editions over the years. On television, it was featured in documentaries including “The Miracle of Life” (1983) and “Odyssey of Life” (1996), both of which aired on the PBS program “NOVA,” garnering Emmy and Peabody awards.

In the 1970s, his photos were sent into space aboard the Voyager space probes – a calling card from mankind for any being that might happen upon it.

On Earth, Nilsson’s images held profound meaning for abortion rights opponents, who pointed to the photography to demonstrate how quickly cells combine and divide to form recognizable human life. Nilsson, whose subjects included dead embryos as well as live ones, did not venture into discussions of when life begins.

“If you are religious, you may believe that life starts 24 hours after fertilization,” he remarked. “Some scientists think it’s when the heart starts beating, 16 to 18 days after fertilization. It depends on yourself. I’m just a journalist telling you things. It’s my mission in life.”

He once told the Sunday Times of London that it was his “dream” to make the “invisible visible.” In that pursuit, he photographed blood vessels, the interior of the heart and ventricles of the brain. “Hairs of the head are seen as a grove of trees amid mossy stones; glands of the stomach as volcanic terrain; mucosal folds within the Fallopian tube as beautiful silken veils; calcium crystals of the inner ear . . . as monumental boulders, like some moonlit primitive Stonehenge,” Irving Geis, a biological artist, wrote in a New York Times book review of “Behold Man: A Photographic Journey of Discovery Inside the Body,” a collaboration by Nilsson and Jan Lindberg.

Lars Olof Lennart Nilsson was born in Strangnas, Sweden, on Aug. 24, 1922. He was 11 when he received his first camera. He once told the publication Technology Review that he “wanted to get close to everything, to see the miracle of life.” “I clearly recall the first pictures I took of laburnum,” his website quoted him as saying, referring to the tree with its distinctive hanging chains of golden flowers. “Even then, I remember thinking it would be exciting to see what laburnum looked like inside.”

At the start of his career, Nilsson worked as a freelance photographer, documenting a midwife in the Swedish highlands and Norwegian hunters on the trail of polar bears.

His marriage to Birgit Svensson ended in divorce. Their son, Kjell Nilsson, died in 2013. In 1989, he married Catharina Tjornedal. Besides his wife, survivors include two stepchildren, a sister and three grandchildren.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.