Federal authorities are closing the scallop fishery in the northern Gulf of Maine at 12:01 a.m. Thursday after a contentious three-week season that pitted the interests of part-time, small-boat fishermen from Maine against large, full-time scallop operators.

Fisheries regulators announced the closure Wednesday after small-boat fishermen – many of them Maine lobstermen operating 40- to 45-foot boats – met their annual quota of 70,000 pounds. The developments do not apply to the scallop fishery in state waters, which extend to 3 miles from shore.

This year’s federal harvest has been contentious because the large, full-time boats are believed to have caught more than 1 million pounds of scallops in the northern Gulf of Maine scallop fishing area, but owing to a quirk in federal rules the fishery could not be closed until the small vessels caught 70,000 pounds. This month’s storms and unseasonable weather had kept the small boats in port, delaying their ability to meet their annual quota and close the area to the larger vessels, who were permitted to continue harvesting large quantities of scallops under federal rules.

“We have a lot of fishermen who are very happy about it being closed,” said Ben Martens, executive director of the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, which represents many of the smaller boats. “We have boats that were fishing in bad weather they shouldn’t have been in, because they felt they had to meet the quota to close the fishery because they were concerned about the impact to the ecosystem and the sustainability of the larger resource.”

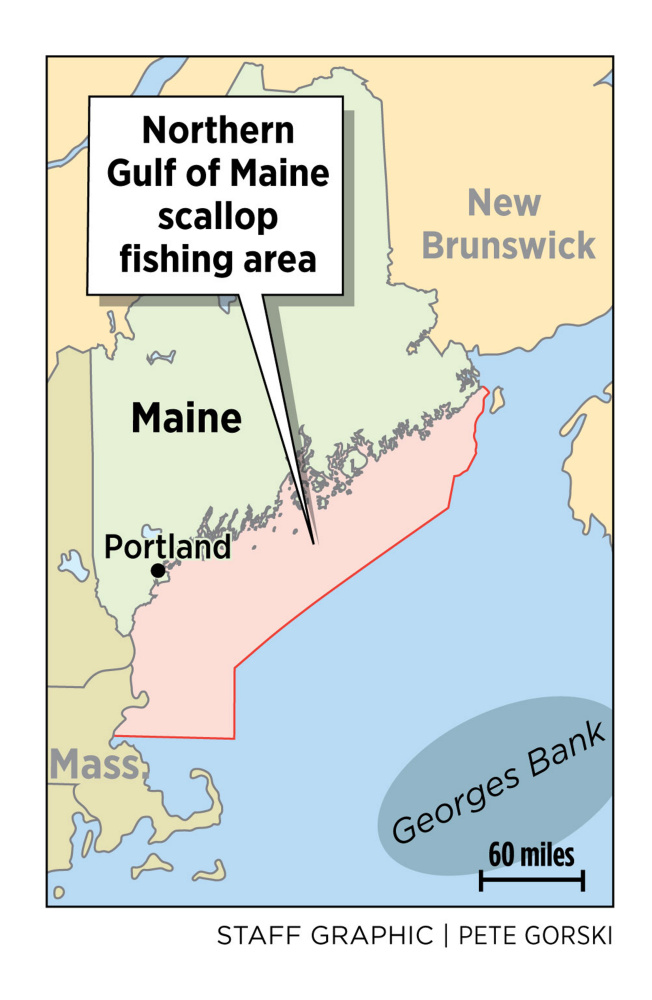

Small-boat fishermen have been protesting the regulatory situation for years, noting that the larger boats have no quota on how many scallops they can catch in the Northern Gulf of Maine scallop zone, a 40- to 50-mile-wide band of federal waters off the coasts of Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Instead, the larger boats operate with days-at-sea limits, and can use them wherever they wish, both inside and outside the northern gulf zone. The small-boat fleet’s advocates argue the arrangement jeopardizes the scallop stock in the area and with it the economic vitality of Maine’s fishing communities.

“This loophole needs to be closed once and for all,” said Togue Brawn, owner of Downeast Dayboat, a Portland scallop wholesaler and champion of the small-boat fishermen. “It is absolutely critical to the future of the Maine small-boat fleet. In Maine we solely depend on lobster, and we need diversity, to be able to go for other species.”

Last year, Maine’s scallop fishery – from both state and federal waters – was valued at about $7 million, while the lobster fishery exceeded $533 million.

Federal fisheries managers and full-time scallop fishermen say Brawn’s characterization is wrong, that the resource is thriving and that the part-timers in Maine are making a controversy where there isn’t one.

The scallop fleet in the Northeast tends to descend on one place with a high density of scallops on the bottom, dredge them hard and fast, and move on – a “pulse fishing” approach that was a disaster when employed against cod and other groundfish by factory-freezer trawlers in the 1970s and 1980s.

But the pulse approach actually works with scallops, which are thriving and well managed, said John Bullard, administrator of the northeastern regional office of the National Marine Fisheries Service in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

“People identify dense beds of scallops, the fleet moves in and fishes them very heavily, and then they’re closed and they move on,” Bullard said. Because they catch the scallops quickly, the dredges are dragged over a small area, reducing damage to the sea floor and collateral damage to other bottom life. “It’s a very efficient way to fish a lot of scallops, and it’s produced very good results over a long period of time.”

Drew Minkiewicz, a Washington, D.C., attorney for the Fisheries Survival Fund, a coalition of full-time scallopers, agrees. “That’s what we do with rotational access: We allocate troops there, we fish it hard, and when it goes away we close it and it comes back,” he said. “We stole it from agriculture, where they rotate crops or fields.”

“You can’t argue with success,” he says. “We are at abundances in the scallop fishery that were never seen before. This is a well-managed fishery.”

FISHING CONCENTRATED AT STELLWAGEN BANK

This season the action has been at Stellwagen Bank, which is off Massachusetts Bay and lies within the Northern Gulf of Maine scallop zone. The zone was created in 2008 as a concession to Maine’s part-time scallop fishermen who had not caught enough scallops in earlier years to earn a conventional federal license. They are allowed to fish within the zone using a small dredge with a day limit of 200 pounds. When they meet their annual quota – 70,000 pounds this year – the fishery in the area is closed.

That means both large and small vessels were fishing the same waters, and would continue to do so until the small boats met their quota. But bad weather in March presented an unusual problem: The small boats couldn’t get out while the big ones continued fishing, resulting in more scallops being taken than would otherwise have been the case.

Bullard and his colleagues at the fisheries service – part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – say the fleets probably took about 1 million pounds from Stellwagen Bank this year, about half of the total scallop stock thought to be there. “We don’t think the amount of scallops that will be taken out of Stellwagen threatens its sustainability,” Bullard said Wednesday.

That doesn’t mean there couldn’t have been a problem if the weather had kept the small boats in port for a longer period, Bullard said, but a proposed fix is on its way. Bullard said that Terry Stockwell, a Maine Department of Marine Resources employee who serves as vice chair of the New England Fisheries Management Council, is drafting a motion to put before the council that would put trip limits on the full-time vessels’ access to the zone. In a written statement to the Press Herald, Stockwell confirmed he was preparing a motion that would address “inconsistent management measures between the different scallop permit categories and the need for better science.”

That would be a relief to the small-boat fishermen, who note that if the northern Gulf of Maine scallops are depleted, the big, full-time scallopers can go elsewhere, while they aren’t allowed to fish outside the zone. “Small boats can thrive when they have a diverse fishery to move between, and we in Maine and New Hampshire need to increase and diversify the landings of our fleets of boats,” said Martens of the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association. “Small boats can’t leave and go to other areas, so the incentive is for them to have sustainable, long-term and growing fisheries there.

“We can’t have booms and busts with this resource.”

Togue estimated there was a core group of about a dozen small-boat Maine fishermen who regularly participated in the federal scallop fishery in the northern gulf. Minkiewicz’s association represents some 200 full-time scallopers from North Carolina to Maine, including Rockland-based O’Hara Co., which operates several large boats.

KING, PINGREE, COMMISSIONER PLEASED WITH CLOSURE

Maine Department of Marine Resources Commissioner Patrick Keliher said he was “very pleased” that federal authorities were closing the fishery. “The current situation was not envisioned 10 years ago when the (northern gulf scallop zone) was established, and we plan to address the management inconsistencies between permit categories through the New England Fisheries Management Council process.”

Members of Maine’s congressional delegation have been pressuring federal officials to address the situation. In a joint letter to Bullard on Friday, Sen. Angus King, an independent, and Rep. Chellie Pingree, a Democrat who represents Maine’s 1st District, expressed concern that overfishing might be taking place and requested further information on measures the fisheries agency was taking to protect the resource.

Both were pleased Wednesday that the fishery is being closed.

“I am glad NOAA has responded to our request for action,” Pingree said in a written statement. “This closure will not only allow the New England Fishery Management Council to consider changes to some of these loopholes, it will allow NOAA to accurately determine the amount of total catch that has been harvested this season.”

King said the closure “will at least result in a temporary respite to the problems caused by the flaws in the current management plan, but it also highlights the continued and critical need to develop a more vigorous strategy that meaningfully and fairly accounts for all harvests in the area and doesn’t pit fishermen against one another.”

Both said they would continue to follow the fishery management council’s deliberations to ensure the resource is properly managed.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.