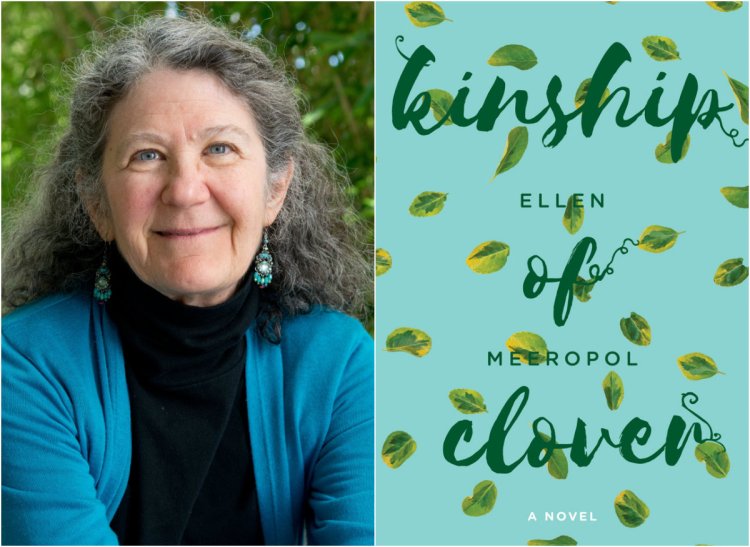

Ellen Meeropol’s new novel, “Kinship of Clover,” is heartbreaking and haunting, with a cast of finely drawn and deeply memorable characters.

There is Jeremy, a college sophomore and a botany major who is overwhelmed by the daily extinction of plants and who still suffers from the trauma of the deaths of two half siblings when he was boy. He sonorously recites strings of the Latin names of lost plants like a funeral dirge on his college radio show. “He savored how the Latin names balanced on his tongue, draped across his teeth, and fell from his lips. He didn’t speak their language, but he was fluent in its elegies,” writes Meerepol, who lives in Massachusetts and earned a master of fine arts from the Stonecoast program at the University of Southern Maine. In his darkness moments, Jeremy secretly suffers delusions of plant tendrils growing from his arms.

And there is Zoe, a 16-year-old girl who uses a wheelchair and believes everyone holds powerful contrasting elements within. “I am able-bodied and impaired, whole and broken,” she says at one point in her journey of first love.

Flo, Zoe’s grandmother, was a firebrand as a young radical during the 1960s. Her grip on memory is eroding steadily under the advance of Alzheimer’s. Yet she is still fighting injustice, while also dispensing heartfelt guidance during moments of lucidity.

All good stories turn on conflict, but there is a plethora of discord and tension in “Kinship of Clover.” At times, it almost overwhelms the story, requiring attentive reading so as not to get lost in the entangling threads of drama.

Jeremy and his twin brother, Tim, grew up in a commune with numerous children and parents – but few adults. The commune ultimately collapses following a midnight bonfire in the woods during a snowstorm, a festival of music, dancing and drinking. Amidst the exuberance, Jeremy and Tim’s younger half-sister and -brother wander away and die of exposure. Their father is arrested for negligence and is sent to prison. Growing up, Jeremy can’t escape memories of the event, while Tim does everything he can to suppress them.

Zoe’s life is likewise complicated, living in a three-unit house, she and her mother on one floor, grandmother Flo on another, and her father – divorced from her mother – on the third.

Flo continues to maintain weekly contact with a cohort of women who’ve known each other since they were young political agitators. Her friends grow increasingly concerned at Flo’s inability to remain connected to the here-and-now. Flo, in turn, grows evermore absorbed by a dark secret from her distant past that she has never shared with anyone.

When people at Jeremy’s college become alarmed by his bizarre behavior, a woman at campus health services encourages him to visit his brother in Brooklyn. Though deeply bonded by their childhood, they couldn’t be more different – at least on the surface.

While in Brooklyn, Jeremy becomes acquainted with a group of young eco-terrorists. His brief, cursory association is enough to attract the attention of the FBI when the group’s activities turn violent.

Tumult and trouble is everywhere, but those with the most to lose, when asked how they’re doing, repeatedly assert, “I’m fine.” What they are actually doing is the best they can under the circumstances.

Jeremy and Zoe go to visit her grandmother in the assisted living unit she’s forced to enter. At one point, Flo stresses that what distinguishes a person as a radical is “making the commitment and following through, no matter what the consequences.”

Jeremy asks if she really believes that: “Because the consequences can be huge.”

“What happened to you… (t)o make you ask about consequences”? Flo asks. Before he can answer, she drifts off again, leaving Jeremy to ponder the existential question on his own.

Flo seizes hold of a moment of clarity in a subsequent visit to finally answer his question: “Whatever action you take… make sure that when the smoke clears… you can live with what you did.”

Flo’s succinct and cogent answer is central to the lives of all major characters in the story. And Meeropol’s close crafting of their storylines proves in the end to be both moving and wise.

Frank O Smith is a Maine writer whose novel, “Dream Singer,” was named a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize and a Notable Book of the Year in literary fiction by “Shelf Unbound,” an international review magazine. Smith can be contacted at his website:

frankosmithstories.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.