Maine is awash in excellent photography at the moment, and nowhere more than at the Portland Museum of Art. The Judy Glickman Lauder collection is captivating, but it will be up for some months, so here we are looking to “The Thrill of the Chase,” highlights from the J. Paul Getty Museum Wagstaff Collection of Photographs, which is only open through April.

Samuel Wagstaff Jr. (1921-1987) will always have a spot in art history books because, through his jobs at the Wadsworth Atheneum and the Detroit Institute of Arts, he was the first American museum curator to show Pop Art or to curate an exhibition of what we now know as Minimalism. Wagstaff’s relationship to photography as an artistic practice is more complex. His own collection grew to well over 25,000 items and he was, among many other things, photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s lover in the early 1970s.

Featuring about 90 works, “The Thrill of the Chase” is huge. Arranged chronologically, it has more than enough heft to present itself as a historical show. Fortunately, the photographer with whom I went through the show suggested we start at the back. The early 19th-century works are more likely to read as artifacts or historical objects in context. Working in reverse, I was better able to see the photographic, rather than the historic, accomplishment of the photographers. The experience was not only more enjoyable, but it offered some unexpected insights.

That said, the show (appropriately) doesn’t end as strongly as its middle peaks, which accurately matches photography’s critical fortunes. “Thrill” reaches into the 1970s, but barely, which is to end on a crisis note. There are myriad versions of the rises and falls of photography: camera technology, color film, modernism, abstraction, print technologies, unmediated expression, the rise of glossies and commercial photography, and so on.

Whatever the cause of the crisis, however, we can now attribute a rather heroic role to Wagstaff. He collected obsessively – if he bought only one piece a day, it would have taken him more than 73 years – and he brought something else to the table, which becomes clearer with a close look through his eclectic collection.

This show includes early portraits, travel images, architecture, Native American subjects, civil war imagery, pictorialism, high modernism, abstraction and homoerotic subjects.

Featuring scores of black and white silver gelatin prints, “Thrill” is big enough that viewers will self-edit to the works that draw them in. I was snagged on a 1952 Robert Frank print of a woman in a ball dress, seen from behind. The effect of the dress on the woman was particularly fascinating: Her body became articulated like a bug, into thorax and abdomen.

While I am typically drawn to Man Ray’s work, I moved past him to see things rarer to me. Harold Edgerton’s 1930s multi-strobe image of a tennis swing, for example, challenged me because the approach is something of a shtick, but it is so beautiful that it drew me back.

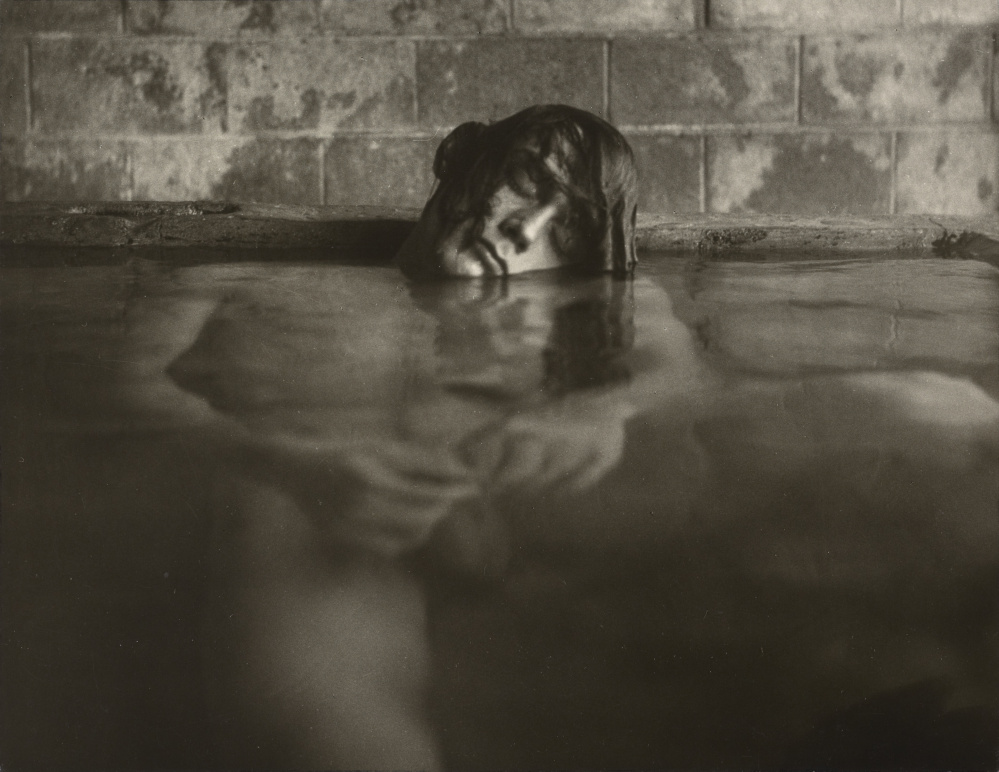

I found three spots in “Thrill” that I could hardly leave and that I returned to. The first included Edward Steichen’s bewitching 1924 portrait of Gloria Swanson under a black veil. The textures of the fiber and the draw of her eyes and lips continually interrupt each other. It’s a detailed image, but its success stems from a softer area above her right eye that serves as the blurry source of the image (like Freud’s navel of a dream). It is no document. It is not objective. And you cannot be either.

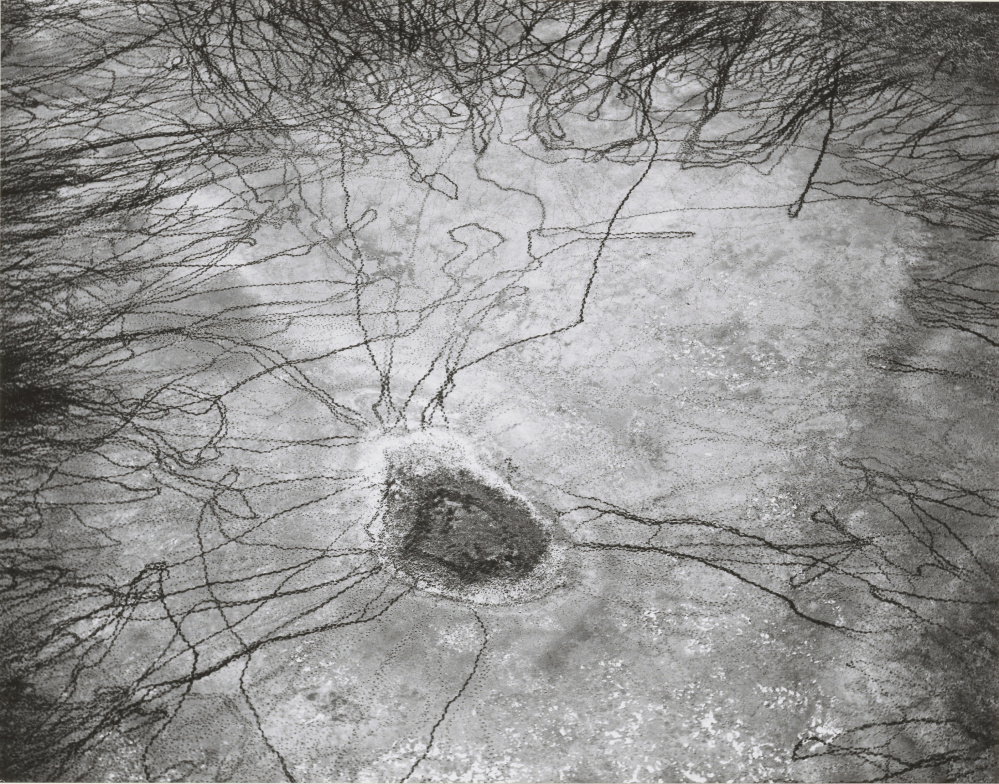

Beside the Steichen is a pair of Edward Weston’s Oceano sand dunes prints from 1936, hung one over the other. The lower image is somewhat clearer about what it describes, and it would likely be the strongest print in the show if it weren’t superseded by its mate. It is similar, but the immaterial dominates the top image with deliciously shadowed swaths of irrational black; it looks like sleep descending onto the waking desert.

My favorite spot in the show includes an Alfred Stieglitz silver gelatin print and a small 1896 platinum print of one of Frederick Evans’ images of attics. The Evans is soft, mohair beige and oddly bathed in white light. The organic internal structures of a stately building are dizzying and delightfully quirky.

Stieglitz’s “The Hand of Man” is a high-contrast dark masterpiece of a pictorial print. Under weighty silver clouds, light leaps off the train tracks snaking through an otherwise black foreground. The city leans in as rhythmic chunks and haughty towers, distant, crowded and removed. The train, solid and dutiful, churns its black smoke into the scene, but not as dirt. Instead, a white column of exhaust reaches out from behind it to create a photographic dialogue of light and texture.

The other spot that brought me back included a tiny and unexpectedly spatial period print of Native Americans dancing around a fire and Carl Moon’s 1907 portrait of a Navajo boy. The boy is unapologetically beautiful, enough to make us almost forget the tonal grandeur of Moon’s print – but not quite.

I could discuss any of a dozen other works that caught my eye, but there would be no increased sense of thematic coherence. Some of my favorites, such as Philippe Halsman’s 1948 “Dali Atomicus” would only add to the conceptual chaos. Halsman’s photo is hilariously entertaining: The hysterically wide-eyed surrealist painter jump-floats in the air amid soon-to-splash water and flying wet cats. It’s crazy. It’s fun. But it’s also a hell of a photograph.

Another that stood out was Lisette Model’s 1940-41 “Running Legs, Forty-second Street, New York,” an uncanny scene in which a motion-blurred pump-wearing foot opens our view to the clattery weight of so many feet in busy motion, oddly caught in a moment when all happen to be extended to the street.

What comes into view through “Thrill” is the artistry of the silver gelatin print (and its variants) and Wagstaff’s dedication to connoisseurship. These may sound like disparate ideas, but they relate directly. What people saw as images 100 or 150 years ago were monochrome prints: etchings, photos, drawings, engravings, litho illustrations and so on. Qualities of the print itself mattered, and people looked closely. For a serious photographer, making a silver gelatin print – dodging, burning, spotting, etc. – can take hours, and that means looking very closely.

Connoisseurship may be unfashionable, in part because people who purport to be art experts don’t understand connoisseurship and the nuanced distinctions between, say, gauging artistry, craft and the technical qualities of an object. To understand Wagstaff, we need to think in these terms: It is what he presses us to do – to look back and consider works on the terms of their artists, of their technologies, of their day.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.