The frame on a painting might act like the border between the art’s imagined world and the reality around it, but it also is a kind of flag that marks the start of the art experience for the viewer. The framing of art goes well beyond wooden rectangles and pedestals. Framing can include gallery walls, labels, lights, other works of art and so on.

Dowling Walsh is a gallery that generally relies on traditional framing. Even with contemporary art, like the razor-sharp edges of Cig Harvey’s exquisite photos, the framing is clear. So it was an intriguing surprise to see the works in “Construct,” a curated group show more tethered to conceptualism than tradition. Aaron T Stephan’s stacks of cinder blocks spiraled up into the air: the blocks themselves are curved, and it is this undermining of their utility that frames them as art. One of Stephanie Cardon’s works also uses cinder blocks, but she uses them to support (and frame) threads that create moiré interference patterns. Such patterns create a perceptual frame since they appear, shift and move with the position of the viewer.

The most interesting aspect of “Construct,” however, is the inclusion of paintings by Elizabeth Fox and prints by Fairfield Porter (1907-1975). While Porter’s paintings were often liquidy off the brush, they exude a dry coolness with an aloof remove. Porter wasn’t just a painterly artist but a leading cultural intellect, so it’s easy to assign this distance. However, the coolness in his works was an effect of the evenness with which he would treat his surface. Fox’s work uses a very even surface, but the effect feels quirkier since she uses it to clarify her heavily stylized approach. Her scenes are so flat, they are not even stage-like. In “Help in Wonderland,” a couple walks up a path that scissors back and forth up the canvas. The trees are flat. The closer ones are transparent, a quality Fox wittily echoes in the skirts of her cartoony women. It’s an increasingly tricky joke about depth, but it’s straight-faced humor, like Leslie Nielsen in paint.

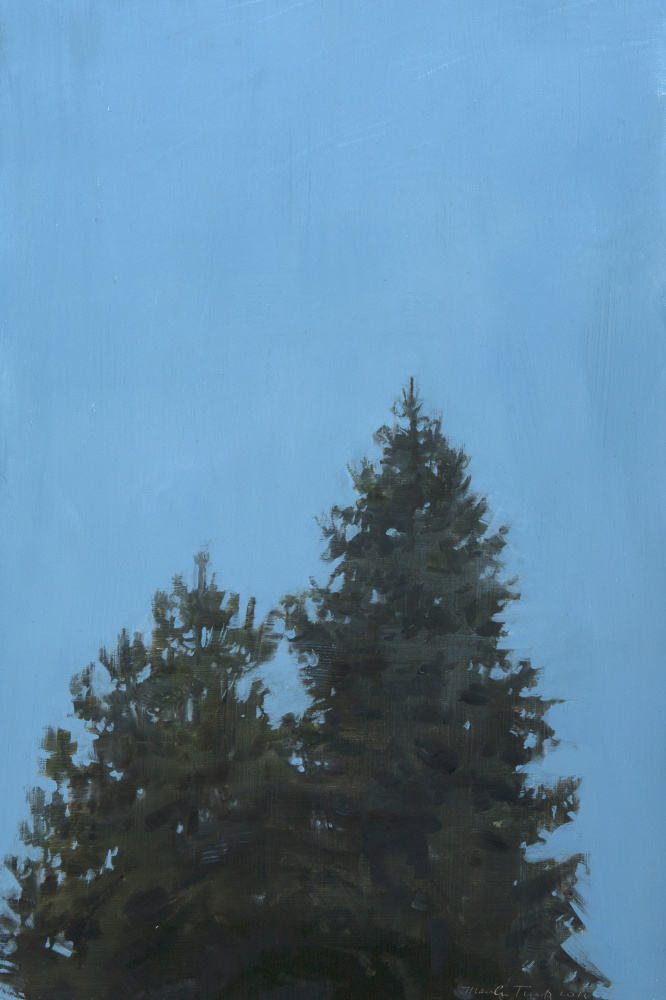

Fox’s surfaces are much like Marilyn Turtz’s, who was a featured artist at the gallery in May and whose works will continue to be on display. Turtz’s images are simplified landscapes free of any narrative quirk, but she shares a soft-polish surface quality and a limited, low-contrast chalky palette with Fox. Turtz’s work is very quiet, relaxed and unassuming, so it reveals itself slowly. This is unexpected because of the simplicity of the images. In “Evening Trees,” for example, we see nothing more than the upper tips of two pines against a flat blue sky. Because there isn’t much to recognize, we are quickly drawn into the quality of the paint. And since the work is only 12 inches by 8 inches, we are drawn in close to follow the tiny strokes. But it’s all there: Turtz can really handle a brush. To see the surface work, we need to be in reading range, which is undoubtedly the distance at which they were painted. Then, “Evening Trees” is a different painting. The simple scene becomes a gorgeous surface. The atmosphere swells like before a thunderstorm on a June afternoon. The unity of the trees divides into branches, and those into needled twigs, each with its own direction.

Trees are complicated things, and so to paint them, artists inevitably find a stylized and legible shorthand. Turtz does this but, within the larger unity of the tree, she maintains a quiet reserve of sophisticated effort. In other words, Turtz’s work doesn’t insist on a close look, but it rewards it greatly.

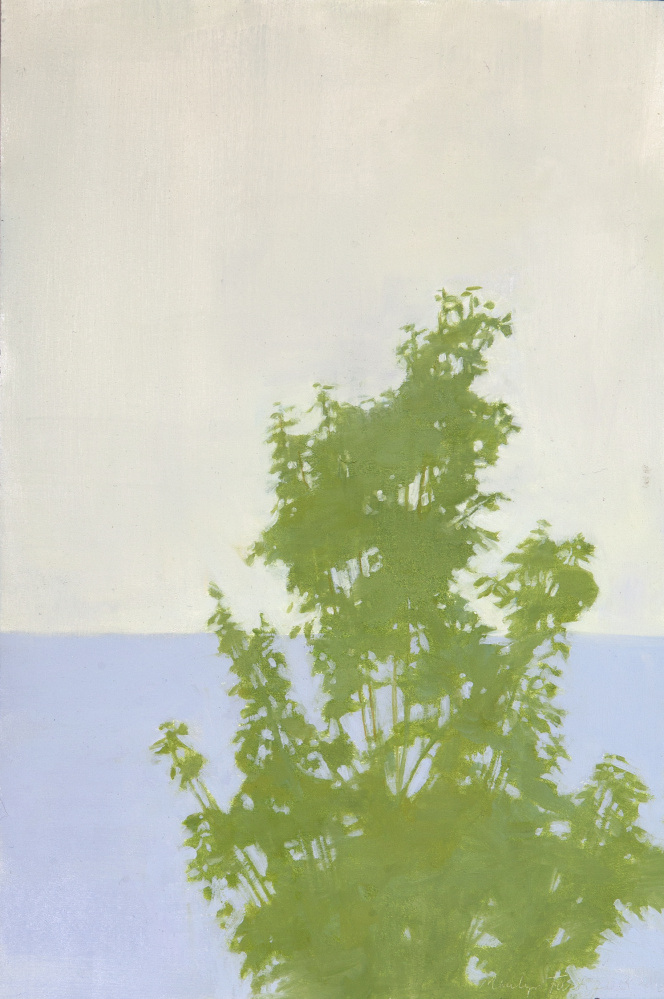

“Young Buck” is a singular tree in a flat, chalky olive green with a gray-white sky over a flat gray-blue body of water. It’s three simple colors with little contrast and even less saturation. But Turtz catches us on the motions of the branches moving up and down past the horizon line. The motions of the tree are literally the motions of the painting. And here again, the scale offers an intimacy that supremely matches the winsome rhythms of the brush.

While Turtz has a range of surface textures, palettes and landscape subjects, her strongest works share that semi-polished surface, the penchant for flatness, appetite for simplicity and her atmospheric virtuosity. She does have a few quirks too, however, such as a taste for images of a suburban neighborhood in which we see the back of a single car, poorly parked or disappearing, but always impersonal.

At 12 inches by 24 inches, “Longview from the Studio” is one of Turtz’s larger images. It is a scene from a hilltop looking past tall, scraggly pines toward what appears to be Penobscot Bay in winter. The river is snow white. There is no snow directly visible anywhere however and it is atmospheric perspective that pushes the background into the deep distance. The mystery remains unspoken and we may all read the same images somewhat differently.

While Turtz mixes in suburban scenes, a few cars, and a range of landscapes, she’s at her best with simple scenes peering past islands in the fog, like “Early Morning Distant Island,” or with horizonless treetops, such as the scraggly leafdropper in “Winter Trees” that pushes forward it evergreen partner.

Oddly enough, Turtz’s thirst for atmosphere makes her diminutive panels demand as much wall space as possible. This is a rare thing for paintings that pull the viewer in so close, but it’s apparent when you encounter her work at a distance. Her panels are even and hang flat against the wall, elegant and unfussy.

This kind of understated visual intelligence is not typically associated with traditional Maine painting, which, because of its plein air roots, is a sort of action painting: spontaneous, performative, high energy and stroke-driven. Glaze-smooth surface qualities have become more important over the past 25 years, but they are more the stuff of studios and process-driven contemporary art. And it’s not that stroke-driven traditional Maine painting is fading (it’s not: I see the likes of Colin Page, Connie Hayes and Philip Frye everywhere), but rather that the sophisticated surface sensibilities of contemporary painting are finding a growing audience.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.