Jason Yarmosky’s pictures are geared to first impression and impact. That is not to say they are superficial – hardly. But their content relies heavily on their effect on the viewer. Yarmosky’s paintings, drawings and video in “Somewhere,” at the University of Maine Museum of Art, generally depict his aged grandmother posing in outfits (e.g., a Wonder Woman bathing suit) and with accessories (e.g., a unicorn mask) that feel bizarre and out of place.

Ideally, the viewer doesn’t have Yarmosky’s program in hand as they enter the show. Analyzing one’s own first impression of what is meant to be a challenging show is a satisfying experience.

The first work I saw at the University of Maine Museum of Art was a 12-foot horizontal canvas of an old woman in a bathing suit standing before what looks like a drawing of a snowy field. The figure is rendered in a photorealistic style – Yarmosky revels in his model’s wrinkles – while the background is handled beautifully, with a much lighter and brushier touch.

“Wintered Fields” is an alarming image. The bathing suit doesn’t seem appropriate, particularly because of the superhero reference. If you see the scene as a literal snowy field, well, then the dangerous cold is obvious. If you see the mostly bare canvas as a theatrical setting, then you might immediately wonder if someone is taking advantage of the subject. Our standards for response are practically hardwired: respect and concern for someone whose agency appears compromised.

Balancing his content between the ethics of the artist and the morality of the viewer is, however slowly revealed, the ultimate act of Yarmosky’s humility. The deck is stacked against him, at first: He was born in 1987, which makes him a millenial, and he is everywhere announced as a Brooklyn artist, the current apogee of international art-world branding. His ability with a brush is facile enough for any cynical eye to see it as slick. And now that he’s an international “thing” (much of his work appears here courtesy of Aeroplastics Contemporary of Brussels), we can assume he’s cashing in on the images of this woman.

But Yarmosky again and again makes it clear that this is his grandmother, whom he loves and who is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. He enjoins our awkward responses with his own. And, ultimately, his warmth is undeniable. (The exhibition copy is clear about the works’ connection to issues of aging, vulnerability and dementia, but what works of art convey and how interested parties explain them in order to sell them don’t always align.) Yarmosky’s video portrait is close and warm, and however confused it is, its sympathetic struggle to understand is undeniable. The artist includes drawings he made as a very little boy, a gesture easily shrugged off as narcissistic until we see he was making art for this woman nearly as soon as he could lift a crayon.

Yarmosky invites us to question him. If you come to side with him, you might feel a pang of guilt for doubting him. Don’t. Yarmosky intends to show the struggle to connect.

The painting “Somewhere” shows the protagonist walking through a theatrical dream curtain away from a smoky wisp of a tree to someplace off stage right. If you parse the logic, the image works: Her final act (as in theater, but life as well) has passed from the rational toward the end of the story, like dreamy sleep after a long day. She is dressed for bed in a nightgown and slippers, but she wears a unicorn mask – a leitmotif of the exhibition symbolic of donning a fantasy mode, moving beyond reality. Most disturbingly, Her arms reach down practically to her feet at the end of tiny legs, as though she has been imprecisely returned to the form of a child. (Yarmosky has used the title “Elder Kinder” in the past, with the second word conveying sweetness in English – but “kinder” means “child” in German, as in “kindergarten.”) “Somewhere” works both as a symbolic painting and as a nod to the irrationality of dementia.

In “Smile and Maybe Tomorrow,” the braless old woman wears her unicorn mask and makes a curtseying gesture. The bowed length of nightgown between her hands forms the smile of the painting’s title. Her mouth and that of the unicorn are quietly distorted to make this a subtle shift from personal intimacy to the memory of an image. It’s the making of a memory out of those discomfiting ingredients of humor: the unexpected and the uncomfortable. Gorgeously painted, it is a work of subtle brilliance.

Yarmosky’s drawings and the straight “Portrait of a Grandmother” that greet the viewer do more to show the artist’s range and abilities than to add to the content of the show, but their positive context helps. “Somewhere” is a small show, but it is powerful. And it raises an interesting challenge for the artist: Because this work is so hyper-focused on his grandmother, what will Yarmosky do after her? On one hand, it’s a grim question, but one of his strongest qualities is his unblinking positivity (although with his humanistic sympathy for the irrational, he is no philosophical positivist). Yarmosky may be difficult, but ultimately, he is hardly dark. So where can he go from here?

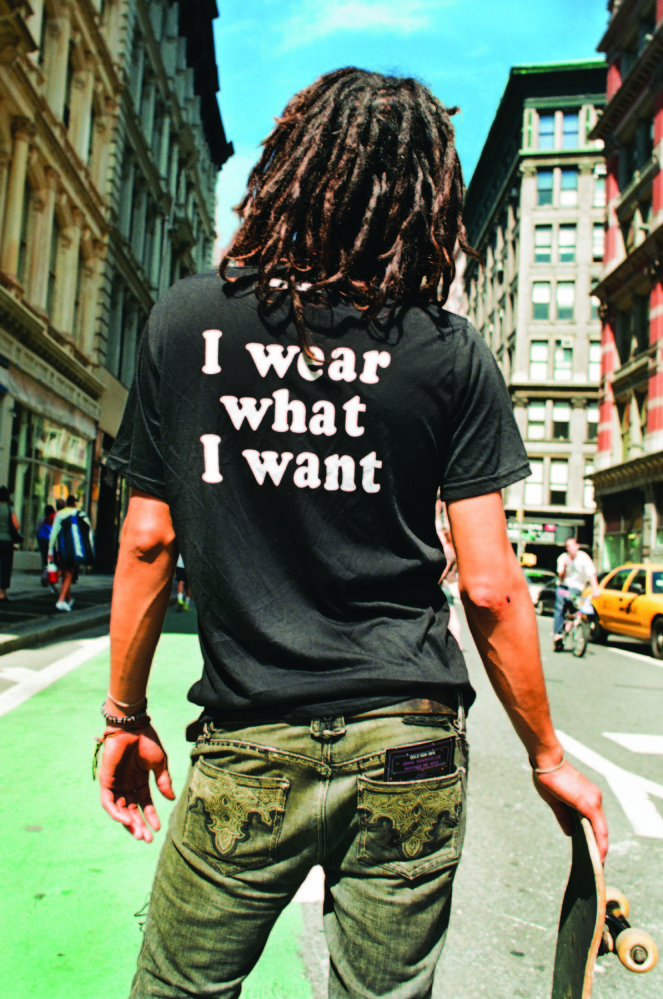

Susan Barnett’s “I Wear What I Want” is a large exhibition of about 100 posed-on-the-street photographs of the backs of people wearing communicative T-shirts. It’s an entertaining exhibition. Wearing their own captions, the subjects become billboards, but the writing feels more like graffiti messaging than capital-invested commercialism. Barnett’s process makes it easy to tick off row after row of the images, but this ellipses-ad-nauseum sense helps us see this with some societal depth. Indeed, one T-shirt features Andy Warhol, and we get the sense that the whole culture has taken a Warholian turn if pop art and what we see in museums is so easily able to come together, even down to Warhol’s proposition (now a meme) that, in the future, everyone will get their 15 minutes of fame. (Well, Andy, your snide gift is our present. Thanks?)

Rounding off the shows at the University of Maine Museum of Art is Lee Cummings’ “What Lies Beneath,” a monochrome installation of 300 white clay (kaolin) sculpted objects. It’s a silent punctuation, but it blends the process and the obsessiveness of Barnett’s and Yarmosky’s exhibitions, while offering a quiet and knowable context of craft and the life-affirming shapes of the natural world.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.