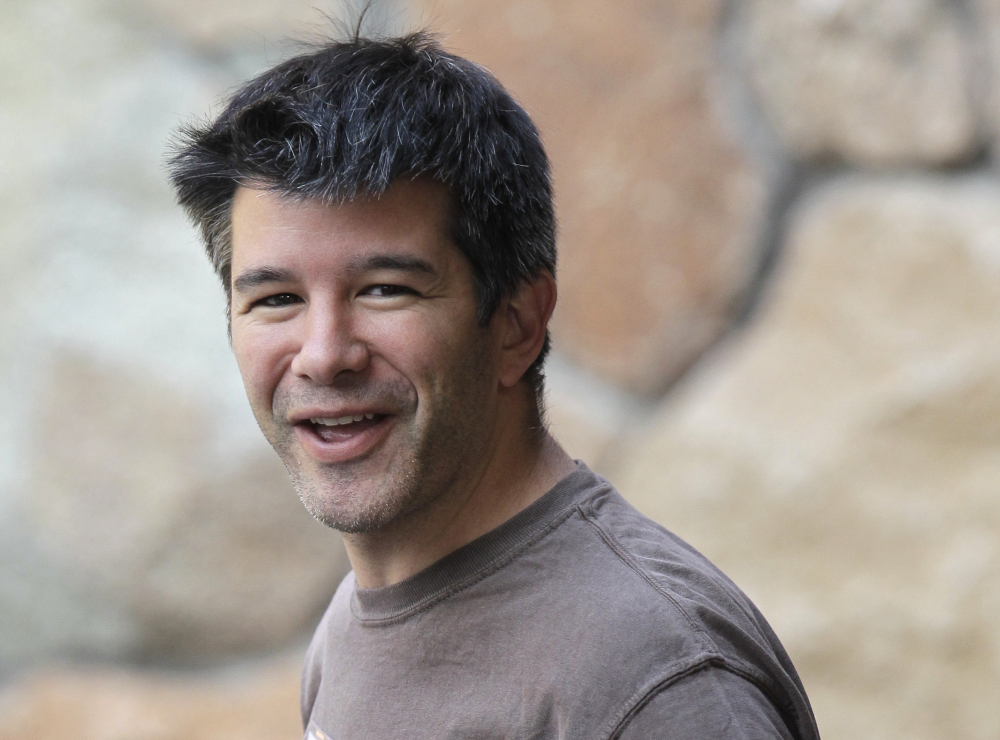

SAN FRANCISCO — The plot to oust Uber chief executive Travis Kalanick began almost the moment he announced last week that he was taking a temporary break from the celebrated technology company caught up in scandals.

The audacious effort to end Kalanick’s run atop one of Silicon Valley’s most successful startups was led by one of the company’s own board members, Bill Gurley, a major investor, according to two people familiar with the board’s thinking.

Even as Uber’s board of directors publicly appeared to support him last week, Gurley, a venture capitalist and early Kalanick backer, rounded up other Uber investors who also said that Kalanick simply could not return to the ride-hailing company he co-founded and grew from small startup to a company worth about $69 billion, according to the people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the confidential nature of the discussions. Gurley did not respond to a request for comment.

Uber had been rocked by an unrelenting parade of controversies, including allegations of widespread sexual harassment and executive departures that culminated in the board last Tuesday announcing 47 measures aimed at overhauling Uber’s workplace. That was when Kalanick, 40, said he would be taking an indefinite leave, in part to allow him to grieve for his mother, who had died just weeks earlier.

But it was clear almost from the start that Kalanick’s return to Uber was going to be contested, according to several people knowledgeable about what happened at Uber over the past week. From the moment his leave was announced, some people who knew the famously hard-charging Kalanick were skeptical that – based on how he had managed the company over eight years – he could change in the ways needed to allow him to return.

“Talking to other shareholders, most of us don’t see how Travis can ever come back to Uber as CEO,” one large Uber investor said the day after Kalanick began his leave, speaking on the condition of anonymity so he could discuss matters candidly. “A vacation doesn’t fix what he suffers from.”

Gurley’s renegade band of investors lacked the power to force Kalanick to step down. They needed to persuade Kalanick to make the move on his own. He and his allies retained enough voting power to reject the shareholders’ request.

So the investors began talking daily over email, in texts and meeting in person for coffee, according to one source. By the weekend, Gurley’s venture capital firm, Silicon Valley-based Benchmark, began to pass around a draft of a letter urging Kalanick to voluntarily step down.

The letter – signed by five major Uber shareholders, including Gurley’s Benchmark and other top names such as Menlo Ventures, Chris Sacca’s Lowercase Capital and mutual fund firm Fidelity Investments – demanded Kalanick’s resignation. The shareholders began circulating a short list of who could replace him.

The investors’ letter was sent to Uber’s full board of directors, including Kalanick, on Tuesday – one week after Kalanick had announced his leave from the company. No other member of the board, aside from Gurley, had signed it. Many at Uber, which declined to comment for this article, remained fiercely loyal to Kalanick. And even before Kalanick announced his leave, Gurley had unsuccessfully tried to persuade other board members to push him out, according to a person familiar with the board’s thinking.

After receiving the letter, Kalanick immediately called a member of Uber’s board to ask what he should do, a person knowledgeable about what transpired said. The board member advised Kalanick not to fight. The person described Kalanick as still grieving from his mother’s death and not in the right emotional place for a drawn-out fight – even one he could win. He needed to do what was best for the company.

The board member urged him to resign from his chief executive’s role, although he would remain on Uber’s board, according to one source, who would not name the board member Kalanick talked to.

That was what led to Kalanick sending an email just before midnight Tuesday in Silicon Valley to all 13,000 Uber employees that began, “I never thought I would be writing this.”

The email continued: “As you all know, I love Uber more than anything in the world, but at this difficult moment in my personal life, I have accepted a group of investors’ request to step aside, so that Uber can go back to building rather than be distracted with another fight. I will continue to serve on the board, and will be available in any and all ways to help Uber become everything we’ve dreamed it would be.”

And with that, Kalanick was out at Uber.

Less than two hours later, the man who initiated the push took to Twitter. Gurley did not gloat or acknowledge his role in Kalanick’s fate. Instead he wrote, “There will be many pages in the history books devoted to Kalanick – very few entrepreneurs have had such a lasting impact on the world.”

STRUGGLING TO REMAKE HIMSELF

One moment three months ago, when Kalanick was still firmly in charge at Uber, crystallized how Kalanick was struggling to remake himself and the corporate culture. Kalanick appeared before a group of Uber’s female engineers in Palo Alto, Calif., for what was supposed to be an informal question-and-answer session.

It was a Friday afternoon in early March, and he looked drained.

For the moment, Kalanick did not know the meeting was being recorded, and he appeared to talk with unusual candor, displaying little of the bravado he used from CNBC to Davos to describe how Uber was going to change the world.

Now, he was just trying to head off some of the damage from a recent series of scandals.

Kalanick admitted to the group he did not know exactly what to say about his company’s challenges. He had only jotted some ideas down on the SUV ride over. The last few weeks had been rough, the criticism intense. He had even stopped going on the internet.

He said he had met with Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg to discuss Facebook’s unconscious bias training. But Kalanick did not propose a plan to replicate that kind of training or any other concrete ideas. He only conveyed a vague notion that something needed to change.

“I’ve just been thinking a lot because of the cultural change that we’ve got to go through,” he said, in a little-noticed recording that Uber put on YouTube.

In Uber’s culture troubles, critics saw echoes of Kalanick’s own excesses. The board of directors investigation revealed a cut-throat workplace that often turned a blind eye to problems. Among the recommendations the board adopted were more management training and a rethinking of Uber’s 14 cultural values, items that Kalanick himself was instrumental in creating.

‘GROWING PAINS’

The idea for Uber was born in 2008, when Kalanick and tech entrepreneur Garrett Camp were attending a computer conference in Paris and tossing out ideas late one night. It is an origin story often shared by the two men. Camp noted how hard it was to get a taxi, especially in San Francisco, where Uber would eventually be based. He floated the idea of hiring some limos and some drivers and connecting them to an iPhone app that allowed for an on-demand taxi service. Kalanick loved it.

The duo brought different qualities to the company, Kalanick said in a 2011 interview on Jason Calacanis’s web show about startups.

“Uber is very classy, and it’s very efficient,” Kalanick said.

Camp brought the classiness, he said, and “I bring the gnarly math efficiency to the business.”

Ubercab, as it was called, was launched in early 2009 with “90 percent of the original vision there,” Camp recalled last year in an interview at a tech conference. Kalanick was involved only on a part-time basis, until he took control the following year as he recognized the company’s potential.

Camp, who in recent years has stepped back into an advisory role, credited Kalanick with leading Uber to some of its greatest innovations, including Uber Pool, which offers lower rates for shared rides, and the push into driverless vehicles.

In recent years, Kalanick had hinted at even greater ambitions, saying he considers Uber to be in the early days of becoming a robotics company.

On Tuesday, hours before Kalanick’s resignation, Camp published a post on the website Medium arguing that Uber’s problems were “growing pains.”

“Over the years we have neglected parts of our culture as we have focused on growth,” Camp wrote. He noted that Uber had a new executive team in place, appointed in Kalanick’s absence, but his post failed to mention what would happen to his co-founder.

AGGRESSIVE TACTICS

Kalanick knew how to grow a company.

He had displayed a fierce entrepreneurial streak since he was a teenager. The summer after graduating high school, he sold knife sets door-to-door in Los Angeles, where he grew up in an upper middle-class home, and tutored students for the SAT. (Kalanick had told Calacanis he scored an impressive 1580 out of 1600 on his SAT.)

As a freshman at UCLA, he launched his first company – an SAT prep course. He then started his first tech company, a file-sharing service called Scour, which brought him the attention of both curious investors and the entertainment companies whose movies and songs his service allowed to be traded among computer users. Scour was sued for billions of dollars and forced into bankruptcy protection.

That led to his next venture, Red Swoosh, a networking company, which was acquired by Akamai for $23 million in 2007. It also introduced Kalanick to one of his earliest mentors, tech investor and sports team owner Mark Cuban.

“He was driven. Smart. Relentless. He was willing to do any job, and he did,” Cuban recalled.

But Cuban, like a couple of other people contacted for this article who knew Kalanick in the early days of his tech career, said he has not spoken to Kalanick in years. Some Uber investors said Kalanick has become difficult to reach, too.

The same sharp-elbowed, aggressive tactics that allowed Uber to expand rapidly worldwide also earned Kalanick a fair number of enemies.

Sarah Lacy, a veteran journalist who founded the Silicon Valley news site PandoDaily, recalled how she and Kalanick started out as friends before Uber took off.

At a dinner party in San Francisco, she heard Kalanick describe this new service he was launching. She loved the idea. Getting a cab was impossible. She said the taxi industry was ripe for disruption.

“He was talking this big game about destroying the world – disrupting cabs – but I thought he was harmless,” Lacy said. “I underestimated his skills.”

As Uber grew, Lacy and her writers repeatedly clashed with Kalanick and the company. They wrote articles critical of how Uber treated its drivers and how female riders, in particular, faced harassment. The tension boiled over in 2014 when a BuzzFeed journalist heard Uber executives float a plan to research the private lives of writers whose coverage they did not like, particularly Lacy.

“They wanted to go after my family,” Lacy said. “I’ve been in the valley for 20 years. This is not normal.”

The backlash against Uber was immediate. Kalanick and other Uber leaders apologized.

But the company’s aggressive, no-holds-barred culture seemed to continue at the company, leading to a fresh wave of crises this year.

FACING PROBLEMS

In mid-February, as Uber was still dealing with a “Delete Uber” social-media campaign that took off when it appeared the company was profiting from an airport protest over President Trump’s first immigration ban, a former Uber engineer published a blog post titled “Reflecting on one very, very strange year at Uber.”

Susan Fowler described being hit on by her supervisor on her first day on the job, a human resources department uninterested in her complaints and a workplace where back-stabbing and ruthless competition were the norm.

The post might have been dismissed as the wild musings of a disgruntled worker. But it bulleted across Silicon Valley and beyond, illustrating how fragile Uber’s reputation was in the tech world. Within days, Kalanick was publicly apologizing and said a law firm would delve into Uber’s culture.

The next month, Kalanick was standing in front of that group of female engineers. And Fowler’s allegations were just one of the problems his company faced.

In the preceding weeks, Google’s Waymo had sued Uber claiming it used stolen technology in its driverless cars, and Uber executive Amit Singhal had been forced to leave after it was learned he had failed to disclose sexual-harassment allegations at his former job at Google.

Days earlier, Kalanick had to apologize for a video of him arguing with an Uber driver in San Francisco over whether the company had cut pay for drivers.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.