Marguerite Thompson Zorach has always reminded me of Suzanne Valadon. Most art fans don’t recognize Valadon’s name, but we have all seen her. She was the mother of French painter Maurice Utrillo and appears as a model in paintings such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s “Dance at Bougival” (1883) and “Girl Braiding Her Hair” (1885). Bright and talented, she was encouraged to pursue her own art by Edgar Degas. Valadon had talent and drive. In 1894, she became the first woman painter admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

More than for her own art, Zorach is probably better known as the mother of Dahlov Ipcar or as the wife of William Zorach, whose sculpture is now being featured in the Portland Museum of Art’s main gallery. That said, the couple is often spoken of in the same breath as “the Zorachs,” and Marguerite’s work has appeared in an ever-increasing number of major exhibitions. In my review of the Portland Museum of Art’s (PMA) excellent 2016 “Women Modernists in New York,” I noted that, in terms of work in the exhibition (for me at least), Zorach led her peers: Georgia O’Keeffe, Florine Stettheimer and Helen Torr.

One thing that troubled me, however, was the assertion in the PMA label copy that Marguerite often turned to embroidery because she didn’t have the time as a homemaker mom to go into the painting studio. The statement was neither careless nor unfounded, but it didn’t sit right. Her embroideries, after all, clearly took more time than most painters spent on a painting. The Farnsworth Art Museum’s exhibition “Marguerite Zorach – An Art-Filled Life” offers a solution to the riddle. The exhibition includes a pair of echoing images, both titled “Indian Wedding” with one hung above the other, depicting a wedding procession in India with a black elephant at the center. The 1910 painting is jovial and jaunty but, with its thick lines and flat colors, it is simple and quick.

On the wall is a statement by the artist in which she explained that she thought her paintings needed something more, and she found that something with embroidery.

The wool embroidered on linen work opens up with a richness of texture and subtle complexity of intertwining rhythms. The physicality fits. The embroidered piece pops with a presence that far outstrips the painting. The regalia, excitement, visual richness and even a sense of playful pomp all fall in line with the visual parade of the wedding.From that moment, Zorach’s embroideries take over the show. When they are hung side by side with her paintings, we get enough of a sense of Zorach’s embroideries to follow them as paintings in Zorach’s own woolly palette of colors, textures and rhythms.

“Land and Development of New England,” by Marguerite Zorach, 1935, oil on canvas, 96 by 76 inches, collection of Farnsworth Art Museum.

And Zorach could paint. Her self-proclaimed proclivity for “decoration” appears to have given her an easier aesthetic path into complex stylistic movements such as Cubism and Art Deco than most other artists. Her circa 1911 “Café in Arles,” for example, proves she had a charmingly complete handle on van Gogh and Maurice Prendergast. If she stayed in that mode, she would have made many great paintings. Her 1916 “Justin Jason (Shoe Shop Window),” her 1917 “A New England Family,” and her 1922 “Shore Leave,” among other works, reveal an understanding of Cubism that easily incorporates some of the movement’s trickiest aspects, such as transparency and the simultaneous use of a single shape in multiple objects.

“Shore Leave” is also one of a group of works in the show that hint at a complex take on female sexuality. The agency in the image belongs to the pretty woman in the yellow dress who takes center stage, not the sailor whom she seems to be passing by if she so chooses.

More obvious, but no less impressive, are Zorach’s female nudes. Very rarely are her painted female nudes idealized. They are buxom, healthy and strong; they are self-contained and confident. This includes the nude female in “Prohibition” (1920), a striking image insofar as it features two suited men conversing and drinking at a table with a nude woman before them, none of them, so it seems, particularly concerned about the other (or anything else for that matter). The easy read, in light of the title, is a red-walled brothel. But Zorach is playing another game as well – taking on Édouard Manet’s seminal 1863 “Luncheon on the Grass,” which featured two suited men, a nude woman and a still life all set in a pastoral landscape. It’s an intentional mash of painterly genres.

Zorach herself moves across genres with unusual ease and grace. She has no problem with landscapes, portraits, still lifes, nudes, domestic interiors, large history paintings such “Land and Development of New England” (1935) or the many family scenes, such as her 1924 “Family Scene.”

“Nude,” by Marguerite Zorach, 1922, oil on canvas, 40 by 30 inches, Worcester Art Museum.

But it is the embroideries that set Zorach apart. About one-third of the works in “An Art-Filled Life” are fiber, primarily embroideries, but with a few hooked rugs and an impressive batik silk scarf.

The embroidery “My Home in Fresno Around the Year 1900” (1949) is denser and far more complex than most paintings. It calls to be seen as a painting in terms of structure, detail and intellectual complexity. It might be mistaken for nostalgic recollections, but the sleepy nude in the hammock in the lower right is undoubtedly Zorach herself. Her presence beckons us to read this as a dream diary rather than a self-consciously scrubbed memoir.

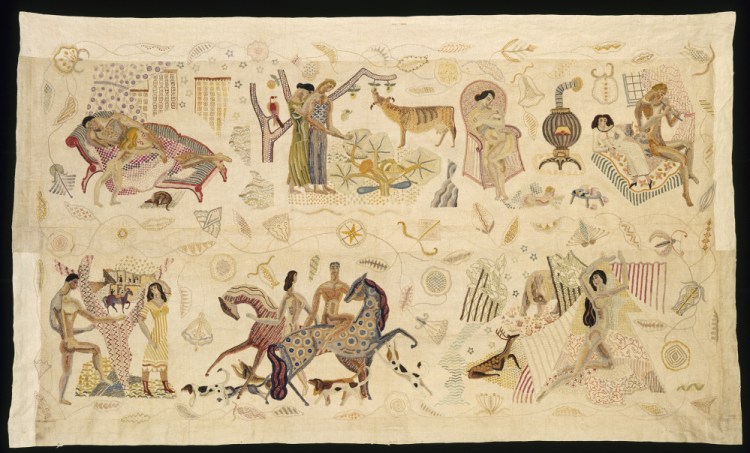

“Maine Islands” (1919) and “Home in Maine” (1925) are slender horizontal scenes. The first is idyllic, calm, a traditional coastal landscape scene bookended by nude figures on each side: a father and child on the left and two women with a dark horse (or dog?) on the right. The second also features Zorach’s quirky penchant for presenting her embroidered characters as nudes – whether in the landscape or sitting with the family for dinner. It’s odd when you dwell on the idea, but the works flow so naturally, it’s easy to miss. And while it could be seen as an Art Deco affect, Zorach was doing this before Art Deco – which is generally considered to have started about 1920. Considering her husband’s role as a leading Art Deco sculptor, it raises an intriguing question about who inspired whom.

“Woolwich Marshes,” by Marguerite Zorach, c. 1935, oil on canvas, 21 by 26 inches, Portland Museum of Art.

The most striking object in “An Art-Filled Life” is a large commissioned embroidery, “The Family of John D. Rockefeller Jr. at their Summer Home, Seal Harbor, Maine” (1929-1932). It is a complex image that flows between scenes of various members of the Rockefeller family pictured at their preferred pastimes.

The works that ring the most true, however, are the embroideries Zorach made for her family. These are happy interior scenes of a busy and active family, bubbly to the point of dancing.

One of these is “The Ipcar Family at Robinhood Farm” (1944). Marguerite bends over the stove. William, shirtless, sculpts (or is he ironing?), a child plays in the foreground next to a dalmatian, and the baby smiles from the highchair. It is this embroidery that Zorach’s daughter Dahlov Ipcar depicts in her mother’s hand in the portrait of Zorach at the center of the show. It is a warm and fitting portrait. Ipcar portrays her mother as matronly, pretty, calm, domestic, creative and productive.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.