For six days, Micheal Cochran’s body lay hidden under charred debris.

In the predawn hours of Feb. 18, 1981, a spectacular fire destroyed a cabin in Dedham, a pass-through town southeast of Bangor.

Fire investigators didn’t have a chance to get to the scene the next day. Or the day after. Or for the next three days. They were busy at another, much bigger fire scene nearby, and didn’t know there might be victims in Dedham.

Cochran’s death was ruled accidental at first. He must have suffocated from the smoke, investigators figured.

But details suggested otherwise. There was the man seen running from the cabin when firefighters arrived. There was the drug bust in nearby Holden that involved some people who knew Cochran well. And there were the empty gas cans.

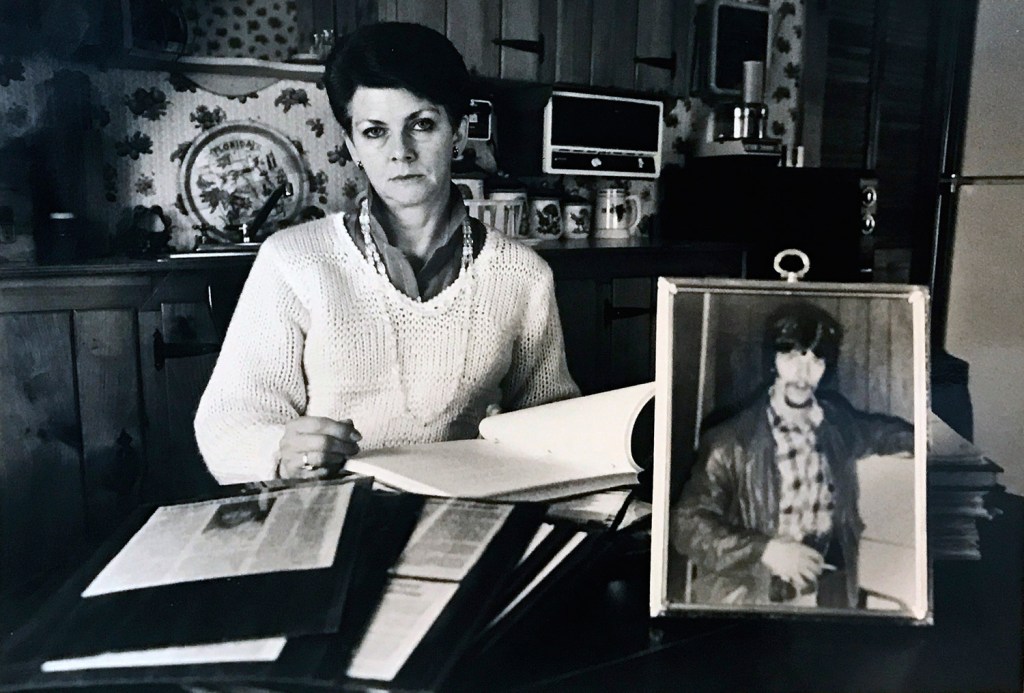

Leola Cochran’s son was already cremated by the time police reclassified his death as a homicide a few months later. The fire was intentionally set, she was told, and Micheal may even have been killed before flames destroyed the cabin.

The news leveled her.

In his 24 years on Earth, Micheal Cochran hadn’t built the best reputation. He lost interest in school at a young age and gained interest in drugs. He had a growing criminal record, much of it fueled by his drug habit, and was a fugitive at the time of his death.

None of that justified his end, his mother said.

“I don’t care who you are, nobody deserves that,” she said through tears. “He was my son.”

In the 36 years since Micheal was killed, she has pored over every detail of the murder and the ensuing investigation. She has devoted more time than any of the many detectives who have been assigned to the case, which has long since turned cold.

The hardest thing for Leola Cochran isn’t that she’ll never know who was responsible. She’s confident she knows who killed her son.

Her worry is that detectives squandered their chance to charge his killers and bring her peace.

Micheal Cochran, 19, poses with his girlfriend, Linda Gray, who was with him in 1980 when he escaped from a Bangor courthouse.

Micheal Cochran’s is one of about 80 unsolved homicides assigned to the Maine State Police’s cold case squad. Long dormant, the squad was resurrected two years ago and has breathed life into old cases. Coupled with advancements in investigative resources, including better DNA analysis, police have more resources than ever.

There have been some results, too.

Last year police made an arrest in the 1980 killing of a teenager from East Millinocket. This year a Farmington man was arrested for allegedly causing the death of his infant son 38 years ago – a death originally thought to be accidental that was quietly reopened as a homicide investigation in 1991.

Most cold cases, though, stay cold. Sometimes police may have a good idea who did it but simply can’t collect enough evidence to bring charges. Sometimes investigations are mishandled. Leola Cochran believes investigators grossly mishandled her son’s case, from failing to treat the fire as a crime scene to neglecting to interview people who might have been able to piece the events of that night together.

Kenneth MacMaster, a former Maine State Police detective who wasn’t assigned to the Cochran investigation but knew the victim and many of the people involved, agreed with the victim’s mother that the case was mishandled. In an interview last month, he called the case a “travesty of justice,” and said the details were etched into his memory.

After MacMaster offered to share those details, though, he stopped returning a reporter’s calls and emails.

The Maine Sunday Telegram reviewed hundreds of pages of documents, some obtained by Leola Cochran through legal proceedings, as well as old newspaper clippings about the case. The Telegram interviewed Leola Cochran multiple times, as well as attorneys and detectives who were involved, some of whom would not speak on the record because they were not authorized to discuss an open case.

That review revealed a murder investigation that was troubled from the beginning and got worse.

Micheal’s body wasn’t found until six days after the fire, which means the murder scene could have been disturbed in that time. His body was cremated, so there was no opportunity to conduct any forensic work, even years later. Perhaps most important, the people questioned in connection with his death, including those who were with him that night, were unreliable. They were all drug dealers or petty criminals willing to turn on anyone. Their stories were inconsistent.

Lt. Troy Gardner, one of the cold case squad’s two supervisors, declined to discuss any specifics of the Cochran case, as is customary.

“There are challenges we deal with in any investigation,” he said. “The age of this case and the fact that people involved may have forgotten things or passed away, that’s certainly a challenge.”

Leola Cochran hasn’t forgotten. While everyone else involved has largely moved on, she has been stuck in suspension.

“I’m never far from it, which means I’m never far from Micheal,” she said. “I’ve had people say to me, ‘You need to let go of all that.’ I can’t. I just can’t.”

Leola turned 81 this year. She has begun to accept the probability that she may not get any answers about her son’s death before her own.

Over the last several years, she has written a book detailing everything she’s learned about her son’s killing and the 36-year aftermath. Lawyers are reviewing it for potential libel ahead of publishing.

“The only justice I’m going to get is by telling my story,” she said.

Christmas 1971: Mike, right, is pictured at 15 with members of his family, including his father, Derald Cochran Sr., center. He was a good-natured boy, but trouble found him.

Micheal Cochran was born Oct. 4, 1956, to Leola and Derald Cochran Sr. He grew up on a potato farm in Aroostook County with his parents, an older sister and an older brother.

Micheal was good-natured and respected his parents, but trouble found him. He struggled in school and then lost interest. Had he grown up in a different era, he might have received special help in school, his mother said. Instead he was ignored.

In 1969, when Micheal was a teenager, the family moved south to Brewer, from a sprawling farm to a crowded mobile home park. None of the kids was happy about the move, Leola said.

He was teased about his learning disabilities, which made school even less appealing. He discovered drugs at a young age – 13, his mother figures – and started stealing around the same time.

In 1970, Micheal’s older brother, Derald Jr., dropped out of high school and joined the military. Their parents moved their mobile home to a private lot in Eddington, a small town nearby.

Micheal attended Brewer High School in the fall of 1971 but didn’t last the year and never went back. He was 15. After that, he ran away often. He would hitchhike with a framed backpack carrying everything he needed. When he was 17, he made it all the way across the country to California. After his return, his mother found the cover of a San Francisco phone book.

That same year saw his first criminal conviction. He broke into a house and stole a bunch of coins. He was sent to a juvenile detention facility, which his mother hoped might straighten him out.

It didn’t.

Not long after his release from juvenile detention, he boosted a car and drove out of state. He was caught. He stole a blank check from his sister and tried to cash it for $50. He broke into his grandmother’s house in Aroostook County and took her color TV as well as food from her freezer.

At this point, Leola believed Micheal’s drug habit was fueling his crimes.

She didn’t know how bad it had gotten, though, until August 1976, when a friend of her son came to her house in a rage. Micheal had stolen his drug proceeds, the man said, and he threatened to kill him. Leola was terrified that her son had gotten in deep with a group of ruthless drug dealers who operated in Greater Bangor.

Micheal had fled the state again. He was eventually arrested in Nevada and extradited back to Maine to face charges.

Police offered him a lesser sentence if he would provide information about the dealer he stole from but Micheal refused. He spent about six months incarcerated and then, a little more than a month after his release, was arrested again for trying to sell stolen items. He went back to prison for an additional 18 months.

As much as she hoped prison would change him, Leola said Micheal soon went back to drug dealing. He was caught in March 1980 with two others at an apartment in Brewer, where police found two pounds of marijuana, 350 amphetamine tablets and 150 tablets of LSD.

MacMaster was one of the DEA agents who brought him in.

While out on bail and awaiting sentencing, Micheal returned to his parents’ home late one night to pick something up. His mother was awake. He admitted to her that he was addicted to cocaine and that he hated his life.

Leola told him to get help and that she would support him, but he left.

In December 1980, Micheal appeared at the Penobscot County Courthouse in Bangor to be sentenced on the drug charges. He was represented by a local attorney, Andrew Mead, now a Maine Supreme Court justice. Mead, through a court representative, refused to discuss the case.

His mother didn’t attend the hearing, but Micheal’s then-girlfriend, Linda Gray, was there.

The judge, taking Micheal’s growing criminal history into account, handed down a lengthy sentence – five years. Before he was led away by a bailiff, though, Micheal ran. He vaulted over the stairs inside the courthouse, injured his ankle during the landing and then hobbled toward the door.

Gray later told Leola Cochran she heard a sheriff’s deputy call out to him, “Stop, or I’ll shoot.”

Micheal didn’t stop, but the deputy didn’t shoot, either.

“Sometimes, I think that would have been a more humane death,” the mother said.

Micheal Cochran and his girlfriend, Linda Gray, hang out at a friend’s house in the hours before Micheal was slain in 1981.

Leola Cochran didn’t hear from her son after his escape and said she doesn’t know where he went.

A few days later, Gray delivered a handwritten note from Micheal.

“Mom, I know it was probably wrong to run, but I can’t handle 5 or 7 years in Thomaston (Maine State Prison), and I will make it I promise,” he wrote. “I love you and Dad a lot and I wish we could all be together, but I got to try and keep my freedom.”

He left the state for a while with Gray, according to his mother, but eventually returned to stay close to Bangor.

R. Christopher Almy, who was a young prosecutor at the time and is now the longtime district attorney for Penobscot County, said drugs were prevalent in Greater Bangor and fueled much of the crime.

“It wasn’t like the opioid crisis of today where you had a lot of people addicted, necessarily,” he said. “People just liked to do drugs.”

The drugs came into Maine the way they still do today – often by car up Interstate 95 from other states – but there was a local network of distributors. One of the leaders was a man named Lionel Cormier.

Although Cormier had a lengthy drug history by the early 1980s, he also liked to steal. Specifically, he liked to steal from drug dealers. It was the perfect crime. No drug dealer would report a robbery to police.

But Cormier had a violent side, too. He threatened to kill the family members of anyone who snitched on him. During one robbery, he cut off a victim’s ear.

Cormier ran with a few different people at that time, according to police records and court documents, including brothers Percy and Richard Sargent, Paul Pollard, and David Dupray.

Micheal Cochran was part of that group too, though Leola said they didn’t all trust him.

But those drug connections did afford him a place to stay when he was on the lam.

Dupray’s mother, Rose Kenney, owned a cabin on Phillips Lake in Dedham – just far enough outside Bangor for people to lie low.

Leola Cochran learned later that Percy Sargent and Pollard were at the cabin the night before it burned, as was Gray, Micheal’s girlfriend.

But her son was the only one who died.

The night of the fire, a drug bust took place in Holden, the next town over. Percy Sargent and Dupray, who both had been with Cochran hours earlier, were arrested.

A few hours before that, firefighters were alerted to a massive fire at an apartment building on Main Street in Bangor. Dozens of people were evacuated, but three people died from smoke inhalation.

Investigators determined quickly that the Bangor fire was arson.

Not much was reported about the victims at the time, and it was never clear if they were targeted or were accidental victims. The building housed businesses on the first floor and offered cheap rooms for rent on the second and third floors. The clientele often was rough. No one was ever arrested, and the case is now closed.

But the fire in Bangor tied up state fire investigators for days.

That’s why Cochran’s body wasn’t discovered until almost a week later by State Fire Marshal Wilbur Ricker, who arrived in Dedham to inspect the remains of the cabin.

Leola Cochran has long fretted over that delay. She said firefighters must have known enough before then to suspect foul play. The fire was clearly intentionally set, as evidenced by the intensity of the flames and the presence of gas cans at the site.

And there was the revelation from Norman Herrin, who led the local volunteer fire department that responded that night. “As I arrived on the scene, and being the first one on the scene, I did see an individual leaving the area through the woods,” Herrin said at the time.

Four years later Pollard, who had a lengthy criminal history, admitted to police – during an investigation of another crime – that it was him, but he denied setting the fire or killing Cochran.

Still, Leola has always wondered, why didn’t police take more seriously the fact that someone was running from the fire scene?

“If firefighters had checked through the ruins as they do in a normal fire, the body probably would have been discovered,” Herrin said.

But that wasn’t what happened.

Minutes after Ricker found the human remains, two men approached the property in a car and got out to survey the rubble.

“I didn’t want them to know what I’d found, and so I just stepped right out from behind the door in uniform, and they looked like two deer got caught under a jack lantern or something, and they kind of froze there and all I had was the piece of a film case and my pen,” Ricker later said.

From the beginning, Leola Cochran always felt outside her son’s murder investigation.

Micheal was a fugitive from justice at the time, and police weren’t sure they believed Leola when she told them she didn’t know where he was.

“If I’d known where he was, I wouldn’t have left him six days under a pile of rubble,” she said.

Almy, the Penobscot County prosecutor at the time, said he still remembers how upset she was but he understood.

“I think it was just one of those cases where (police) didn’t have a lot of evidence to go on,” he said.

Leola Cochran has always believed that police mishandled the case. Pollard was interviewed, albeit much later, but Cormier and Percy Sargent were not. She couldn’t understand why.

Early on in the investigation, she asked her son’s attorney, Andrew Mead, what he thought happened to him. His answer stunned her.

“Stay away from that, Ms. Cochran,” she said he told her.

But she didn’t. The circumstances of her son’s death consumed her. The more she thought about it, the less it made sense. Why didn’t they inspect, or fingerprint, the gas cans that were found at the property?

As she learned more about her son and the people he associated with, police often kept her in the dark about their investigation.

Nearly three years after the murder, surprisingly, a grand jury delivered indictments against three men for the murder of Micheal Cochran: Richard Sargent, Roger Johnson, who went by “Bubba,” and William Meyers, ominously nicknamed “Doomsday Express.”

All three were involved in the drug game in Greater Bangor. Sargent’s brother, Percy, was with Micheal at the cabin the night before it burned.

No one told Leola Cochran that suspects had been charged. She found out by reading the newspaper.

But that case quickly fell apart. The state’s case hinged significantly on the testimony of one witness, Sharon Sargent, the sister-in-law of Richard and Percy Sargent. A habitual drug user and sometime police informant, Sharon Sargent told police that she was at a party the night of the Dedham fire and overheard plans to have Cochran killed. The three men suspected Cochran of being a snitch, she said, and were going to take care of him.

It turns out that there was an informant for the drug bust that night, but it was not Cochran. It was Percy Cote, a low-level dealer who had been working with drug agents.

In June 1985 the state dropped the charges against the three men charged with Micheal’s murder.

Thomas Goodwin, who was a Maine assistant attorney general, said at the time the decision had to do in large part with Sharon Sargent’s inconsistent testimony. She is now deceased.

Goodwin, who is now retired, said it’s unusual for a case to fall apart like that, especially a murder case. He also doesn’t dispute the opinion of MacMaster, the former state police detective who called the case a “travesty of justice.”

“If he thought the case was mishandled, I’d be inclined to believe him,” Goodwin said.

Leola Cochran was devastated after charges were dropped against the three men. She was never convinced they killed her son, but either way she believes law enforcement failed.

She wasn’t sure she’d ever find her son’s killer. But she kept reading the papers, looking for certain names.

In 1986, she learned about a major robbery trial she hoped would shed light on her son’s case. That trial involved Cormier, Pollard and the Sargent brothers.

They were suspected of robbing, on two occasions, a drug dealer named Charles Dolan, who lived in the remote town of Corinth, northwest of Bangor. The crimes occurred over a three-month period between late 1980 and early 1981, overlapping the time Cochran was killed, according to court documents.

Between the two robberies, more than $50,000 in cash was taken. In the second, Cormier beat Dolan mercilessly as Dolan begged him to stop.

“You wait ’til you see what I do to you now,” Cormier said, according to court documents. He then took out a knife and cut Dolan’s left ear off. The victim didn’t realize what had happened until Cormier dropped the ear on the floor in front of him.

Pollard testified as a state’s witness. He had initially been interviewed by Sgt. Barry Shuman, the lead detective in the Cochran murder, about that case but instead gave information about Cormier.

During the trial, Cormier, likely as a way to get back at Pollard, “sought to introduce evidence that implicated Pollard in the murder of a Micheal Cochran.”

That led to Pollard admitting he was at the cabin the night of the fire and that he was the man seen running from the flames. But he said he had nothing to do with Cochran’s death.

Cormier was found guilty of the robbery. Pollard avoided prosecution in exchange for his testimony.

Cormier’s robbery trial was illuminating, but it only confused Leola Cochran more. She was convinced she was close to the truth and couldn’t stop.

At her own expense, she decided to sue Paul Pollard. She couldn’t allege murder in a civil case but she could allege wrongful death and claim that Pollard’s negligence contributed to her son’s death.

During discovery in the civil trial, Leola obtained tapes of conversations and statements from some of the people involved, including Percy Sargent. She has been told by police that they would not hold up in court in a criminal case.

The lawsuit also allowed her attorney to depose Linda Gray, Micheal’s girlfriend, who inexplicably had never been interviewed by police. Gray said she had no memory of that night. She said she left Micheal at the cabin because she had to get up early and go to work the next day.

Detective Shuman testified as well, although he effectively sided with Pollard.

Leola said she doesn’t know why, although she suspects that police had given Pollard blanket immunity in the Cormier robbery case.

Although the standard of proof in a wrongful death suit – preponderance of evidence – is lower than the threshold for murder, Leola lost the case.

Shuman died in 2005. Ralph Pinkham, another detective who worked on the case throughout the 1980s, is retired and lives in Hancock County. He did not return multiple calls for comment.

In 2002, more than two decades after the murder, Maine State Police assigned a new detective to the case, Gerald Coleman.

Leola Cochran was reluctant to sit down with another detective. When they did meet, he told her the investigative file on her son’s case was thin. He then asked for her documents. She had amassed more intelligence than police by that point.

That same year, Leola Cochran’s younger son, Derald Cochran Jr., got a letter from William Stokes, then head of the Attorney General’s Office criminal division. Stokes explained the challenges and seemed to acknowledge that police knew who killed Micheal but didn’t have enough prosecutable evidence.

“If we bring a case to trial and we lose, that is the end of it,” he wrote. “Thus, there is a significant difference between solving a case in the law enforcement sense and being able to prosecute a case in a court of law.”

Stokes is now a judge. He declined to comment through a court representative.

Leola Cochran, however, said Coleman told her that he could have solved her murder on day one if he had been assigned the case then.

He narrowed his focus to Lionel Cormier, who, even after spending time in and out of prison for robberies and other drug-related charges, hadn’t changed.

Coleman couldn’t pin the murder on Cormier, but he did help put him behind bars for life. With Coleman’s help, federal prosecutors in 2003 charged Cormier, along with three others, with robbing a couple in Orland of their illegal drug stash, mostly prescription painkillers.

When Cormier was sentenced for that crime in June 2005, a federal judge called him a predator.

Gail Malone, then assistant U.S. attorney, said at his sentencing that Cormier had bragged in the past about killing Micheal Cochran.

Cormier didn’t deny having a role in Micheal’s death but accused Malone of “clouding the water,” according to an Associated Press story.

“I’ve been in jail all my life,” he told the judge. “You think I need the government to throw their weight on me? That’s ludicrous. Just save a spot in the cemetery for me.”

The conviction of Cormier was welcome news to Leola Cochran, even if it wasn’t for her son’s murder.

But she was never convinced he acted alone.

Her son’s case remained open. Were others walking free?

In a Sept. 5, 2006, letter to Leola from Stokes in response to a letter she had written, the state finally acknowledged what she had known for years. “Detective Coleman has done outstanding work on this case but there remains tremendous difficulties with prosecuting this case particularly in view of the fact that the ‘homicide scene’ was not treated as such until a significant period of time after your son’s death, potentially jeopardizing important evidence in the meantime,” Stokes wrote.

After 25 years, the state’s top homicide prosecutor admitted that police had bungled the investigation from the beginning.

In 2007, Leola wrote to Cormier. He was in prison and in bad health. She thought if he was ever going to unburden himself, that would be the time.

But the letter went unanswered. Cormier died in prison two years later.

Coleman ended his investigative career, too, and now works in the protective detail for Gov. Paul LePage.

By October 2011, Leola Cochran was dealing with another detective, Troy Gardner.

He told her that the case was still open and revealed that a detective was planning to travel out of state to meet with a woman named Karen Murray, Pollard’s girlfriend at the time of the murder, who had never been interviewed. Depending on that interview, Gardner wrote, police would consider re-interviewing Pollard.

She doesn’t know if that ever happened. Pollard now lives in California. Messages left for him were not returned.

Attempts to find Percy Sargent, who was with Micheal Cochran the night he was killed and who she believes has answers about his death, and his brother, Richard Sargent, who was once charged in the murder, were unsuccessful.

David Dupray, whose mother owned the cabin where Micheal perished, died this year.

The case has taken a toll on Leola. In 1982, about a year after Micheal was murdered, she and her husband divorced.

“He lived (Micheal’s death) once,” she said of her ex-husband. “I live it every single day.”

Three years ago, Leola Cochran moved from Maine, where she had lived her entire life, to be closer to her youngest son, Shawn.

In April, Leola got a letter from Renee Ordway, the liaison for the cold case squad. It didn’t say much, other than that there were no new developments.

Leola said she’s glad the state has put a spotlight on unsolved homicides, but she’s not hopeful it will make a difference in her son’s case. There is no possibility for DNA analysis. Old criminals are unlikely to have a revelation about a night nearly 37 years ago.

Some cases just stay cold.

“I think it’s one of those cases that’s not ever going to get solved, unless someone is on their deathbed with cancer or something and decides to come forward with information,” said Jerry Goldsmith, a defense attorney who represented Richard Sargent in the 1980s.

Leola said she has found some peace by putting her son’s story – her story, too – in writing.

“I have a good life,” she said, “but this is my struggle.”

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

Twitter: PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.