There was a strange sense of deja vu in the Supreme Court Tuesday morning. Twenty-five years ago, Colorado voters passed Amendment 2, which nullified protections for gay people statewide, and which the Supreme Court later struck down. In Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, which was argued Tuesday, the religious conservatives who pushed for Amendment 2 sought to undermine civil rights protections in another way – by claiming that the Constitution gives them the right to discriminate against gay people.

Masterpiece arose when Lakewood baker Jack Phillips refused to provide a cake for a same-sex wedding. The couple filed a complaint with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, which held that Phillips had violated the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act (CADA). Phillips responded by saying that applying CADA to make him use his artistic talents to bake a cake for same-sex couples violated his constitutional rights to free speech and religious conscience.

The case, though, is about more than just cake – it is an important and dangerous battle in the broader war between religion and speech rights that conservatives claim on one hand, and LGBT rights, contraceptive access and compliance with health-care laws on the other.

Many justices seemed sympathetic to the baker: Noel Francisco, President Trump’s new solicitor general, claimed that leaving the law intact would mean that an African-American sculptor could be forced to make a cross for a Ku Klux Klan event if he made crosses for the general public.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who holds the court’s key swing vote and who penned the decision that recognized same-sex couples’ right to marry, remained troubled. As he pointed out, Francisco’s position would essentially permit a “boycott (of) gay marriages.” If the court recognized the baker as an artist who had a constitutional right to refuse to make a cake for same-sex couples, then what’s to stop a chef, or florist or makeup artist from claiming that same right? The baker’s lawyer unconvincingly tried to cabin the case to its facts: Neither a makeup artist, nor a hairstylist, nor even a chef engaged in work sufficiently artistic enough to merit free speech protections.

But there are other ramifications of ruling for the baker. If gays can’t be protected from discrimination, then how about blacks, or women, or discrimination based on national origin, or religion? As the couple’s lawyer pointed out, if claiming a speech or religious right gave one an out every time someone came across a law they didn’t like, “you’re in a world in which every man is a law unto himself.”

Francisco’s suggestion that race was special did not seem to get much traction with the justices.

Thus even the conservative justices found themselves in a hard position.

They could rule against a sympathetic baker who served gay couples in general, but just refused to make them a custom wedding cake, or rule in his favor, thus opening a Pandora’s box, that would, as Justice Stephen G. Breyer put it, “undermine every civil rights law since year 2.” A ruling in favor of the baker could effectively nullify hundreds of anti-discrimination laws across the country, including signature protections like the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Even Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, Trump’s appointee, pressed Francisco for a test that would help draw a line that would avoid that outcome.

And Justice Kennedy seemed torn, lamenting that blatant discrimination would be an “affront to the gay community,” but at the same time accusing the state of Colorado of being neither “tolerant nor respectful of Mr. Phillips’ religious beliefs.”

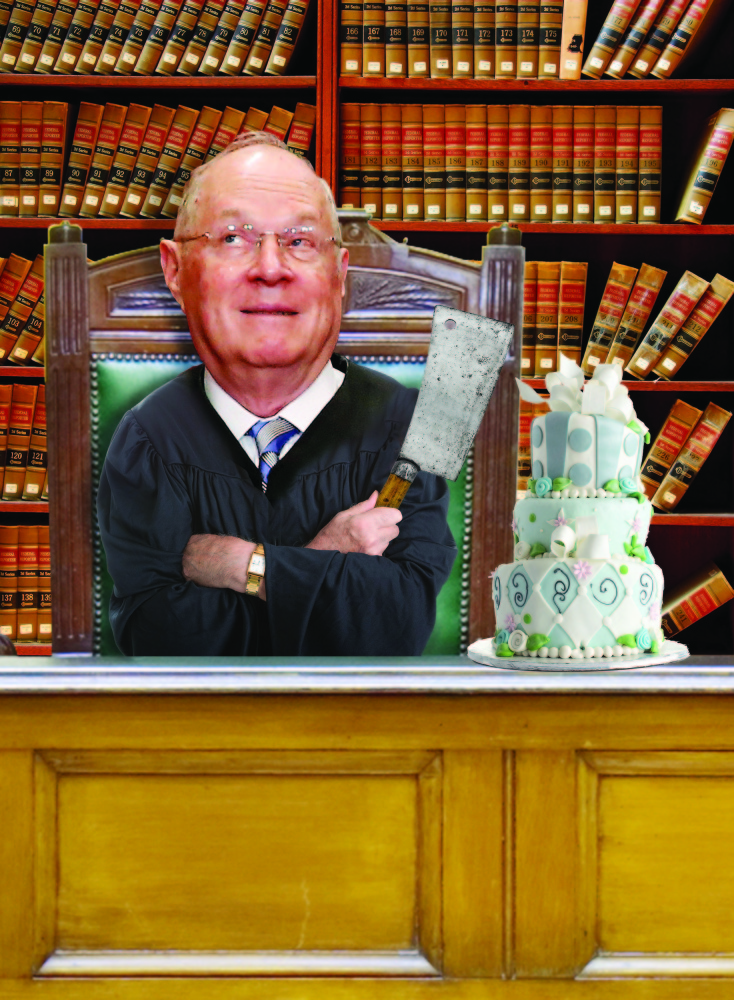

It was Kennedy’s line of questioning, however, that suggested a possible Solomonic outcome.

In a tense series of questions, Kennedy suggested to Colorado’s solicitor general that the state had shown “hostility towards religion” in ruling against Phillips.

Kennedy focused on a single statement in the case’s voluminous appendix, in which one of the seven members of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had said that using religion “to justify discrimination is a despicable piece of rhetoric.”

The tone and nature of Kennedy’s questions suggest that he is inclined to rule for the baker. But his ruling would effectively still be a win for gay rights laws.

Kennedy can hold that CADA itself – like hundreds of other civil rights protections – remains completely valid. But this particular proceeding, he might conclude, was infected by anti-religious bias.

The court could send the case back for a redo, or simply invalidate the commission’s finding.

The religious right wants a free-standing exemption from civil rights laws. Gay rights advocates (correctly, I think) want the court to resoundingly affirm the vitality of civil rights laws.

So Kennedy’s ruling will probably satisfy neither side. But at the end of the day, any ruling that leaves civil rights laws alive, even if the Craig and Mullins lose this particular case, remains a victory for gay rights.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.