The city of Portland is apologizing to more than 200 patients previously enrolled in its HIV-positive health program for not telling them it planned to share their private health information with University of Southern Maine researchers.

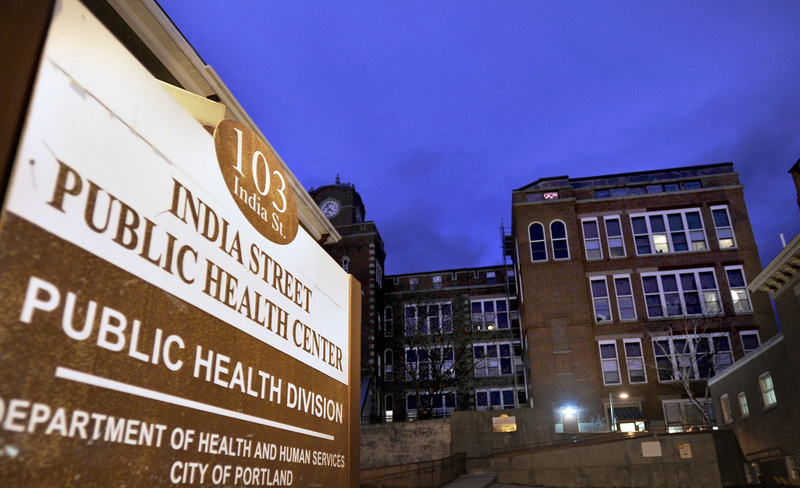

Two patients and two former health care officials say the city violated patient privacy by providing a list of the patients’ names, addresses and phone numbers to USM’s Muskie School of Public Service so it could conduct a survey on the city’s behalf. The survey was to examine the closing of the city’s HIV program at the India Street Public Health Clinic and transferring the grant that funds it to the Portland Community Health Center, and to determine whether there were any gaps in service.

One of the health care officials, Dr. Ann Lemire, former medical director at the India Street clinic, said she warned the city six weeks ago that it should not be sharing the list of patients with a third party.

In response to a request to interview city officials, City Hall Communications Director Jessica Grondin released a letter she plans to send to former patients, apologizing for mishandling the communications about the survey. But the city insists that its actions do not constitute a formal breach of HIPAA – the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which seeks to ensure that a person’s health information remains private – because of exemptions allowed for research and program evaluation.

“We have learned important lessons from this experience and are implementing new and updated policies and procedures for ensuring that our health care entities and programs better communicate with patients regarding uses and disclosures of their patient’s (personal health information) for these types of research, program evaluation and business associate-related purposes going forward,” said the letter signed by Dr. Kolawole Bankole, the city’s public health director. Bankole is also a member of the Muskie School’s Public Health Adjunct Faculty, according to USM’s website.

CLINIC CLOSURE WOUNDS REOPENED

While HIPAA is designed to protect patient privacy, it does contain exemptions that allow a medical provider to share information with qualified researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of a program, as long as certain conditions are met.

A national expert on patient privacy rules said a careful review of documented policies and disclosures signed by patients, and between the city and university, would be needed to determine whether any formal breach of HIPAA rules occurred.

The survey, which was shelved while the city looked into privacy complaints from two former patients, has reopened wounds associated with last year’s decision to close the Ryan White HIV Positive Health Care Program, which served many LGBT patients, at the city’s India Street clinic. The move was vehemently opposed by patients, several of whom told the City Council during hours of public testimony that the care and relationships they had established at the clinic could not be replaced.

The city nonetheless moved forward with the plan, transferring the federal grant that funded the program to the Portland Community Health Center, now called Greater Portland Health. City officials expected most of the clinic’s 229 patients would receive care at the new clinic, but an analysis in January showed that only 33 had done so.

One former patient was mortified when he received his letter from USM saying it was conducting a survey on behalf of the city. The letter, addressed to “participant,” said that “we got your contact information from the city of Portland.”

“I was shocked and horrified someone gave out this very sensitive and personal information,” said the 62-year-old man, who had been receiving care, including for a psychiatric condition, at the city clinic since 2002. The Portland Press Herald is not naming him to protect his privacy.

CITY HAD BEEN WARNED ON PRIVACY

The city has relied on a Patient Advocacy Committee to help guide the closure of the HIV program. Jenson Steel, a former patient who serves on the committee, was surprised to hear the city had given patient information to USM. He said the committee was told the city would be mailing the surveys to patients on behalf of USM, and that the school would only receive anonymous information.

“As far as I know, this was done anonymously with USM and it was mailed by the city,” Steel said.

The city did not directly address an emailed question about who collected the patient names and contact information and provided them to USM. It also disputed Steel’s assertion that the patient committee was told the city, not USM, would be mailing the surveys to patients.

Two former health officials who oversaw the clinic also were surprised that the city created a centralized list of patient names and contact information and provided it to USM.

Lemire, the former clinic’s medical director, said she shares the patients’ concerns. She said someone from the transition team, a group of city staff and former patients overseeing the clinic’s closure, contacted her about six weeks ago looking for the list of former patients of the city’s HIV clinic and where they were currently receiving care.

Lemire said she refused because the city was seeking personal information about “a stigmatizing condition and supplying this information to a third party – all without the consent of the patient.”

“I informed the person from the transition team that they should not pursue getting this list as it was a HIPAA violation,” Lemire said in an email. “If they did not believe me they should have contacted the Attorney General’s Office.”

Lemire said a similar request was made last year when the city was winding down HIV services at the India Street clinic. That time, the city requested that she send the list to Greater Portland Health, which took over the city’s federal grant. But Lemire said she refused and instead provided information to the city’s Health and Human Services Director, Dawn Stiles, about the Maine Medical Association’s guidelines for properly transferring patients.

“I applaud this patient for coming forward with his/her complaint for he/she is absolutely correct on all fronts,” Lemire wrote. “I feel our patients have been violated and continue to be treated poorly and without respect.”

Dr. Caroline Teschke, a former program manager at the clinic, agreed. She said she also stressed the importance of respecting patient privacy during the closure and for strictly adhering to the guidelines established by the Maine Medical Association for closing a medical practice. She said that India Street staff worked closely with patients to help them find new medical homes, set up their initial appointments and ensure they had enough medication.

“Every time the subject (of patient privacy) was raised by anyone, Ann and I were consistent, unanimous and unambiguous,” Teschke said. “I am very surprised at the fact that after city officials acquired these personal details for individual patients, the names and contact information were then released to a third party.”

Even when the clinic was open, staff was careful not to mail any information to patients’ homes without their permission, she said.

“We were acutely aware of how stressful and frightening this might be to individuals with a stigmatizing disease, especially when the communication came from an ‘official’ source,” Teschke said.

When the council wanted information last year about where patients ended up, Teschke said, India Street staff was careful to provide as much information as possible without including patients’ names and identifying information.

“This seemed to us a confidential and reasonable way to provide the council with information on the state of the transition without breaching HIPAA,” she said.

HANDLING OF DISCLOSURE TO USM

In the letter it plans to send to patients, the city defends its disclosure to USM, pointing to an exemption in the state’s HIV Confidentiality Law that allows such disclosures for research and program evaluation as long as the qualified researcher does not disclose the identities of the patients in any subsequent reports.

In this case, USM will provide the feedback received from the survey in a form that does not link it to individual patients.

Knowing and unknowing violations of HIPAA can come with civil and/or criminal penalties, according to the American Medical Association.

Ross Hickey, USM’s assistant provost for research, said the university initially received the list of patient names and contact information from the city with the understanding that the patients had authorized the city to release that information. Later, the city asked the university to enter into a business associate agreement, which is one of the ways HIPAA allows health information to be shared legally without a patient’s permission, he said.

Hickey stressed that the agreement did not change the way USM handled the information. He said the university’s institutional review board had already established strict protocols for protecting patient privacy before receiving anything from the city.

“We make sure it’s secure and that it’s confidential,” Hickey said. “That’s our focus – making sure that once the data has been handed off to us from the city we do nothing that would cause a breach of confidentiality.”

After receiving the complaints from patients, the city said it suspended the survey and conducted an investigation.

In addition to nine existing safeguards, the city then revised its agreement with USM to further increase patient protections. USM researchers put in writing that only two individuals would have access to the patient’s names and contact information; that such information had not been used improperly; and that it would not be shared in a manner that would violate HIPAA, among other things.

RESPONSIBLE USE OF DIAGNOSIS DATA

Michael F. Arrigo, a California-based expert who provides testimony on HIPAA-related issues, said he would be interested to see the documented policies and procedures that were signed by the patients before saying whether the city violated patient rights. He noted that damages have been awarded for improper disclosures of sexually transmitted diseases, but the law does allow for such information to be shared under some circumstances.

“I would want assurances that if my diagnosis information is out there it was being used responsibly,” he said.

In its letter to patients, the city conceded that it should have done a better job of informing former patients of the survey.

“First and foremost, we deeply regret that the city did not do a better job of communicating with (India Street Health Clinic’s) patients about the survey and explaining that USM was conducting the survey on behalf of the (city),” the letter states. “Although the survey was requested by and developed in cooperation with the patient advocacy committee … we also recognize that we should have notified all patients in advance.”

https://cloudup.com/cNeeS1MDI8d

Randy Billings can be contacted at 791-6346 or at:

rbillings@pressherald.com

Twitter: randybillings

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.